The Letter and the Spirit: The Wonder Rabbi

In a special edition of The Letter and the Spirit, we present a letter in honor of Yud Shvat:

By Anonymous, with the Rebbe’s notations

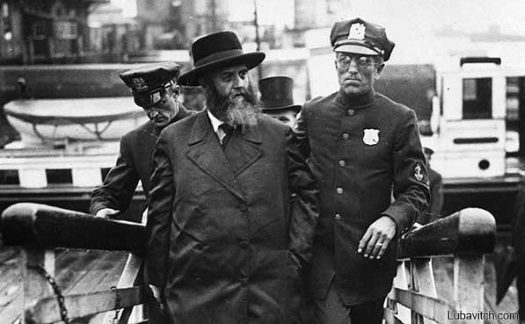

On March 19, 1940 I saw him the first time when they carried him down the special landing bridge off the S.S. Drottningholm, to the cheers of a huge crowd of followers and curious spectators and the flashes of press cameras.

I had heard of wonder rabbis and the adoration and absolute obedience which they command of their followers. But I had never seen one. It was therefore with a great deal of curiosity and skepticism that I had joined the hundreds of men and women from all walks and paths of Jewish New York who had responded to the notice of the arrival of the famous “Lubavitzer Rebbe” after his escape from the hell of occupied Warsaw. Young and old, rich and poor, bearing the traditional kaftans, black hats, beards and peyes or the most elaborate creations of Parisian couturiers or their Fifth Avenue competitors, they pushed and jostled each other to get closer and have a look at the man in the round fur hat with the reddish grey, long beard and the deepest fiery eyes who was slowly transported to the pier to be greeted by a galaxy of senators, congressmen, judges and civic leaders. His very presence seemed to electrify the large crowd and some of their feverish excitement penetrated my shell of skepticism. But as I walked away, I shrugged off the experience as an interesting instance of mass psychosis of faith, fame and curiosity. A few months from now, I thought to myself, after the novelty has worn off and the curiosity been stilled, this rabbi too will be forgotten in the anonymity of the Eastside humdrum life that has swallowed hundreds of former celebrities from the Old World whose arrival in the United States had caused a quick flurry of excitement.

I was wrong. A few months ago, almost ten years to the day, I was again standing at the fringe of a huge crowd, many times larger than the one that had lined the pier and even more colorful and variegated. But there were no cheers, no pushing and jostling. There was only the mute grief, the incredulous hushed silence of people too shocked to grasp the realty of the moment. They almost seemed in a hurry to bury their dead leader on the dreary, drab Sunday morning of January 28, as they walked out of step, hundreds of men high, in thick clusters behind the car that carried the body of Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn, the Lubavitzer Rebbe, through the streets around his mansion in Brooklyn, that were lined by thousands of mourners and spectators. Towards noon the sun broke through the clouds and warmed up the frosty air and reflected from the shiny Buicks, Cadillacs and Packards, the rickety old Model T Fords, the long line of buses that carried the mourning towards the cemetery.

Again I walked away in silence, lonely with thoughts, trying to shake off the powerful emotions of the present. But this time the feelings of a deep, personal loss, of a tragedy only partially understood, persisted; for meanwhile I had become acquainted with some of the qualities of the man whom they were carrying to his eternal rest. Not that I had become a “Chasid”, a true and pious believer in the near-miraculous powers of the Rebbe and his teachings. The inherent skepticism of my education was too strong for that. Yet as I followed the bier from far, the realization suddenly overwhelmed me that I had come to think of him as one who can do the impossible, who with his inexhaustible optimism, courage and idealism had conquered the sluggish resistance of our negative culture. He had taught me and thousands of other people like myself to believe again in the truth of “where there is a will there is a way.”

