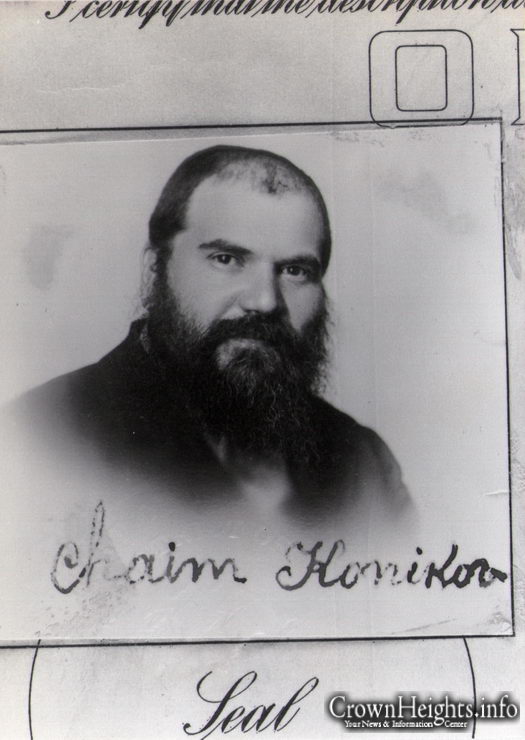

Our Heroes: Reb Chaim Zvi Hirsch Konikov

Reb Chaim Zvi Hirsch Konikov was born in 1897 is a small town in Russia * He was an adherent follower of the Frierdiker Rebbe, and witnesses many miracles while living in Czarist and communist Russia which saved his life on many occasions * Arriving in New York with his family in 1929, he was one of the founding members of the Chabad community in the U.S. * He passed away on 24 Tammuz, 1956.

My Zeide, Reb Chaim Zvi Hirsch Konikov of blessed memory was born in Petrovitch, Russia, in the year 5657 (1897), to Zev and Leah Konikov.

By the time Chaim Zvi was 16 years old, he was already called an Iluy, given the title “Yored l’umkei shel Halochoh,” one who has delved into the depths of Halachah, and appointed Shoel Umaishiv (one who responds to questions) for boys his own age and older.

As he grew older, he practiced shmiras haloshon as taught by the Chofetz Chaim, Reb Yisroel Meir of Radin. Ironically, it was loshon horah which would change the course of young Chaim Zvi’s life forever. While learning in yeshiva, he heard some of his fellow bochurim heaping abuse upon Lubavitcher Chassidim. In vain, he waited for somebody to stop them. However, the loshon horah con-tinued unabated. The students seemed to feel that when denigrating Lubavitcher Chassidim based on hearsay, they were exempt from the laws of loshon horah. It was then that the young Chaim Zvi decided to go and observe for himself the lifestyle and attitudes of this much maligned group.

Chaim Zvi eagerly awaited his first glimpse of the Rebbe Rashab. Would he stride into shul masterfully, like royalty, as befits a Talmid Chochom, a Rebbe with so many followers?

No, there was no air of self-importance at all as the Rebbe entered the room on Friday night to say a maamar for the Chassidim. The Rebbe seemed completely unaware of the honor and respect that he was being accorded by the Chassidim. His attitude indicated that all this was not for him personally. ‘I his conquered the bochur Chaim Zvi’s heart. Then and there, he decided to plant his roots deep in the nurturing soil of Lubavitch.

He wrote to his family in glowing terms that he was going to stay in Lubavitch, with the words, “A new world has opened up before me.”

He had a strong connection with the Rebbe Rashab’s son and the Lubavitcher rosh yeshivah, Reb Yosef Yitzchok (Rayatz), who would later become the Rebbe Rayatz, or Frierdiker Rebbe. This close connection would continue throughout their lives.

