A Teacher in Paris: Rabbi Shmuel Azimov

Emissary of the Rebbe to Paris since 1968, Rabbi Shmuel Azimov is credited by many of France’s Jews for the sweeping changes that have turned Paris and its surrounding areas—once a Jewish wasteland—into a vibrant hub of Jewish life. Over the years, they have flocked to him, seeking his mentorship, guidance, and friendship.

With his deep-rooted Chabad Chasidic world-view and a profoundly compassionate concern for others, “Moule” (short for Shmuel), a household name in France’s Jewish circles, has negotiated every aspect of Jewish communal life, working cooperatively and effectively with all of the city’s Jewish organizations and municipal authorities. Together with his wife, the late Bassie Azimov, he opened Paris’s first Chabad House in 1972. Under his leadership, Chabad centers have since opened in every district of Paris and its suburbs, most recently in the Champs Élysées.

Anti-semitism is on the rise in France. Recent attacks in Toulouse in which four Jews were murdered, and the violent attack in June on yeshiva students in Lyon are deeply worrisome. France’s Jews are calling on the government to take more aggressive measures to put an end to the violence against Jews. Rabbi Azimov is hopeful, he says, that authorities will work swiftly and effectively so that its Jewish citizens do not need to live in fear.

France is home to one of the largest Jewish populations in the Diaspora, and Jewish life in Paris, where some 375,000 Jews reside, is thriving. With forty Chabad centers and some 170 Shluchim in Paris, a day school bursting at the seams with 2,000 students, and an annual budget of roughly $25 million, Rabbi Azimov has built and continues to grow a remarkably successful Jewish infrastructure.

We chose to interview Rabbi Azimov for this issue of Lubavitch International, and gain some insight into this man who thousands call their teacher.

Paris 2012

Rabbi Shmuel Azimov shuffles slowly into the dining room of his Paris apartment where I wait to meet him. The sixty-six year old rabbi suffered a stroke thirteen years ago, leaving his speech and movement impaired, but he has graciously agreed to talk with me.

A warm, lively vibe fills the high-ceilinged ample rooms that are cheerfully cluttered with family photos. The apartment appears well-lived-in. Children and grandchildren come and go. During our meeting, Rabbi Azimov’s son and several of his granddaughters poke their heads in to ask him a question. A young man comes in asking for help. Rabbi Azimov is non-discriminating in his affable attentiveness and concern.

We talk for several hours, the conversation punctuated by his gentle humor and soft laughter. I remind myself that this is a man still in mourning. His wife and partner in life, Bassie Azimov, passed away quite suddenly six months ago. The two had been married for forty-five years; together, they raised a family and a phenomenon.

Today, the Azimovs are credited by many of France’s Jews for the radical transformation that has made the city of lights a lively Jewish metropolis. I’ve come prepared to hear Rabbi Azimov discuss his early struggles, the great aspirations, the vision and the strategy that he and his wife nursed as they set out on their lifelong mission as Chabad Shluchim to Paris.

But the dyed-in-the-wool Lubavitcher Chasid is altogether understated about his prodigious success. I press on. Surely he and his wife devised a plan, nurtured a dream, conceived a schema that would help explain his considerable following and the dramatic success of his shlichut.

Not really. He and his wife, he tells me plainly, were just teachers.

They taught one child, one teenager, one adult at a time. They taught groups, they taught college students, they started a school. Between the two, hundreds, and eventually thousands of Jews would study Torah. The Azimovs filled their days and their evenings teaching. “Moule” made his rounds at all major and local universities in Paris, seeking out Jewish students who welcomed the chance to join a Torah study class. His wife reached out to local families, teaching the women, their daughters, and college girls, so they would want to marry Jewish, and live as Jews. Nothing more elaborate, nothing more grandiose or glamorous than finding Jewish people who would accept the invitation to study Torah.