His “Chasidim” swear to the truth of numerous miracles of foresight and insight he has performed before their eyes. Perhaps yes, perhaps no. I would not know. But there is no doubt in my mind that Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn, the half paralyzed Lubavitzer Rebbe , whom I had seen carried off the gangplank in an almost helpless physical state, has during the decade of his stay in this country achieved miracles of organization, social service and education. And something else I have seen for which the term miracle may be too small. I have watched innumerous people enter his office tense, worried and tortured by conflicts; and then I have seen them leave with a glow of inner happiness and ease, radiating the joy of an extraordinary experience. I don’t know whether the man with the deepest searching eyes to whom they presented their small and big problems had seen beyond the fogs and clouds of their difficulties. But he certainly must have had the capacity of probing their hearts and finding the kind of words and the type of answer that loosed their tightness and transformed it into the dynamic certainty of conquering all difficulties and problems. This key to people’s hearts, more than any other phase of the Lubavitzer Rebbe’s life and work, convinced me that the term “wonder Rabbi” which I had ridiculed in youthful disdain, had its own meaning and place in Twentieth Century civilization.

To understand the great love, respect and admiration which hundred thousands of Jews the world over had for Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn, it is necessary to know some of the facts of his life and his achievements in all fields of Jewish endeavor.

Rabbi Schneersohn was born in the small town of Lubavitz, in Russia, on the twelfth of Tammuz 5640 (1880) as the scion of the famous “Schneersohn” dynasty that goes back to the so-called “Alter Rav”, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Ladi. This profound thinker and scholar, a disciple of the Maggid of Mezritsh, created the Chassidic ideology of “Chabad” which represents the initials of “Chochmah” – wisdom, “Binah” – understanding, and “Daath” – knowledge, in his authoritative treatise “Likutei Eimorim”, better known as the “Sefer Ha’Tanya”. Like this famous progenitor who was the official spokesman of the Chasidic movement in the controversy with the Gaon of Vilna and who commanded great respect even at the czarist court in Petersburg when he helped the Russian cause against Napoleon, the young Joseph Isaac was destined to play a major role in Jewish communal and religious life. As a small child he was already initiated into the whirlpool of activities concentrating in and about the “court” of the Lubavitzer Rebbe. For his father, Rabbi Sholom Dovber Schneersohn, himself a man of extraordinary scholarship and communal leadership, was determined to mold his son from the cradle on to the role which the spiritual leader of a worldwide movement like Chabad has to fit. By the time the boy had reached his fifteenth birthday, his father appointed him his personal secretary, thus placing him in a strategic post from where he was able to gain intimate knowledge and acquaintance with all the phases of the religio-political and religio-philosophical currents passing or emanating from Lubavitz. Not only did many of the great scholars of those days visit Rabbi Sholom Dovber to consult him on research problems or on matters of public Jewish concern, but frequently the Lubavitzer Rebbe was invited to attend the rabbinical conferences and the emergency sessions of the Jewish political and communal leaders every time one of the frequent crisis in the Pale of the Jewish Settlement arose. For besides his qualities as a leader, few Jews had such good standing at the court of Russia as the Lubavitzer Rebbe, ever since Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Ladi, in recognition of his valuable services to the country, had been given the status of a privileged citizen for himself and for all his descendents. And wherever Rabbi Sholom Dovber went, his young son came along, gaining valuable experience and insight into the forces and problems of the Jewish situation in those days of economic and political oppression.

Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn’s marriage to a relative, Nechamah Dinah, the daughter of the prominent scholar Rabbi Abraham Schneersohn, when he was seventeen years old, marked not only a week of joyous celebration for the followers of Chabad Chasidim, but it was the occasion on which Rabbi Sholom Dovber announced the founding of the first Lubavitzer Yeshivah, named “Tomchei Tmimim,” which was to set the pattern for numerous similar institutions the Jewish world over. For in its curriculum Tomchei Tmimim Yeshivoth attempted to combine Talmudic scholarship with intense study of the Chassidic literature and way of life. Thus it represented the culmination of the Chabad ideology which disavows exclusive concentration on Talmudics, like the “Mithnagdim”, as well as on “Chasiduth” like most other Chasidic schools. One year afterwards, at the age of eighteen, Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn took over the direction of the Tomchei Tmimim Yeshivah and under his guiding hand it flourished and grew from a single institution to a large net of similar schools all over Eastern Europe, moving its center and new areas of concentration to every country where Rabbi Joseph Isaac resided subsequently to his departure from Russia. And it was in this realm of establishing Yeshivoth for boys and girls that Rabbi Schneersohn scored his greatest successes and spent his best efforts. For, time and again, he expressed the thought that the spreading of Torah was the supreme task of the time, to which everything else was secondary. In America too, the last station of his pilgrimage through the centers of the Jewish world, Rabbi Schneersohn achieved the highest and most impressive results in this vital yet greatly neglected field, by starting undauntedly where others feared to tread.