On the first night of Pesach in that year, Chaim Zvi sat down to the Seder in Yeshivas Tomchei Temimim wrapped in a white kittel according to the minhag of the misnagdim. He was the only one dressed this way, but he did not mind, as this was still his custom. The Rebbe Rashab came in, together with the Rayatz, to see the bochurim before going to his own seder. He saw Chaim Zvi sitting in his kittel, and commented to the Rayatz, “Er main! dos mit ahn emes un mit tmimus.”

After that year, he began following Lubavitcher min-hagim, and ceased wearing a kittel to the sedorim.

The Rayatz invited the bochur Chaim Zvi to live in his own apartment, which was on the same floor as that of the Rebbe Rashab. Fully aware of the honor which had been bestowed upon him, the young Chaim Zvi tried very hard not to disturb the privacy of the Rebbe’s family.

The Rayatz got to know Chaim Zvi, and trusted him to such a degree that before leaving on a trip, he showed his young houseguest a hidden button behind a picture hang-ing on the wall. This button opened the door to the secret path which led to the Rayatz’s secret library.

With the permission of the Rayatz, Chaim Zvi spent time in the library when the Rayatz was out of town. The Rayatz knew he could trust Chaim Zvi not to remove any seforim from there.

In the library, he once noticed a half-smoked cigarette of the Rayatz. Chaim Zvi lit it and took a puff. Many decades later, after the Rayatz became the Rebbe, he told his son Velvel that he deeply regretted doing so, feeling that it was not right that he had touched the Rebbe’s cigarette.

His nickname in Lubavitch was “the second Baal Ha-turim.” Every time someone came to Lubavitch he would give the newcomer a gematria for his name, a practice used by the Baal Haturim.

The time arrived for Chaim Zvi to be drafted into the Russian army.

Chaim Zvi went to the Rebbe Rashab, who assured him, “Du vest nit dinen.” (You will not serve.)

Evading the draft was a serious crime, so, now in fear for his life, he fled to the shul and did not leave it. He re-mained there, studying every single sefer there, for about 6 months.

A Lubavitcher Chossid saw Chaim Zvi hiding in the shul, and reported this to the Rebbe Rashab. The Rashab replied, “Ich hob doch em gezogt er vet nit dinen!” A misnagid also saw the bochur hiding in the shul, and, knowing that the Chofetz Chaim liked him very much, he reported to the Chofetz Chaim that this bochur was hiding in the shul. The Chofetz Chaim replied, “Er hot doch a brochoh fun de Lubavitcher Rebbe!”

That very year, the Czar passed away and all political wrongdoers, including Chaim Zvi, were pardoned for their crimes! He could go home.

However, he was still required to report for the draft. His father advised him to attach a false cataract to his eye in order to obtain an ex-emption from military service.

It was with a heavy heart that he traveled to Moscow by train, with his battalion, for the physical exam. What if the doctors saw through his ruse? He could be severely punished for trying to avoid serving in the Russian army. As he traveled, his fears about his future gave way to more pressing worries. Shabbos was fast approaching and the train showed no sign of arriving in Moscow in time.

He turned to the Jewish captain of the battalion, and said, “It’s Friday afternoon. I have never traveled on Shahbos. I am leaving:’ The captain tried to convince him to stay, saying, ”This is a matter of life and death! Leaving the train when you were expressly ordered to stay with the army could easily earn you the death penalty. You will be a deserter!“

But the train had stopped, so Chaim Zvi got off and went into the nearby village in search of a shul in which to daven Kabbolas Shabbos.

Right after Havdoloh, he decided to retrace his steps to the place where he had left the train on Erev Shabbos. He was shocked to see a train, the same train, standing in the same place! The Jewish captain pulled him onto the train at the last second, just as it pulled away, and breathlessly informed the young Chaim Zvi that a technical glitch in the train’s engine had disabled the train on Friday after-noon, and only now was the mechanic’s work finished! The captain was amazed by the miracle that had happened to this bochur.

In Moscow, there was a long line in the hall where the recruits were being given their eye examinations. Chaim Zvi listened fearfully as the doctors examined the boys ahead of him.