Slowly but surely their students took an interest not only in studying, but in living Jewishly. And then they became Chabad Shluchim. In the 1960s, with the influx of Jews from Algiers, Tunis and Morocco, France’s Jewish population grew rapidly. Jewish communities blossomed. Success begat success. Today, Beit Chaya Mouchka, the Chabad Jewish school in Paris founded by Mrs. Azimov and her husband—a $22 million complex when it was built 20 years ago—counts two thousand students from preschool through high school.

Chasidic Upbringing

Shmuel Azimov was born in Russia, in 1945. He was three years old when his family arrived in Paris after fleeing communism. For most Chabad Jews escaping communism, France was a point in transit—either to the Holy Land or North America. The Azimovs were among the few Chabad families who remained. There were not many Jews in Paris; most were disaffected Holocaust survivors, and the city was largely devoid of any real Jewish activity.

Rabbi Azimov got his early grooming as a teacher from his father who went door to door searching for students. Chaim Hillel Azimov founded 20 Talmud Torahs in Paris and its surrounding areas.

When he was old enough, he went to the Chabad boys yeshiva founded in Brunoy in 1947, by Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe. In 1963, then a teenager, Rabbi Azimov made his first transatlantic trip to see the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe, traveling by charter flight from London.

“I was one of three Chabad boys from Paris who lived in the yeshiva dormitory. After returning from my first visit to the Rebbe, the three of us were instructed to start our activities as shluchim in Paris while continuing our studies in the yeshiva in Brunoy. So every Shabbos, we would return to the city. There were many children of Holocaust survivors who assimilated. But we reached some, we began to learn with them, to teach them, and eventually, they joined us in the yeshiva in Brunoy.”

The boys kept up a regular correspondence with the Rebbe, informing him of their activities. The Rebbe wrote back with instructions. (The letters were evenly divided among the three of them; Rabbi Azimov retained seven letters.) At some point, his two friends continued their rabbinical studies in New York. So when he came next to see the Rebbe in 1965, he asked the Rebbe if he too, should remain in New York.

“My meeting with the Rebbe (yechidus) was at 6 a.m. The Rebbe told me to return to Paris, and he blessed me with “great success.” He then said to me, “Do you know what ‘great success’ is?”

“It is success beyond your expectations,” he told Azimov.

There are many ways to measure success, but by all accounts—by the numbers of Jews who have been reached, and by the opportunities for Jewish engagement that the city’s Jewish population enjoys today—it is indeed “success beyond expectations.”

The Organic Teacher

More interesting yet, is the organic nature of Rabbi Azimov’s success. Almost all of the 170 shluchim serving in Chabad centers in Paris were his and his wife’s students. It is a story that reflects a highly functional family, or the dynamic of an exemplary teacher/students relationship.

As per the guidance he received from the Rebbe, Rabbi Azimov makes a point of knowing the character of the individual in his employ. “It helps to know what each one wants to achieve from his shlichut. It helps to know what responsibilities are suitable for each one.” And when something doesn’t work out, the teacher in him gently steers his students into another position that they are better suited for. “There’s enough work here for everybody, so that if someone isn’t doing well in one area, they adjust to something else.”

Azimov is ever cognizant of the Rebbe’s foresight. When once asked by the Rebbe whether he plans to expand his activities, he said, “If the Rebbe will send Shluchim, we will expand.” But the Rebbe had something else in mind. “I will not send Shluchim,” The Rebbi said. Instead, he told Azimov, there are young people in France who have become involved in Judaism. “Teach them and they will become Shluchim.”

After his marriage to Bassie Shemtov in New York, the couple returned to Paris. Arriving on the eve of the May 1968 student protests, the Azimovs inspired a grassroots transformation of their own. They continued to receive the Rebbe’s guidance: Rabbi Azimov and his wife should teach as much as possible. The Rebbe specifically instructed Azimov to dedicate half of his time to teaching in a formal school.

