Still Fighting Anti-Semitism, 93-year Old Holocaust Survivor Cherishes His Bar Mitzvah

by Rochel Schwartz – chabad.org

Faced with rising anti-Semitism, Jewish people everywhere have been searching for ways to make a difference and to combat such sentiments wherever they are found. For one elderly man, the choice was clear. During a beautiful Shabbat ceremony at the Chabad Jewish Center of Ridgefield, Conn., Henry Eisen, a 93-year-old Holocaust survivor, chose to celebrate his bar mitzvah some 80 years after he was deprived of one in war-torn Poland.

Henry, lovingly called “Hesh” by his family and close friends, lives in Queens, N.Y. But when he spends Shabbat with his children in neighboring Connecticut, he attends services at Chabad of Ridgefield, a community that he says reminds him of his childhood in Rymanow (known in Yiddish as Rimanov), a storied Jewish town in Galicia.

Henry is one of three children born to Joseph and Cylia Eisen. His father was a cattle trader in Rymanow before September 1939, when Nazi Germany invaded Poland, and his family’s world turned upside down. He fondly remembers the bar mitzvah of his older brother, Nathan, and recalls thinking that soon he’d have one as well. That dream was short-lived when it became apparent that the German army was advancing; the Nazis entered Rymanow on Sept., 8th 1939.

The Nazis had sent “lookouts” to the village to ensure there would be no resistance on the part of the Jews who lived there. Henry’s mother had a restaurant that one of the German soldiers would frequent, he recalled. Risking his life, the soldier urged his mother to flee with her family and even arranged for a truck to pick them up from Rymanow and take them 17 miles east to Sanok, a small town on the banks of the river San, at the time the border demarcating Nazi-occupied Poland from Soviet-occupied Poland. From Sanok, the family crossed the river to the nearby town of Lesko, then under Soviet control. A family that owned a bar gave Henry’s family a place to stay.

Hoping to travel back to Rymanow to retrieve some of the family’s belongings, Henry’s father began seeking a route home. After finding out that the only accessible route back to Rymanow was a bridge that remained open, Henry’s father packed some bags and traveled across the river. Having not heard from his father in a while, Henry’s brother Nathan decided to travel across the river to seek him out.

The Russians, who had signed a nonaggression pact with the Nazis, arrested Nathan before he was able to reach his father and he was sent to the Gulags, the Soviet network of labor camps. Meanwhile, Joseph was caught in Nazi territory. In 1942, the Nazis began deporting the Jews of Rymanow, some to the Plaszow death camp, and the rest to Belzec, where Joseph was sent and eventually perished.

Back in Lesko in 1939, Henry and his family had no clues to the fate of their father or brother.

A Deceitful Soviet Ultimatum

The Russians then gave the people living in Lesko an ultimatum: Either they could stay in Lesko, or they could move to German-occupied Poland. This was a ploy to ascertain where the allegiance of the people lay. In the hope of reuniting with their father, Henry’s mother decided that it would be best for her and her two young children to move back to the German side. Because they registered to move to the German side, the family was arrested and sent to Siberia by the Russians, where they found themselves in a labor camp cutting lumber. They were given a daily allotment of bread and able to obtain extra food from nearby Russian farmers. Soon, rumors began to spread about what was happening in German-occupied territory.

When the war ended, Henry’s brother Nathan was released from the Soviet labor camp. After inquiring about his family from others, he found out their location and traveled by train to the nearest station. He then walked the 10 miles home.

There, in their home in Siberia, the family found out the devastating news that their father had been murdered in Belzec. Eventually, the Russians informed the family that they were free to leave and they set out for Soviet Uzbekistan. In Bukhara, Henry Eisen, now 17, began selling shoes and making cigarettes to raise money to support his family.

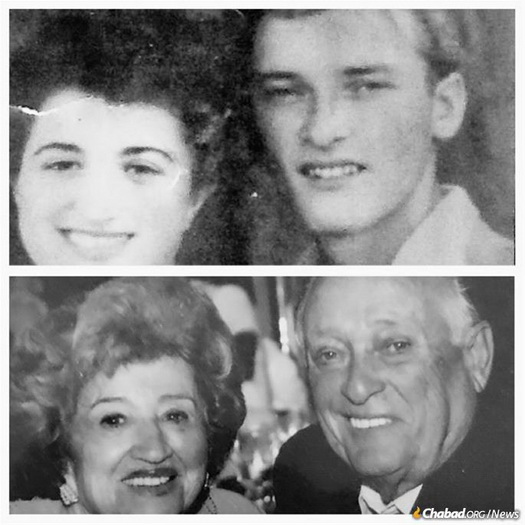

The Eisens then moved to Frunze (today Bishkek), Kyrgyzstan. There they heard that many Jews were safely making their way back to Poland, so they slowly made their way by train to Krakow, near their hometown of Rymanow. But Krakow was also unsafe. The family left and wound up in a Displaced Persons’ Camp in Germany. There, Henry met his wife, Fanny Gitelman, and they were moved to a DP camp in Foehrenwald, Germany, where Henry’s oldest son, Mel, was born.

A New Life in America

With their new baby in tow, they left for a new life in the United States. Henry settled in New York and got a job painting houses, later working as a food merchant. Henry’s daughter Sharon was born in New York. They were eventually joined by more of their extended family members.

The idea of Henry having a bar mitzvah originated from Rabbi Sholom Deitsch, co-director with his wife, Chanah, of Chabad of Ridgefield.

“My father was hesitant at first,” says Mel Eisen. “The painful experiences of the Holocaust were likely to be triggered by celebrating a bar mitzvah, considering the grounds on which he had been deprived of one. But my father really fell in love with Rabbi Deitsch and with the community. The genuine warmth and respect that Rabbi Deitsch showed my father coupled with the friendly and welcoming atmosphere of the Jewish community in Ridgefield, both of which remind him of his childhood before the war, were the final push for my father’s decision to celebrate this special event.

“Our community in Ridgefield is very close-knit,” he continues. “It’s heimish [homey], everyone knows everyone. Everyone knew about my father’s bar mitzvah when it was still in its planning stages, and the members of the community were excited for the event because they knew it was bound to be a unique and special experience.”

And so, last month, after 80 years, Henry was called to the Torah and celebrated his bar mitzvah with loved ones and friends in an emotional scene.

“It was an unbelievable experience,” says Mel. “Everyone cried; the rabbi, the community members. It was very touching.”

Mel explains that after the bar mitzvah he asked his father how it had felt. The answer shocked him.

“He told me: ‘It was the greatest moment of my life,’” says Mel. “I asked my father if it was indeed more special than when he got married or had his first child or came to America, and he answered ‘Yes.’ This was a special moment that was taken away from him, and now he finally experienced it.”

“We will never forget what happened,” Mel ends off. “Especially in today’s world with all of the recent anti-Semitic-attacks, we need to tell stories like these to ensure that something like this will never happen again. I have tremendous admiration for Chabad.org for telling these stories. We will never be destroyed, ever.”