”Fake! Next!“

”Fake! Next!“

At last, Chaim Zvi’s turn arrived and he stood opposite the doctor. The doctor whispered to him, ”Fake, but I’ll do you a favor and write here that you have an illness that will make you exempt forever.“ And the doctor handed him an exemption slip.

The bochur who would later become my zaide grew up and continued to face danger. But miracle followed miracle and my zaide was rescued, time after time.

The Communists often harassed the religious Jews of Russia. Once, Reb Chaim Zvi was traveling with a group of Lubavitchers including the Rashag (Reb Shmaryahu Gurary, son-in-law of the Frierdiker Rebbe), bringing a large sum of money that had been raised for Yeshivas Tomchei Temimim to the Rebbe Rashab. They slept in an empty cottage on their way back to the Rebbe. Suddenly, two Communists burst into the cottage, bran-dishing weapons. Everyone else had run out, but Reb Chaim Zvi had not heard the warning shouts. One Communist pointed a dagger at my zaide and demanded the money, but he refused to show them where it was hidden. The Communist stabbed my zaide repeatedly, torturing him to force him to give it up, but he would not. My zaide pulled the dagger out of his body and used it to fight the other Communist, who was holding a gun. The now-unarmed Communist ran out, and the other soon followed. The money was delivered safely to the Rebbe Rashab.

The Communists enacted a law which forbade anyone to take wine from city to city. However, this did not deter Reb Chaim Zvi. He was going home for Shabbos, wine is needed for Kiddush, so he took wine with him.

He was caught by a policeman, and thrown in with a group of criminals who were about to be shot by a firing squad.

Suddenly, a high official came galloping by on horse-back. The high official stopped and looked at the group. He pointed to my zaide and shouted, ”You, go!“ and Reb Chaim Zvi ran for his life. (With the wine!)

One day when Reb Chaim Zvi was walking in the street, he realized that a big tall fellow, a Cossack, was following him. He ran down a side street but the Cossack pursued him. It was obvious that the Cossack was determined to harm the unarmed Jew. As the Cossack got closer to the Jew, a door opened and a goy stuck his head out and called–”Jhid! Quickly, come inside!“

Reb Chaim Zvi was pulled inside, and the door was quickly locked. Within seconds, the Cossack was banging on the door.

”What do you want?“ asked the homeowner.

”I want the Jhid,“ answered the Cossack.

The homeowner, a goy, called to his sons to bring glass bottles. They cracked the bottles, pushed my zaide aside, and opened the door, holding the broken bottles. ”Come on in!“ they encouraged the Cossack warmly.

They hit the Cossack on the head with the broken bottles until he was unconscious. ”Flee for your life,“ they urged Reb Chaim Zvi, ”We will deal with him:’

The miracles that Hashem performed for Reb Chaim Zvi were doubly miraculous in that the goyim put their own lives in danger to save him. It was tantamount to treason for the doctors to issue him an exemption from military service based on a non-existent illness. Cossacks were dangerous men with whom the local population usually made every effort to stay on good terms. However, Hashem in His mercy helped Reb Chaim Zvi each and every time.

In 1919, in Poltava, Russia, Reb Chaim Zvi Konikov married Bryna, the daughter of Reb Moshe Yitzchok and Miriam Bluma Slepak. Rabbi Yehuda Chitrik a“h, who passed away this year at the age of 106, was a Witness at their wedding.

As a married man, Reb Chaim Zvi served as a Roy in Smolensk, Russia, and in Kobilak, a town in the district of Poltava, Russia.

Fortunately, my zaide figured out a way to repair sewing machines without having the parts. In this way, he earned enough money to support his wife and family and was also able to give large sums of money to tzedokoh to help many needy Yidden.

One Jew was extremely jealous of his financial success. He threatened that if Reb Chaim Zvi would not accept him as a partner in the business, he would inform on him to the Communists. He made good on his evil threat, and four weeks later, the slanderer passed away. But, Reb Chaim Zvi remained on the blacklist.