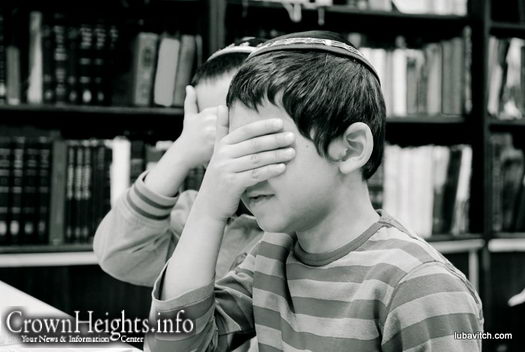

“I became a teacher in the Lubavitch school for boys, and eventually at the one for girls as well.” At a time when no one saw a yarmulke in a French university, Rabbi Azimov, in full Chasidic regalia, fearlessly toured the campuses. “I began to give Torah study classes at all the different universities in Paris—not as part of any formal university curriculum, but for Jewish students who were interested.” His wife also taught classes to women and girls.”

What did he teach, I ask him?

“I taught Torah. I taught the value of the mitzvahs. I taught about the importance of traveling to see the Rebbe. What is good for me, I must share with others. If I am a Chasid, I must offer my student the same opportunity, the same experience of yiddishkeit that I want for myself.”

Rabbi Azimov traveled regularly to the Rebbe who took particular interest in seeing and guiding the growth of Jewish life in Paris, where he and his wife lived for a period of seven years, beginning in 1935. “We’ve sown the seeds,” the Rebbe’s wife once told Rabbi Azimov, reflecting on that period of her life in Paris.

“Your work is to reap the harvest . . . .”

At a Chasidic farbrengen on Simchat Torah in 1973, the Rebbe, called for “a revolution in France against the evil inclination.” At that memorable event, the Rebbe suddenly surprised the audience as he led in the singing of Le Marseillaise to the words of ha-aderet v’ha-emunah, from the Siddur. It was thus that the French national anthem, popular today among Chabad Chasidim, was appropriated, as it were, by the Rebbe as a Chabad niggun.

I ask Rabbi Azimov what he did to make the “revolution” that the Rebbe mentioned. “We simply continued to teach Torah. Granted, not everyone is a scholar. But everyone was receptive on some level.” Soon the Azimovs’ classes began to draw large crowds.

If good teaching is a factor in shaping the life choices of students, the Azimovs were remarkable teachers. And if teaching by example is ideal, the Azimovs were consummate teachers. When a certain standard of kosher dairy that Rabbi and Mrs. Azimov used and which they taught their students was necessary in the observance of kosher—even for babies—was not available to Jewish families in remote areas of Paris, Rabbi Azimov traveled by train carrying the dairy products, which he personally delivered to these families. Eventually, kosher food became available.

Reaping the Harvest

Chabad centers opened in every one of Paris’s 20 districts, and in Montparnasse, in Orteaux, in Place des Fetes, in Flandre, and in numerous suburbs of Paris, making it easier for young Jewish couples choosing to adopt an observant lifestyle. Kosher consumption grew, and kosher restaurants opened—today there are some 130 kosher eateries in Paris.

I try to reconcile the thriving Jewish life I see in Paris with media reports of growing anti-Semitism. It is a problem, says Rabbi Azimov, as it is a problem in many other places. But he trusts that the authorities will do what they must to ensure a change in the climate. Here and there Jews are making their homes elsewhere, but they are not leaving in droves by any means. In fact, with one of largest Jewish populations in the world (approximately 500,000), there is enormous opportunity for Jewish life in France.

Martine Uzan is principal of the 500-strong Beit Chaya Mouchka preschool. The product of Parisian public schools, Martine met the Azimovs as a young woman. Her husband was a university student at the time. Slowly but surely, their lives began to shift. The Azimovs’ integrated sense of purpose and identity made the Uzans want to learn from them, she explains. “The relationship they had with people was genuine. They were very focused, and every conversation with them resulted in some practical decision” towards a deeper commitment and identity.

It is clear that what Martine and the others found in both the rabbi and his wife was not charisma, but a quality of candid honesty. “Their clarity about what was right, what their purpose was, and the courage they had to do what they felt needed to be done,” explained Uzan, was rare, and made others want to rise to the opportunity to live more nobly.

