Story: A Tanya Printing in War-Torn Lebanon

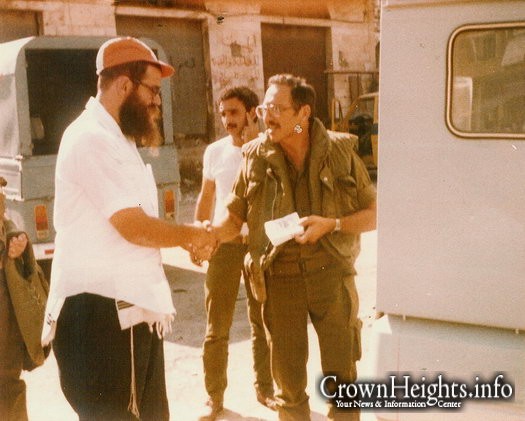

Rabbi Aharon Eliezer Ceitlin, OBM, who passed away yesterday at the age of 62, related the following story that he experienced while on Shlichus in Erezt Yisroel during the Lebanon war in 1982. The story was transcribed by Rabbi Shmuel Lesches, Maggid Shiur in Yeshiva Gedolah of Melbourne, who heard it from Rabbi Ceitlin at a Farbrengen, and later shared the transcription with him to review for accuracy.

Relates Rabbi Ceitlin:

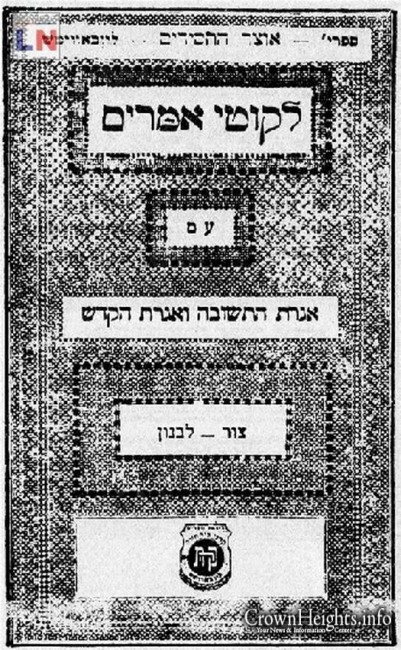

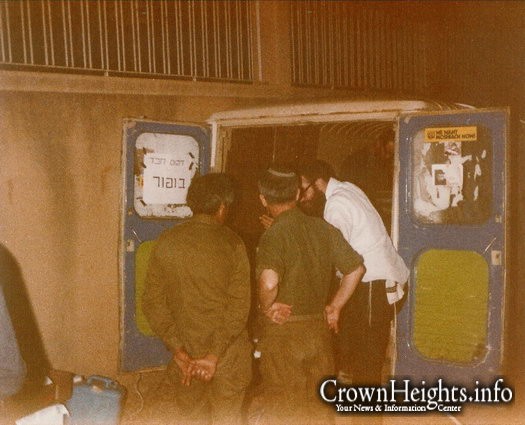

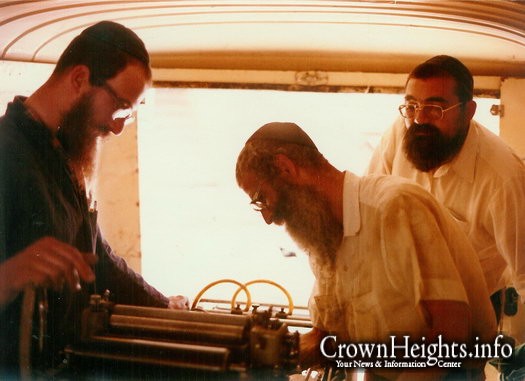

In 1978, the Rebbe initiated a campaign to print an edition of Tanya in every country in the world. This directive was based on a teaching of the Baal Shem Tov, that Moshiach will come when the wellsprings of Chassidic teachings spread worldwide. Printing the Tanya in every location would transform that place into a source and bastion of Chassidic teachings. Furthermore, when a Jew realizes that an edition of Tanya was printed in his city, he will be more enthusiastic about studying it.

