Antagonizing Our Evil Inclination, The “Misoninim” Syndrome

Amongst the varied items for which we seek forgiveness in the confession prayer recited on the holy Yom Kippur, is a somewhat odd class of transgression: “The sins which we have committed before You with the ‘Yetzer hara,’ (evil inclination).”

“But,” as my early days spiritual mentor would rhetorically muse, “Aren’t all sins preformed with the evil inclination? Surely there are no sins committed with the ‘Good inclination?’”

“The sins which we have committed with the evil inclination,” he would offer as a rejoinder, “Refers not to sins which the evil inclination had managed to drag us into, but rather to sins into which we had managed to drag our evil inclination.”

Sometimes the Yetzer Hara lies dormant; not interested in us, yet we go ahead and agitate it: “Nu, what’s the matter with you? Wouldn’t this or that indulgence be pleasurable? Come on get to work!”

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

If someone were to tell you that tens of thousands of grown adults had taken to the streets, weeping bitterly over their sad state of “Beef deprivation,” you would likely treat it like a joke. You might check your (spiffy electronic) calendar to make sure it’s not April 1st.

Yet this strange scenario is not in the least a hypothetical construct or in any way flippant. The Amalgamated Meat-Deprived Victims was a real phenomenon. The subjects of this bizarre and unruly occurrence were our very own ancestors.

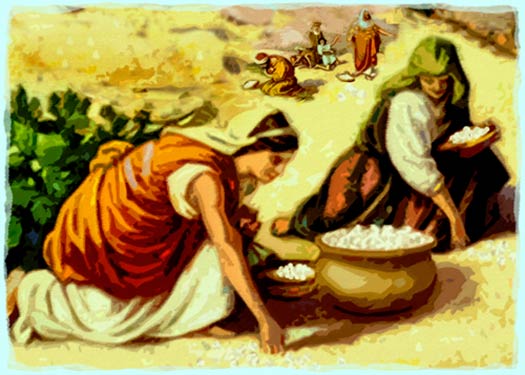

It happened soon after their liberation from Egyptian bondage, at the very outset of their journey through the desert towards the Promised Land when things went bad: “The rabble that was among them cultivated a craving,” states this week’s Parsha, Beha’aloscha, “And the Children of Israel also wept and said, ‘Who will feed us meat?’”(Numbers 11:4).

The self pity of the beef deprived victims is as baffling as it is amusing, for after all, since when do adults weep over missed beef, even if they haven’t had a good steak in a long time and crave it very badly? The bafflement of this week’s Torah narrative, however, extends well beyond the brow-raising beef crisis. The broader Parsha narrative, it appears, is no less riddled with enigma and inconsistencies.

The state in which the Israelites are portrayed in our Parsha can best be described as “Upheaval.” In fact, so defiant are the Israelites reported to have become that they are found romanticizing over their good-old-days – savoring, of all things, their brutal Egyptian bondage – even as they bitterly lament their new impoverished diet and boring fare: “And thus the men complained, we remember the fish that we would eat in Egypt free of charge; and the cucumbers, melons, leeks, onions, and garlic. But now our life is parched, there is nothing; we have nothing to anticipate but the manna!” (Numbers 11:5-6).

This narrative appears to trigger a slew of perplexities. The claim about the “Free fish,” for example, seems entirely ludicrous as noted in the Talmud: “Since when was anything free in the land of slavery muses the Talmud. Even straw for bricks was not provided for them, how could they have possibly convinced themselves that they had free fish?”

Furthermore, what could they possibly have against the manna that faithfully rained down from heaven, day after day, in order to satiate and sustain them?

The manna, we are taught, not only provided necessary nutrition, it furthermore had the miraculous ability to transform into a palette of delicacies upon the mere whim of its consumer. How could anyone mock that?

Even more perplexing is Moshe’s reaction to all this. Whereas in other instances, which appear to have been far graver, such as the sin of the golden calf, he goes to bat on behalf of the Children of Israel, even at great risk to his own relationship with G-d, yet here he tends to lose his patience with them. Instead of defending them he appears to give up on them.

Most curious of all, though, is why the Torah would include this embarrassing episode as part of its narrative. The Torah is surely not in the habit of repeating Lashon Horah. Why is it important for us to know about the Israelites’ shameful and unbecoming conduct?

The answer is because therein lie pertinent psychological and sociological lessons for all of Israel and mankind for all of time. Indeed, critical Insights regarding the delicate and elusive nature of true contentment and meaningful fulfillment are contained herein.

The Talmud asserts that when the Israelites romanticized about the “Free” food that they enjoyed in the land of Egypt, they were actually alluding to something entirely different. They were lamenting the fact that in Egypt their food was entirely free from Divine commandments-Mitzvos, while now they were confined and restricted by G-dly rules and commands.