Rebbetzin Bryna suffered greatly under the harsh rule of the Communists, who pursued her husband unremittingly. He often had to run away and always had to hide, and she yearned with all her heart and soul to leave Russia. Towards that goal, her brother, Reb Yerachmiel Slepak, who lived in America, sent them a package which contained a letter requesting that Reb Chaim Zvi come to the United States to serve as a rabbi for a specific shul in Newark. This would help them to get visas. He also sent money with which to purchase tickets for travel by ship to the U.S., for Reb Chaim Zvi, Rebbetzin Bryna, and their two children, Moshe Yitzchok and Devorah. (Their third child, Velvel, would be born later, in the U.S.)

Reb Chaim Zvi agreed that the time was right for them to leave the U.S.S.R. However, he needed a senior official to approve the cashing of his government stocks. Anyone with a record like Reb Chaim Zvi’s would be putting himself at grave risk by voluntarily walking into government offices. But what choice did he have? So, despite the obvious danger, Reb Chaim Zvi walked calmly into the official building in Moscow, secure in his emunoh that Hashern would help him now as he had in the past, though he was literally delivering himself into the hands of those who were after him.

Much to his surprise, the officer he needed to see held the door for him, gave him a chair, and accorded him much honor. Reb Chaim Zvi had a big black hat, a fur collar and a tall, proud demeanor, and so the officer mistook him for a high official from another country. He fulfilled every one of the Chossid’s requests, and when my zaide rose to leave, the officer also rose, and graciously asked him, ”Is Your Honor an Englishman?“

Reb Chaim Zvi could have answered in an evasive manner, but he would never deny his religion.

”No,“ replied Reb Chaim Zvi, and then in a voice that betrayed no hint of fear: ”I am a Jew.“ The officer’s face contorted with fury as he realized he had allowed himself to be fooled by appearances. He bellowed, ”GO!“ in a voice filled with rage. Reb Chaim Zvi didn’t wait to be told twice!

Finally, in 1929, the entire family had Yechidus with the Rebbe Rayatz, in Riga, and then they left for America, the land of freedom, on the majestic ship Ile de France. Most of the passengers were afflicted with seasickness, but Devorah, then three, greatly enjoyed the journey.

The family of four (Reb Chaim Zvi, Rebbetzin Bryna, and their children, Moshe Yitzchok and Devorah) arrived in the United States and settled in Newark, New Jersey, where Reb Chaim Zvi served as Rov for two years.

Then the Konikovs moved to Williamsburg, where my zaide became Rov of the Tzemach Tzedek shul in Williamsburg, after the passing of the previous Rov, Reb Yehuda Leib Lokshin. The Rebbe Rayatz wrote to the congregation, ”When the sun set, it rose again, with the appointment of our good friend HaRav HaGaon Reb Chaim Zvi sheyichyeh Konikov:’

But things in that shul were not smooth or simple. When Reb Chaim Zvi had difficulties in the Tzemach Tzedek shul (politics between high-ranking members, disagreements over policies, etc.), he would write to the Frierdiker Rebbe for guidance and encouragement. There is a wealth of letters that the Frierdiker Rebbe wrote to Reb Chaim Zvi on this and other topics, printed in the Igros of the Frierdiker Rebbe.

The closeness of the Rebbe Rayatz to his beloved Chossid was demonstrated again years later, when Reb Chaim’s Zvi’s siddur and machzor were found in the safe of the Rebbe’s library in 770.

In the 1940s, Devorah Konikov, then teaching Jewish children in Talmud Torah (after their regular day at public school), told her father that the priest was coming to public school once a week to take some of the children out of class, and talk with them about religion. The Konikovs asked the obvious question: “If the priest can do that for the Christian children, why can’t we do the same for the Jewish children?”

And so, with the help of several bochurim (including J.J. Hecht a“h, Herschel Fogelman yblc”t, and others), my zaide began to take Jewish children out of school every week. He brought them to shuls, where they were taught about their heritage, given prizes and treats, and brought closer to Yiddishkeit.