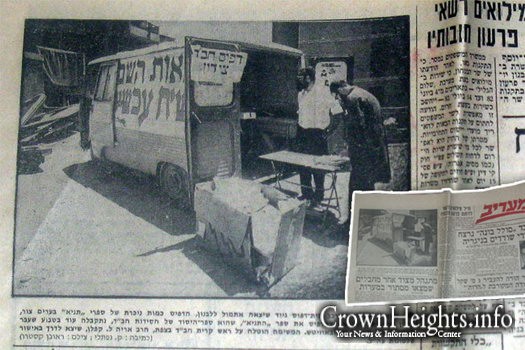

When the Lebanon War broke out in the summer of 1982, the Rebbe directed Rabbi Leibel Kaplan ע”ה, the head Shliach (emissary) of Tzfat (Safed) – and an alumnus of the Rabbinical College – to print the Tanya in Lebanon. The Rebbe’s instructions were quite specific, that the Tanya should be printed in as least three Lebanese cities that once had thriving Jewish populations, and which were currently occupied by the IDF. The directive was to print the Tanya in all of these places, regardless of how many copies were printed.

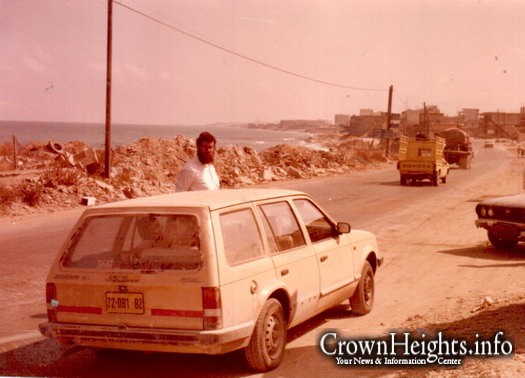

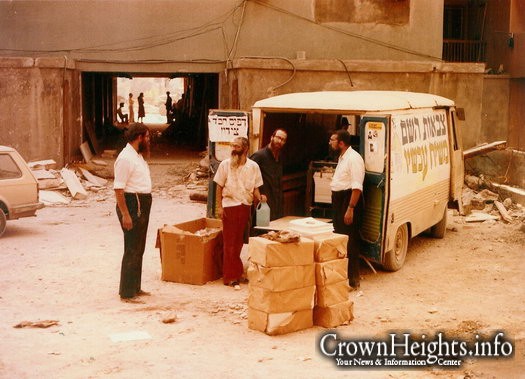

Immediately upon receiving these instructions, Rabbi Kaplan formed a committee to begin putting the plan into action. It was relatively easy for us to procure the equipment, which included a van, an electrical generator, a printing press, and the printing plates of Tanya. However, it was much harder to obtain a permit from the IDF allowing us to enter the war zone in southern Lebanon. Rabbi Kaplan asked various influential Chabad figures to use their connections to obtain the necessary permit. They received a number of assurances, but the permit did not eventuate.

Meanwhile, we began receiving nightly calls from Mazkirus (the Rebbe’s secretariat), requesting an update. This extraordinary sign of the Rebbe’s interest in the matter obviously encouraged us to work even harder. At the same time, we became more and more dejected as we realized that we were not any closer to fulfilling the Rebbe’s wish.

It came to a point where we really did not know what to do. We had received numerous assurances that we would get a permit, but the fact remained that we didn’t. We couldn’t help feeling that we were being given the run-around. In desperation, Rabbi Kaplan suggested that we just drive to the border without a permit, and try to get into Lebanon.

We set out on a Thursday afternoon, and we arrived at the border after an hour of driving. We got out of our vehicle, and immediately began doing what Chabad does best. We said L’Chaim with the soldiers at the border, and sang and danced with them. The soldiers enthusiastically participated in our activities. But, when we tried to continue travelling north, their demeanour changed. They made it very clear that there was no way for us to proceed without a permit.

Having no choice, we remained at the border. Each of us started focusing on a different mission; one of us put Tefillin on the soldiers going in and out of Lebanon, and another began signing up each soldier for their own letter in a Sefer Torah. I was given the task of trying to resolve the impasse. I immediately began making a series of free-of-charge calls from a row of telephones that the army had set up for the convenience of its soldiers going in and out of the war zone. There were times when I thought that I was making progress. However, after six hours, we still did not have the necessary permit. We left the border at 10:00pm, and returned to Tzfat completely demoralized.

We reconvened as soon as we arrived back in Tzfat, and we resolved to immediately set out to the headquarters of the IDF Northern Command, situated in an army base at the outskirts of Tzfat. We arrived before midnight, and waited as the sentry sought authorization from his superiors to admit us. After a couple of minutes, we were allowed into the base, and we presented our case before one of the officers. He was very cordial, and told us that he knew all about the Rebbe. He advised us to return the following day, for the Chief Military Rabbi of the IDF would be visiting the base. Perhaps he could help us.