Another phase of his work that Rabbi Sholom Dovber entrusted very early into the hands of his eminently capable son was the field of diplomatic missions. For strange as it may seem to the outsider, the court of Lubavitz was not merely the seat and center of Chasdic and religious activities, but it played an important role in the political affairs of the Jewish world, particularly of the millions in the Pale of the Settlement. At the age of twenty two Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn undertook the first of his numerous trips to St. Petersburg to intervene with the government on behalf of his Jewish brethren who were plagued with legal and illegal restrictions by major and minor officials in the various regions of the empire. His intelligent and polite, yet clear and firm conduct of the negotiations, won him the favor of the highest circles at court, in St. Petersburg, as well as in Moscow, and slated him for the role of spokesman of the Jewish people in his and other countries. He was only twenty five years old when his experience in dealing with diplomats and princes was called upon to ease the terrible plight of the Jews in the wake of the October Revolution in 1905, when government inspired pogroms plagued the Jewish community, as a diversion of the popular attention from the defeat in the Russo-Japanese War and the ensuing unrest and rebellion against the hardships of the Czarist oppression. It took a great deal of courage, care and skill on the part of the young man, to leave the country, establish relations with the most influential statesmen of those days in Germany and Holland and to induce them to intervene on behalf of the suffering Jews of Russia. Successful far beyond expectation, the young Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn returned to Russia as a hero of his people who appreciated his help and offered him their love and admiration to a degree rare for a young man his age.

Naturally, this mission earned him little favor in the eyes of the Russian government who had begun to be annoyed by the constant interference of the young rabbi from Lubavitz with their economic or political restrictions of the Jews. Even his status as a privileged citizen did not help him long, as he kept on commuting between his residence and the seats of the local and national governments in his efforts to avert trouble and prevent further decline of the already low economic state of the Jewish population and the ensuing moral depression. In due time his courageous standing up to the Russian officialdom caused him to be thrown into one prison after the other, never holding him long and never frightening him from doing exactly the same thing time and again whenever the need arose. Official inquiries were never able to find anything criminal against him and instead of a mark of shame, every case of imprisonment, particularly during the years from 1902 to 1911, turned into another personal triumph which increased the love of the Jewish people in Russia for this fearless young protagonist of their plight.

There were other ways in which Rabbi Joseph I Schneersohn from his early youth on engaged in easing the economic pressure lying heavily upon the impoverished Jews of Russia. His illustrious forebears, beginning with the founder of the dynasty, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Ladi, had already realized that one form of escape from the constantly increasing economic ruin and the ensuing demoralization was the creation of concentrated, economically independent settlements. After the Rav’s death, his son was granted a large strip of land around the city of Kherson by the Czar who wanted to show his gratitude to the family of Rabbi Schneur Zalman and agreed to help the project of Jewish settlements. To many thousands of Jewish families the Kherson colony meant physical as well as spiritual salvation and it set the pattern for others to follow the road to the land. The grandson of Rabbi Schneur Zalman, known as the “Tzemach Tzedek”, from the title of his many-volumed collection of Talmudic and Halachic responsa, continued the work of his father by establishing an even larger colony of settlements around the city of Shtzedrin. Each Lubavitzer Rebbe in his turn continued this important trend away from the “luft-existence” of the East European Jewish masses and by stressing the idea of agricultural colonization as a suitable occupation helped transvaluate the pattern of popular depreciation of manual work.

Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn did not only further propagate the establishment of agricultural Jewish centers which served not only to provide economic security, but represented the strongest concentration of Jewish religious and communal activity. He promoted the idea of Jews learning skilled trades, in the face of the low self esteem in which the “baal melochoh” was held in Eastern Europe. This social upgrading of the farmer and the craftsman paid rich dividends not only in those days of economic exigency, but later on when the Soviet regime superseded the Czar yet continued the imperial policy of oppression of the Jews under the pretense of eliminating the unproductive elements of the masses of Jewish dealers and businessmen. In addition to establishing farming and craft centers, Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn was also leading the movement to establish independent orthodox Jewish industrial centers, factories where Jews worked in all phases of the productive process and acquired skills that became equally precious during the Soviet oppression, as the agricultural and craft training. The industrial center of Dubrovna, which Rabbi Joseph Isaac had helped organize as a young man, alone had enabled many thousands of Jews to survive. Thus the Chasidic ideology which does not recognize the exclusive intellectual religiosity of the Mithnagdic philosophy bore rich fruit in the work of the Lubavitzer Rebbe when he promoted the shifting of the masses of his Chasidim to the various forms of manual labor, over and against the popular deprecation of such professions for an orthodox Jew.

In 1920 Rabbi Joseph I Schneersohn was called upon to become the official head of world movement of Chabad, after the death of his father Rabbi Sholom Dovber. Russia was in turmoil. Defeat in war, revolution, unrest, insecurity and utter demoralization had wrought havoc with the very foundations of peaceful life for the Jews even more than for the rest of the population. In this terror-fraught situation Rabbi Schneersohn, the new Lubavitizer Rebbe, was faced with the double task of securing a minimum basis of economic and spiritual survival for the distressed Jewish orthodox masses. It was here that the agricultural and industrial training proved to be of great value. For it enabled all those who had engaged in it to retain relative independence and more than that it gave them the chance to live together in concentrated areas, thus assuring them of a maximum of inner strength and power of resistance against the violent attacks on their soul from the Soviets, led by the ominous Yevsektzia, the anti-Jewish Jewish section.

Undaunted by the terror methods of these enemies of the Jewish religion Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn fought almost single-handed against the catastrophic secularization of the largest reservoir of the world’s Jewish community. Openly and secretly he defied death and severe punishment innumerous times, organizing schools, yeshivoth, congregations, services, meetings and study groups under the very nose of the suspicious officials. Unable to stay long at one city, he moved his residence impromptually, travelled extensively giving courage and inspiration to the small and large groups who did not yield to the pressure from the outside. His students and disciples followed his example and risked their lives visiting the near and far Jewish communities teaching, organizing classes and services and strengthening the general resistance. Economically too, Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn organized financial help for the small craftsmen and artisans, enabling them to refrain from work on Shabbath, and support the rabbis and communities who would have perished without subsidy

Naturally the renegade officials of the Yevsektzia were not willing to put up with this “counterrevolution” of the Lubavitzer Rebbe and they used the full arsenal of their notorious methods of intimidation and terror to change his mind. But their worst and vilest forms of torture left the determined rabbi unimpressed. Even when they set the gun on his breast, he stated calmly that he would not give up his G-d. “I have only one G-d and two worlds. Your little toy here does not frighten me.”

By 1927, after seven years of bitter struggle, Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn was thrown into Spalerno Prison of Leningrad, from which few return. Only the intervention of international statesmen saved the Lubavitzer Rebbe, after the death sentence had already been passed. Subsequently he spent some time in exile in Kostroma near the Ural Mountains, until continued pressure from America and other countries effected his release and eventual permission to leave Russia with his family and his priceless library of Chasidic and general Hebrew literature.