Rashi makes a similar assertion. In reference to the verse that states “Moshe heard the people weeping in their ‘Family’ groups.” Says Rashi: The issue of “Family” signifies the underlining reason for their complaints: “They were frustrated by family laws, i.e. non permissible sensual relations and adultery.”

So, while they spoke about fish and leeks and onions and garlic, their true frustration had nothing at all to do with that. While they may have convinced themselves that they missed the food that they never really ate in Egypt, something entirely different was actually going on.

Accordingly, the first lesson to be gleaned from the shameful events related in our Parsha is the identification of a novel human trait that precipitates inner-conflict, discontentment and rebellion.

The source of this destructive trait appears to be a distorted sense of reality. It is the product of an unhealthy emphasis and perverted recollection of one’s past, or the unrealistic expectations and exaggerated focus on the future.

The one thing that seems apparent about this debilitating syndrome is that it is not the result of any real or legitimate need. It is rather the consequence of an arbitrary and capricious wishfulness – wanting for the sake of wanting or just because it’s there, or at least we believe it’s there.

First it’s yesterday’s imaginary fish; then it’s the aroma of tomorrow’s irresistible meet, which in truth is none of the above but rather disguised devious desires.

This malady is arguably the result of a life too good and tranquil – a wistful dullness that is born out of not having any true wants or worries – not having enough Tzores (Heaven forbid) to contrast our abundant blessings.

This peculiar character trait, it appears, has yet to be explicitly identified in modern psychology. Even within Judaism it appears somewhat deficient of decisive definition.

The only direct Biblical mention of this phenomenon is in our Parsha. The unique word the Torah uses to describe the particular syndrome is “Misoninim.” It is the only time this word is found in the Torah. Yet the discontentment and disgruntlement that stems from the Misoninim affliction serves as a sure breeding ground for untold strife and upheaval.

There can be no better proof of this fact than Israel’s precipitous slide, beginning with their extraordinary self transformation, the most significant in human history – consummated by the historic Divine encounter at Mount Sinai – and ending with their tragic condemnation to the desert’s soil. This noteworthy phenomenon is further exacerbated by the fact that at the time of their tragic inversion things could not have been looking any better for them as a people.

Having just attained new majesty by virtue of their glorious national formation and tribal order, they have realized the pinnacle of nationhood. Encamped as they were around the Holy Sanctuary – each tribe proudly boasting a distinctive banner and flag – the conquest of the Promised Land was in clear view.

Indeed, with an army in place, Kohanim prepared to serve and Levites filled with song, they seemed perfectly poised for redemption. But then, as if out of nowhere, began the downward spiral; the swift deterioration that resulted in the condemnation of the entire generation that left Egypt.

They had only begun their remarkable career away from the abyss of Egypt into the spiritual crucible of the wilderness, where they accepted the privilege of Divine service and way of life, and they have already regressed. What happened and why?

It all began in “Chapter eleven” (pun intended) of our Parsha: “And the people took to seeking complaints.” It is fascinating that the Torah in this episode makes no attempt to ascribe any cause or reason for their complaints.

The Torah appears hereby to introduce the aforementioned destructive human characteristic. Some complaints are triggered by rational causes, though not necessarily legitimate, but others have no rational cause – Kvetching for the sake of Kvetching. The complainer is himself not sure as to why he’s complaining.

An amazing insight into the human psyche is herein contained: Just because we have it all doesn’t mean we have achieved happiness. No matter how good things may be it is human nature to get tired and seek something new and different – to get bored and complain.

When they left Egypt, the Jewish people had it all. At Mount Sinai they were inspired and invigorated as they declared: “We shall do and we shall hear!” They had great hope and great excitement. They had purpose and they had mission. But they lost direction. They were stricken by the Misoninim Syndrome and allowed themselves to lose it all.

The important lesson contained in this narrative is that Happiness and contentment are a skill unto themselves. They are not the result of the things we have but rather the things we learn. They are traits that must be developed and cultivated.

Our Parsha teaches us that to have it all is not necessarily to have it right. To have it right we must know how to hold on to the blessings and remain inspired. We must learn to derive inspiration from truth rather than from novelty and pleasure. We must likewise learn to live in the present rather than the past or future.

May we take to heart these poignant lessons of our Parsha and apply them well. By learning how to avoid falling prey to the “Kvetching Syndrome,” we will surely remain focused on our cosmic mission, which began with our birth as a nation upon our exodus from Egypt, and hasten thereby the era of Moshiach BBA .

1 Salvation!

Wonderful simply Nifla article! A mensch produces good out of the treasure of his heart…And a evil man out of the evil treasure in his heart brings forth that which is evil. For out of the abundance of the heart his mouth speaks. A attitude of Gratitude is what we all really need because Moshiach knows our heart. Shalom.

Truly admirable

Phenomenal. Let’s aim for true happiness.

S.m.k