This program, first called Wednesday Hour, was later renamed Release Time. Reb Chaim Zvi would sign out about 200 children every week on his own responsibility, and arrange teachers for them.

In 1945, Reb Chaim Zvi wrote a letter to the Frierdiker Rebbe describing these activities, and the potential for growth. The letter was returned with a note on the bottom, through the Frierdiker Rebbe’s son-in-law, the future Rebbe: “Everything that is suggested in this letter should be carried out.” The Frierdiker Rebbe wholeheartedly approved of Release Time.

My zaide recommended that Rabbi J.J. Hecht, his most capable and dynamic bochur-teacher, take over and expand the program. And indeed, the Rebbe appointed Rabbi Hecht.

Reb Chaim Zvi also established five small after-school programs, in different areas in Brooklyn, for Jewish girls who were students in public schools, all called Bais Rivkah Schools. The Frierdiker Rebbe sent him $50 in order to be a partner with him in this endeavor.

Reb Chaim Zvi’s daughter, my dear aunt Devorah, worked faithfully at his side organizing all these programs. My father, Reb Moshe Yitzchok Konikov, then a teenager, was very active, too. Together they would make their way to the different shuls and would hold Mesibos Shabbos for the children on Shabbos afternoons. Father and son compiled a Yiddish song book, including some sweet original songs, to encourage Jewish children to say brochos. My father would give the children sweets to eat and different kinds of besomim to smell, so that they could recite several different brochos, and also say amen after hearing the brochos of others.

One Yom Kippur (in the 1940’s) when my zaide was ill, the Frierdiker Rebbe was crying under his talks (before Kol Nidrei): “MEIN Chaim Zvi zol hoben a Refuoh Shleimoh b’ramach eivorov veshasah gidov.” (MY Chaim Zvi should have a complete recovery in his entire body.)

The Frierdiker Rebbe’s heartfelt words were overheard by Rabbi Chaim Moshe Yehoshua Schneersohn, ben achar ben (a direct descendent) from the Alter Rebbe, who lived on Eastern Parkway at the time. He went and told this to my zaide, who excitedly jumped out of his bed and said, “Ich bin shoin gezunt!” (I am already well!)

Reb Chaim Zvi wanted his son Velvel to learn all the time. As a young boy, Velvel sometimes wanted to go and play with his friends, but he didn’t dare ask his father’s permission. While it was difficult to be the young, American-style son of such a spiritual, European-style man, it was also a gift. Velvel recalls that he was an ardent baseball fan as a young boy, but would never, ever listen to a baseball game while his father was at home. He would not dare to upset his fa-ther. So Velvet would wait until his father was busy with something else or out of the house, then he would sneak into the kitchen and turn on the radio for a few seconds, on the lowest possible volume, until he heard, “Dodgers are winning, 10 to 6—” and then he would quickly shut it off. If the young Velvel was playing handball outside, and his father came out of the house, Velvel would not continue playing, or call out, “I’m coming in a minute!” or “It’s almost over!” Velvel would drop the game instantly and run to his father’s side. All the other kids would whisper, “His father is here:’ in awe.

Velvel was a star at sports, especially handball. At eight years old, he would play against boys five years older than himself, and would win. He often played in front of a large, admiring audience. However, if his father appeared, he left the game immediately.

Many people who saw him play wanted him to enter handball tournaments. Though Velvel would have enjoyed playing in a tournament, he didn’t even think to ask his father’s permission. He knew the pain even hearing such a question from him would cause his father.

”Ess iz gut far gezunt, m’dahrf shpilen, ober tzu fil is aim avodah zoroh,“ Reb Chaim Zvi would tell Velvel. (”It is healthy to play, but too much is idolatry“)

Sometimes Velvel would ask his father to take him somewhere; for example, on a boat ride. Reb Chaim Zvi would reply, ”And what will the Aibershter gain if we go?“ He did take walks with his son, conversing on the way. While they walked, he often asked Velvel, ”Voss trachstu?“ He wanted his son to think thoughts of Torah.