Despite these years of harrowing experience Rabbi Schneersohn did not pause to rest. At once he set out to help Jews who were forced to remain in Russia. Taking his residence to Riga, Latvia, he sent matzoth and other religious articles to his brethren in his former homeland and his emissaries traveled back and forth giving the spiritual encouragement so vitally needed. A trip in 1930 to America and a visit at the White House and the Holy Land brought not only huge throngs of Chasidim and admirers to greet him, but enabled him to organize his relief and educational campaigns for East European Jews on a world-wide basis. Despite the fact that his and his disciples’ work in Russia had maintained a good deal of orthodox Jewish life, there was no doubt that Russia, once the life center of orthodox Judaism, had lost its primary role. Thus after his return, the Lubavitzer Rebbe established “Tomchei Tmimim” Yeshivoth in Poland. His residence in Otwock, near Warsaw became the world center of Chabad Chasidim and a beehive of communal and religious activities spanning the Jewish orbit

The Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939 stared a new phase of heroism and suffering on the part of the Lubavitzer Rebbe who refused to flee in time, despite the urging of his followers the world over. Fearlessly he faced bombings and death, sitting in a Succah, giving inspiration and the will to survive to the thousands of Jews in Warsaw. Only after he had saved as many of his students and followers as possible and after there was no longer any chance for effective aid, did he allow himself to be taken out of the hell of Poland, to the security of America from where he hoped to be of much greater service to his suffering brethren.

It would not have been like the Lubavitzer Rebbe to start on new phase of his life without setting his sight for a new goal and the new situation into which Providence had placed him. In his response to the greetings of the numerous organizations and representatives of governmental agencies at the pier ten years ago, he said that whatever the L-rd would grant him yet, would be dedicated to “Hatzlath Yisrael” and “Harvatazth Torah” to relief for the suffering Jewish people and to the spread of Torah among the youth of America and other countries.

Though worn out and of broken health from the years of bitter struggle, imprisonment and incessant battle on the bastions of Judaism, the Lubavitzer Rebbe set about fulfilling this program from the very first day after his arrival. Like a clarion call in a sleeping castle his proclamation to save the Jewish youth in this country, in the cities and towns and villages where the Jewish religion was a memory of a past generation, met with indifference, startled disbelief, curiosity and ridicule. Jewish education had reached a low and the existing institutions of Torah learning struggled valiantly for their survival. Yet undaunted by mockery, lack of interest and seemingly insurmountable difficulties, Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn kept not only calling and shaking the sleeping conscience of the responsible Jewish public to awareness of the spiritual plight of the Jewish youth that was searching for an answer and guiding light, torn by the disillusionment of valueless self-contradictory ideologies and isms. Only a few weeks after he had begun his sojourn in this country he and set up organizations to carry his may pronged attack onto the Jewish street, the Jewish home and the Jewish school.

His first step was the establishment of a central Yeshivah Tomchei Tmimim that was to become the mother institute for a whole net of Yeshivoth for boys and schools for girls and that was to produce teams of qualified teachers and inspired community workers, rabbis and youth leaders who translated the plans of Rabbi Schneersohn into reality. An organization called “Machne Israel” was to engage in all activities that might in any way strengthen the forces of orthodox Judaism in this country and the world over, providing guidance services and functionaries to outlying communities, supplying religious article, literature and if necessary, financial support.

A special department of Machneh Israel, for example, concentrated exclusively on visiting Jewish farmers throughout the states of the East Coast and New England. Isolated from contact with the Jewish world, these lonely Jews, frequently hundreds of miles from the nearest Jewish community, had lost much of their Jewish faith and religiosity. Whatever their background and training, in the decades of living among non-Jewish farmers or all to themselves they had abandoned or forgotten what they had learned in their youth and their children were far from getting even a minimum of Jewish education. If it were only that the representatives of the Lubavitzer Rebbe spent time on paying visits to these isolated Jews, if they did no more than speaking to them and making them realize that they were not alone, that someone cared what happened to them, Machneh Israel would have served a vital function. But far beyond that the emissaries of Rabbi Schneersohn provided the farmers with religious article, with tefillin, siddurim, chumashim and whatever else they lacked. They arranged for kosher food, for regular visits from rabbis and teachers, for regional gatherings and other forms of inspiration and practical help. Mobile synagogues and kosher kitchens, records and special radio programs are among the projects of the Farmers Division of Machneh Israel.