Perhaps it is the result of a Chasidic sensibility cultivated over generations that results in a profound self-knowledge. Both Rabbi and Mrs. Azimov trace their Chabad lineage several generations back. Daughter of the legendary Rabbi Bentzion and Esther Golda Shemtov who met and married in Siberia where they survived four years of punishing exile for their dedication to Jewish education, Bassie was raised in a deeply entrenched Chasidic home. Her parents were representatives of the sixth Rebbe to London, where she grew up.

As is true of most Chabad centers around the world, Azimov guides Shluchim in Paris to achieve financial independence. But the paternal sentiments in him cushion the process, making it easier for them to find their footing. “I don’t think it is right to put a young emissary to work in difficult circumstances. I don’t want the Shluchim to feel that they are lacking.”

Today, Rabbi Azimov’s budget has grown to about $2 million a month. How does he sustain this consistently, especially in this economy, I ask?

“We are fortunate that we have many supporters.” Jews all over France, even those who are not formally affiliated, had their entry to Judaism through Chabad, and they continue to be grateful, especially for the impact that the Azimovs have had on the Jewish experience in France. Many choose to support his activities, and Rabbi Azimov appreciates the broad base of small donors. “It is better to have many people who want to participate in Jewish life, rather than a few major players,” he says.

Reflections

After suffering a stroke in 1998, he was forced to take a slower pace, at least physically. Yet he continues to maintain responsibility for his budget, and he continues to teach in school as the Rebbe instructed him to do half a century ago. No longer able to lead a class as he once did, he now works with students individually. I ask why he continues given the difficulties.

“I once asked the Rebbe if I may dedicate full time to my administrative activities, but he insisted that I continue to teach half a day in school. He said ‘there are reasons’ that I should be teaching every day. I don’t know what they are, I never asked.”

What, I want to know, is most important to Rabbi Azimov in his role as a teacher? “To understand where the individual comes from, what their personal, emotional and intellectual inclinations and abilities are, and how to teach them in a way that empowers them to then teach themselves.”

Today, Rabbi Azimov has the benefit of perspective, of hindsight. He has seen the dots connect, the blessings fulfilled, the privilege of guidance that proved foresight and vision.

“When we sent the Rebbe plans of the school building, he asked: ‘Does this plan include everything?’”

Azimov understood that to mean that enormous as the complex was, it was still not big enough. “So we revised the plans, and miraculously managed to get approval to add another story to the building.” The Rebbe’s remark made it possible for them to squeeze as much usage and capacity out of the building for years, before outgrowing it. Today, the school is looking for additional space for the September school year.

As I get ready to leave, Rabbi Azimov says, almost to himself, “Some people believe that the Rebbe’s blessings are a spiritual matter. I have seen rather that their fulfillment is revealed, physically, materially.”

He recalls the time he sent the key to the first Chabad House which he opened in Paris, in 1972, to the Rebbe’s secretariat. When he next saw the Rebbe in a private audience, the Rebbe thanked him. And then, Azimov recalls, “the Rebbe blessed me. He said to me ‘G-d should help that you can say that this space is too small for us.’

Photos by Israel Bardugo, Mendy Hechtman, Levik T., Mendel Benhamou and Meir Dahan

Inspiring

A beautiful article with stunning pictures. Yasher Koach!

Admirers of R- Azimov

A true chossid, if ever there was one; Has accomplished the most amazing things together with his late wife: May he have long gezunter yohren iy”h.

a great man

What one man can accomplish is unbelivable. may hashem strenghthen him.

French Revolution

A true shaliach of the Rebbe. Unlike so many, he builds buildings that Yidden really use, and unlike today’s crop of wannabes he isn’t in shlichus as a business.

If there were more shluchim and heads of moisdos like Reb Moule, there would be fewer problems in Chabad today.

Milhouse

Actually the Lubavitch cheder in Paris was founded by Reb Zalman Serebryanski. When he left for Australia in 1949, Reb Hillel Azimov took it over.