We returned to Tzfat, yet again without the necessary permit. We disbanded, and naturally headed for bed. However, I was unable to fall asleep. It bothered me terribly that we had spent many days trying to fulfil the Rebbe’s directive, and we had still not succeeded. The Rebbe’s secretaries were calling every night, and we still did not have the good news that the Rebbe awaited. What was I doing in bed?

I immediately jumped out of bed, and quickly got dressed. I rushed over to the house of one of my colleagues, and pounded on his door. He eventually opened it, and I said, “Hurry, get dressed, we are returning to the headquarters of the Northern Command to meet the commanding general and demand a permit!” He responded, “Aharon Leizer, relax, it is past midnight. Go get some sleep.” I could tell from the tone of his voice that he thought I had become unhinged due to the stress of recent days.

I responded, “I am going to the army base whether you join me or not. If you wish to have a share in our success, then come with me. If not, I will go myself, and the merit of successfully fulfilling the mission will be mine alone.” He responded, “Nu, so go.”

I got into my car and drove towards the army base. I was not even sure how I would get into the base. What would I tell the sentry? That I needed to get into the base to speak to the general at 1:30 in the morning, in wartime, so that I could print some books?

I zoomed towards the army base at high speed, and screeched to an abrupt stop. I jumped out of the car and yelled at the sentry, “Where is the general? Quick, tell me where is the general? I need to speak to him!” The sentry must have thought this was a real emergency, and he immediately opened the gate for me and pointed out the general’s quarters. I still can’t believe that this happened; it was nothing short of miraculous. I have visited the army on hundreds of occasions, and never was I admitted without the sentry first obtaining approval from his superiors.

Once inside the army base, I immediately headed to the general’s building, even though I wasn’t sure whether he was physically present at the base. The general’s living quarters were upstairs, and his suite of offices was downstairs. I entered and told the secretary that I needed to speak to the general immediately. She burst out laughing and responded, “Impossible. It is wartime, and the general is extremely busy”.

I pleaded with her, “Please, I am not asking you to decide whether the general can meet me. Let the general decide that. Please inform him that someone from Chabad is here to see him urgently on an extremely important matter.” However, my words fell on deaf ears; the secretary did not budge.

Out of sheer desperation, I told the secretary, “Just remember that I came to tell the general something extremely important and urgent – something relevant to the whole outcome of the war. And, just remember that it was you who did not allow me entry.” When the secretary heard these words, she became slightly anxious. She agreed to relay my message to the general, but not before assuring me that there was no chance that he would agree to see me.

When she returned, she told me to wait; the general would see me shortly. I pinched myself to make sure that I wasn’t dreaming. I waited until the general sent for me. I climbed the stairs, with the secretary following closely behind. When I came face to face with the general, I could see that he was exhausted and tense. He was not exactly in the type of mood I had hoped to find him.

For lack of a better way to start the conversation, I remarked that it looked like the general had not slept that night. The general snapped back, “Not just one night – I haven’t slept for several nights!”

At that point, the secretary asked whether she could remain at the meeting. She wanted to hear my message to the general, and what was so urgent about it. I jokingly replied that my message was classified as a military secret, and only the general could hear it. When the general heard this, he burst into an uncontrollable fit of laughter. He laughed and laughed, and it took him a moment or two to compose himself. When he did, he seemed a lot calmer and friendlier. Of course, the secretary was allowed to stay as well.

I turned to the general and said, “Listen, I would like to present a matter which I feel affects the whole outcome of the war. I hope the general will view it as such. The Lubavitcher Rebbe, the leader of the generation, has requested that the Tanya be printed in Lebanon. Why? Don’t ask me; I am not the Rebbe. However, I can say that Tanya is the seminal work of Chabad, and that the Rebbe has arranged for it to be printed all over the world. If he wants it done in Lebanon, it is obviously of upmost importance.” I went on to tell the general about several incidents where the Rebbe had issued a directive whose purpose was not understood at the time, but which became clear in hindsight. For example, I told the general how the Rebbe had directed his followers in Israel to organize mass prayer rallies of children in September 1973. No one understood why, until the Yom Kippur war broke out shortly after. I also showed the general several Tanyas that had been printed in cities around the globe.