On a national and international basis the same type of work carried on by the Farmers Division, reached many thousands of Jews in all corners of the world who turned to 770 Eastern Parkway, the residence and center of the Lubavitzer Rebbe’s activities, for advice and help. During and after the war many new centers of Jewish life had sprung up in places and countries that had little or no Jewish tradition that lacked the fundamentals of Jewish life. Machneh Israel was instrumental in providing them with the religious articles, books, Sifrei Troah, shofrot, megilloth, matzoth and wherever possible, with personnel to serve their religious needs and functions.

More astounding yet and of almost revolutionary character are the achievements of the other mighty prong of Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn’s assault on the Jewish scene, the “Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch “, Central Bureau of Jewish Education. Not colored by any party affiliation, not even by bearing any specific relation to the Chabad Chasidic ideology, this organization has made all those things come true which the skeptics declared impossible when the Lubavitzer Rebbe proclaimed his program of activation the Jewish youth on a large scale. It is not enough to state here that during the ten years of its existence the Merkos has published and distributed over two million books; that it has organized thousands of boys and girls in yehsivoth, Hebrew Day Schools in large and small towns; that it has established hundreds of clubs in neighborhoods and sections where yiddishkeit seemed to have lost its very last foothold. That it has sent its workers into camps and centers of post-war Europe to do the same work for the remnants of the once proudest and best centers of Jewish life.

To really appreciate what the Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch has done one has only to consider the background and achievements of its publications department. Anyone acquainted with the state of Jewish juvenile literature ten years ago, anyone who has ever had a look at the antiquated, ridiculous, impossible type of textbooks used in Talmud Torahs and Yeshivoth then; anyone who has ever seen and felt the big empty yawn in the shelves of a Jewish library where fiction for children was supposed to be, will realize the magnitude of this phase of the work of the Merkos, both in the field of nonfiction and fiction. Only one not knowing the approach of the Lubavitzer Rebbe will question his concentration on the apparently secondary field in Jewish education. For, if there was one basic principle in this work of Rabbi Schneersohn, it was the idea that every method that could possibly help to bring Torah and Yiddishkeit closer to Jewish youth, had to be used. Preaching and teaching, he argued, were of little value if the rest of the intellectual life of a child was filled with ideas and views that contradicted the content of the preaching. Everything – textbooks, fiction, magazines, even comics – whatever the other world used to lure the Jewish child away from the Jewish heritage, has to be drawn into service. From this perspective the Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch set out to create the basic tools of Jewish education which won it fame and recognition far beyond the orthodox Jewish circles.

From the first month of its existence it began to publish a monthly magazine in English called “The Talks and Tales” and a magazine “Shmuessen Mit Kinder un Yunget” in Yiddish. Through the years it has not missed a single month putting out the pink and blue companion magazines and sending them out in ever increasing numbers to all cities, towns and hamlets where Jewish children might want to read Jewish stories, poems, curious facts and dates about Jewish heroes, books, holidays and feasts. In some Jewish schools these magazines have become obligatory reading because the teachers have found them most valuable tools of informal instruction. Bound volumes are sold to youth leaders, to parents and young people who treasure their rich store of fine and interesting material for every Jewish occasion.

Of even greater importance was the immediately started campaign to create new, updated in form and content, textbooks in every vital field of Jewish teaching. Under the surveillance of the Lubavitzer Rebbe himself, teams of experts collaborated to produce, for instance, a history book for the Jewish home and school that covers every phase of the Jewish past, form the creation to the present, called “Our People.” The three volumes that have appeared thus far in print have evoked a great deal of praise and enthusiastic response from teachers, parents and group workers for their attractive form and well-structured organization of the material based exclusively on the authentic, traditional sources. Of equal importance are the five volume series of a Hebrew textbook, called “Unser Buch” which teaches not only the fundamentals of the Yiddish language, but combines it with reading in “Yahaduth,” in selections that from the very first page on convey the spirit of Jewish tradition and culture, rather than empty, meaningless phrases, sentences and paragraphs.