Every year Reb Chaim Zvi would lovingly present to the Rebbe, in a white handkerchief, a modest sum of money from his own earnings to be used for maamud.

The Frierdiker Rebbe once exclaimed (regarding his dear Chossid’s maamud money): ”Chaim Zvi’s fuftzik cent iz by mir vert tyerer vi hundreter fun andere!“ (Chaim Zvi’s fifty cents is worth more to me than hundreds from others.)

In the very last Yechidus (of many) that Reb Chaim Zvi had with the Frierdiker Rebbe, the Rebbe extended his hand to him. A Chossid and Rebbe traditionally do not shake hands. Not knowing what to do, Reb Chaim Zvi finally took the hand that was being held out to him, and grasped it tightly The Rebbe spoke for 15 minutes. This was very different from all other Yechidus’n. A few days later, after Yud Shevat, my zaide realized that this was the Rebbe’s final good-bye to him.

Reb Chaim Zvi believed strongly in purifying the air with words of Torah. So he was especially happy, in the early 1950s, to be invited to speak on the radio at the invitation of Rabbi Herschel Fogelman, zohl gezunt zein, shliach in Worcester, Massachusets. My zaide believed that the words of Torah would purify the air wherever the radio was being played. Rabbi Fogelman still recalls the way he held the microphone, with reverence. He would speak with great feeling, and sometimes he would close his eyes and sing niggunim, on the radio.

”When I was a bochur, I went to his shiur in Tanya, in Williamsburg,“ said Rabbi Herschel Fogelman. ”It was vahrem and good; he was fire!“

One of Reb Chaim Zvi’s innovations to further Yiddishkeit in the United States was to prepare and distribute Torah records commercially. Until then, only cantorial, Yiddish comedy, and folk songs were available! Reb Chaim Zvi made three records (one on Shmiras Shabbos and two on Emunoh). Later, Reb Chaim Zvi made reel-to-reel recordings of shiurim (interspersed with niggunim) which were originally called Kol Torah (see label below.)

From their places in Gan Eden, Reb Chaim Zvi and Rebbetzin Bryna Konikov are surely having the nachas they so richly deserve. Many of their children and grand-children live in distant places all over the world, valiantly serving the Rebbe as his shluchim in Englewood, New Jersey; Satellite Beach, Florida; Orlando, Florida; South Orlando, Florida; Daytona Beach, Florida; Ft. Lee, New Jersey; Roslyn, Long Island; Southampton, Long Island; Melbourne, Australia; Malvern, Australia; East Bentleigh, Australia; Glen Eira, Australia; East S. Kilda, Australia; Bondi, New South Wales; Johannesburg, South Africa; London, England; and Sussex, England.

On the 24th of Tammuz, we commemorated the 56th Yahrzeit of the passing of the ”Rov veRoeh B’Yisroel,” as the Frierdiker Rebbe called him… the Chossid whom I am blessed to call my zaide.

Esther Caplan would like to express her gratitude to the following people for assisting her in the research for this article: her uncle, Rabbi Velvel Konikov; her brother, Rabbi Chaim Zvi Konikov; her aunt, Rebbetzin Devorah Groner; and her childhood teacher, Rabbi Yisroel Gordon.

Yossel

The Konikovs are an AMAZING family. I was privileged to grow up around the corner from Reb Velvel, his wonderful wife Barbie a”h and their great kids in Worcester. Their generosity and hospitality was second to none. They helped me in my journey toward Yiddishkeit and Lubavitch and I will always remember the wonderful Shabbosos and Yomim Tovim I spent in their warm loving Chassidishe home on Richmond Avenue.

Pinchos Woolstone

let the neshomos of such heilige yiddin protect us and our kinder un einiklech biz moshiach vert kummen

May Rebbetzin Groner continue to shep nachas from her kinder kintskinder un kints kintskinder.

May the memory of her illustrious husband strengthen us all, in these last moments of the Golus.

May HaShem have rachmonus on his Am Yisroel un shik unz der Rebbe gleich jetzt now