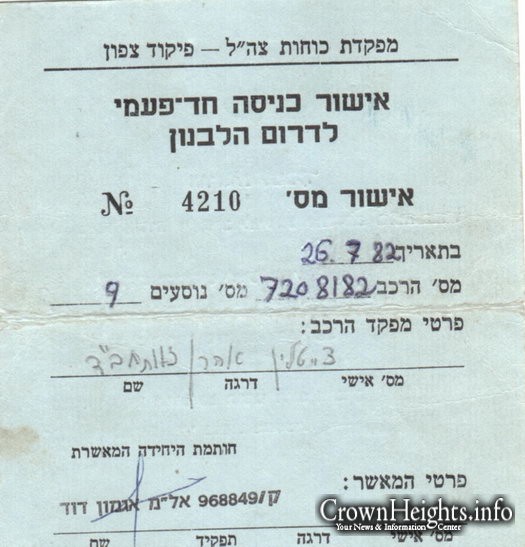

When I finished my fifteen minute speech, the general asked, “Nu, so what do you want from me”. I explained that we needed a permit to get into Lebanon. He said, “No problem, you have my permission to enter Lebanon”. I immediately responded that I needed the permit in writing. The general said, “No problem.” He picked up the phone and instructed the officer at the other end to write out a permit for us to enter Lebanon. Over the phone, I could hear the officer respond, “To where in Lebanon?” I thought, “Oh no, I forgot to tell the general that the first printing will occur in the city of Tzor (Tyre)”. Based on the Rebbe’s directives, we had decided to print in the cities of Tzor, Tzidon (Sidon) and Beirut, and we had chosen Tzor to be first. To my great relief and amazement, the general responded, “You know what? Allow them to travel until Tzor.”

The meeting was now almost over; successful beyond my wildest imagination. I thanked the general profusely, and I asked for his and his mother’s names, so that I could forward it to the Rebbe for his blessing. He responded that I should just tell the Rebbe that the IDF Commander of the North had provided the permit.

I headed to a nearby building to obtain the permit. A young officer opened the door, and immediately asked whether I was a Chabadnik. I replied in the affirmative. He got all excited and immediately started exclaiming “En Kemo Chabad” (“there is none like Chabad”). Sitting around the room were several soldiers unwinding from their long day. The officer hustled them to their feet and led them in a dance around me to the tune of Uforatzto. Then, the officer excitedly began recounting how Chabad had helped him on a recent trip to Paris, tending to both his physical and spiritual needs. I listened to him for a couple of minutes, but then I steered the discussion to the matter of the permit. Of course, it was helpful that my “business partner” was such an avid fan of Chabad.

The officer asked, “When do you want to go to Lebanon?” I replied, “Right now”. The officer responded, “Impossible”. I was quite familiar with IDF bureaucracy, and I immediately started to panic, thinking that the officer was trying to withhold the permit unnecessarily. However, I needn’t have worried. The officer explained that we could not enter Lebanon in the middle of the night, but that we could enter after 4:00am. This suited me quite well; it left me with just enough time to get back to Tzfat and round up my colleagues for the hour-long drive to the border.

The officer then asked if we had weapons. Of course, we Chabadniks were without weapons. I started to panic again, worrying that the officer would refuse the permit if we were defenseless. I hastily tried to introduce to him the concept of “Shluchei Mitzvah Einon Nizokim”; no harm befalls agents performing a Mitzvah. The officer grinned broadly when he heard my explanation, and he told me that it was not good enough. My panic went into overdrive. However, the officer reassured me, “Not to worry. At 4:00 in the morning, be at the border, and I will have an army escort prepared for you; four soldiers on an armored jeep.”

With that, he reached over to a pile of cards which had been pre-signed by one of the Deputy-Generals of the Northern Command. The officer filled in all the details, and he added just above the signature, “Please help these men of Chabad as much as possible”. He handed the permit to me. For the second time that evening, I pinched myself to make sure that I wasn’t dreaming.

I was delirious with joy. I immediately drove back to Tzfat in order to round up all the members of our group. When I woke them with the news that I had obtained the permit, they thought I was out of my mind. But there was no denying that I had the permit in my hand, and we quickly set out to the border.

Rabbi Ceitlin relates the rest of the story in this Living Torah video, produced by JEM:

f.s.

Listening to Rabbi Ceitlin obm gives us strength and hope that we can overcome challenges and succeed. What a story and what an exceptionally devoted chossid! Redoubling our efforts to carry out the Rebbe’s shlichus and our unity will certainly protect us and bring the ge’ula – may it be now.