This holds true for the many other textbooks created by the Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch for special purposes and topics, at the initiative and direction of Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn. It is never merely a subject that is taught or a topic that is in the large or small books presented; but the full, rich background of Jewish culture is added to give the child the feeling of the total, the whole picture from which the topic is merely a segment holding promise of more and richer reward.

In this connection, one thinks of such popular publications as “The Shaloh” books for young children and “The Complete Festival Series.” They cover every aspect of each major Jewish holiday in an interesting, well illustrated booklet. In them one realizes the value of this work of the Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch for Jewish education in this country, where the dirth of the most basic teaching aids had hampered and blocked progress almost to the point of retrogression, until such men as the Lubavitzer Rebbe wrought a revolution, disregarding the difficulties and cost of publishing.

More surprisingly yet than the textbook library created by the Lubavitzer Rebbe, is the rich shelf of fiction for juveniles in English written or translated under his direction. Anyone acquainted with the prohibitive cost of printing will appreciate the fact that in a field where the Jewish child was almost completely dependent upon the rather thin or even bad fare offered by non-Jewish juvenile literature or by thos whom the rich Jewish heritage is a source of mockery and ridicule, the Merkos had ventured to produce good, solid books of lasting value. There is the series of classics by Dr. Lehman, there are plays, collections of short stories, novels and novelettes covering most phases of historical and modern Jewish life.

This publications division of the Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch is only one of the many revolutionary ways in which Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn had broken a path that was later on followed by other educational organizations, much to his satisfaction. For this was what he had set out to accomplish, to arouse the responsible Jewish bodies, the leaders and organizations, to their task of saving the hundreds and thousands of Jewish boys and girls who were going lost to the Jewish religion and the Jewish people because there was no one to answer their call for help and guidance.

And then there is of course the one side of Rabbi Joseph ai. Schneersohn which may perhaps not have come into the public eye as much as his religio-political and his communal or educational activities, his work as a scholar and spiritual leader of the world Chabad movement. It seems rather impossible that a man who had never known a day of private life, who had been embroiled in the most difficult, most enervating and complicated, bitterly fought battles for Judaism, should yet have found time to study and to produce such a multitude of profound works, covering many phases of the Chasidic philosophy, of general Jewish theology, of “Mussar”, Hebrew and Yiddish literature and of running commentary to the event of the day. Yet by the time he passed away, Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn had published a multitude of brochures and books, many of them of major proportion that would have represented the harvest of a life time in the case of a man of lesser stature, not born to the pen. Only a person well versed in the terminology of Chasiduth can fully appreciate the contents of his thirty two “Likutei Diburim”, collections of speeches addressed to his followers, of his eighty “Kuntreisim”, his commentaries to extant works of the Chasidic literature, his “Sefer Hamaamorim”, many volumes of dissertations on special topics of Tamudic or Chasidic nature, his “Sefer Hasichoth”, his “Sefer Hamichtovim” and his “Sefer Hazichronoth”, of which only parts are as yet published. 1. Only after the hundreds of manuscripts found in his files of essays, commentary, novella etc. will have been printed will his full stature as a scholar and writer be as apparent as the part he played in public as a leader and guide of human beings and of the Jewish community who woes him such a vast debt.

Of all these facets of a monumental personality I thought when I walked away from the funeral of the late lubavitzer Rebbe.

I had only been privileged to look at him from far and to feel the impact of his overwhelming stature as a giant of the spirit and action. Yet I realize that to the thousands of rich and poor, old and young, and to the many more thousands who were not able to participate in the burial of the earthly remains of Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn, he must have represented that which the word “wonder Rabbi” or better, “Rebbe” in the true Chassidic tradition, means in our age of atomic fission.

________________

- The index of his books and ma’amorim which I am preparing is approximately 100 pages. (Rebbe)

tysm for posting

:-)