Creating a Kosher Alternative to the Transcendental Meditation Deception

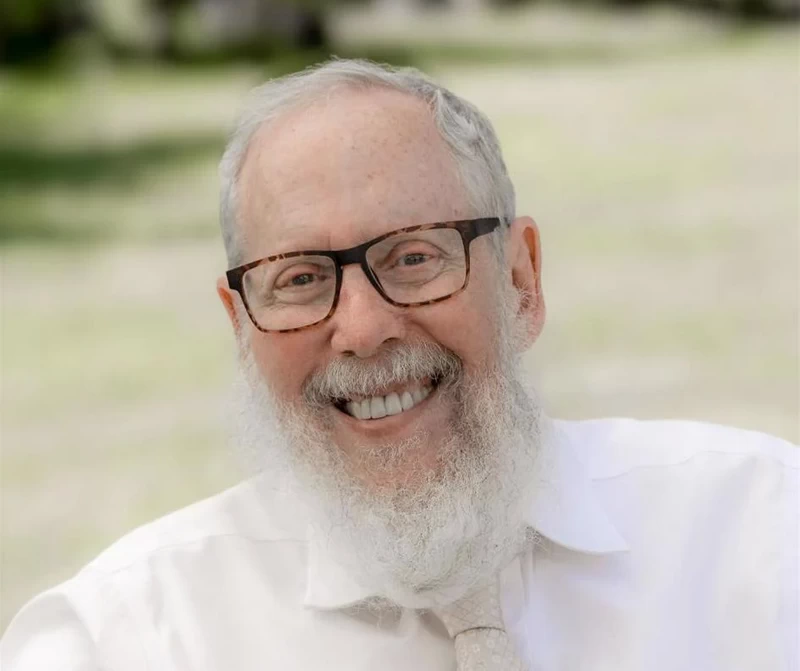

by Mendel Scheiner – chabad.org

In 1975, Aryeh and Tova Hinda Siegel were among the 1,500 people filling the Hollywood Palace Theater for a taping of “The Merv Griffin Show.” Applause shook the room. Hundreds leapt to their feet. All eyes were fixed on one man. On the stage sat a bearded Indian monk in a loose white robe. Merv Griffin, the television host, greeted him: “I welcome you to California, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi,” he said. “I have a feeling you have a few friends here.”

The monk sitting cross-legged on the stage was the founder and leader of the Transcendental Meditation (TM) movement, and his message was being beamed to millions of homes across America.

Transcendental Meditation first burst onto the scene in 1968, when the Beatles’ pilgrimage to the Maharishi’s ashram in India catapulted the practice into mainstream Western culture. Celebrities sought Eastern enlightenment, and others followed. “I’ll start off by saying I’m a meditator,” Griffin proudly admitted on stage.

This was an era when urban crime, violent riots and the Vietnam War had seemingly eaten up the post-World War II promise of peace. Vulnerable youth were already eager for healing, the celebrity endorsements only drawing them in more. Everyone seemed to be searching for inner peace; if you weren’t, you were missing out.

On his U.S. tour, the Maharishi made frequent television appearances. Calm and cheerful, he offered millions of viewers a simple solution to their angst: learn TM. His appearance on “The Merv Griffin Show” that October day in 1975 brought him an estimated 300,000 new adherents.

In their search for meaning, many tens of thousands of Jews were attracted to TM. Long before Chabad.org or online Torah study existed, Jewish education and spiritual resources were harder to come by. “About 30% of the sign-ups were Jewish,” Siegel recalls. “A startlingly disproportionate number.” At 50,000, Israel had the highest number of TM practitioners per capita.

The organization claimed to be secular and would enhance one’s existing religion, yet at its core, it peddled Hindu worship. This lie enabled TM to penetrate corporations and schools, masquerading as secular psychology.

“How has your trip gone so far?” asked Griffin on the show. Grinning, the Maharishi replied, “I have been very satisfied with the response of the people to this dawn of the age of enlightenment.”

A Plague Not Listed in the Torah

Aryeh Siegel grew up like many Jewish kids in America. “We went to Hebrew school and resented it,” he says. “I didn’t want to be there; I wanted to play baseball. You went because you had to, and after your bar mitzvah, it was over.”

Born on the north side of Chicago, Siegel, then known as Larry, attended public schools. Idealistic and determined, he wanted to heal the world. As an undergraduate, he studied sociology and earned a master’s degree in both social work and public health, the latter at the University of California, Berkeley. He eventually took a research position there as well.

Around 1971, when his best friend described TM as a new trick for stress relief, Siegel decided to give it a shot. “I paid $35 for the course,” he recalls. It was an introduction to TM. Later, the price rose to $2,500.

TM’s initiation, or Puja ceremony, presented as a “ceremony of thanksgiving,” was actually Hindu worship. Participants brought flowers, fruit, and a white cloth, innocently participating in rituals whose hidden purpose was to connect their souls to the guru. TM claimed the mantras were meaningless sounds; in truth, mantras are names of Hindu gods.

Aryeh became deeply entrenched in Transcendental Meditation. “The practice offered a spirituality I found deeply attractive, because I lacked a strong Jewish spiritual background,” Siegel says. In 1974 he began working at the Maharishi’s national headquarters in Los Angeles, where he met his future wife, Tova Hinda, herself involved with TM since 1970. They married in 1975, about three weeks before attending “The Merv Griffin Show’s” TM special. Later, the two of them spent six months studying with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, training to become TM teachers. “I believed it could bring ‘world peace,’ a vision that appealed to my social-work ideals.”

Their training involved meditating up to eight hours a day and studying Hindu scriptures. Siegel, with his academic background in public health and behavioral science, rose swiftly through the ranks. “Because of my background in academia, I was frequently asked to teach important students, including astronaut Buzz Aldrin,” he recalls. The couple became senior members of the World Plan Executive Council, TM’s governing body. Siegel’s official titles included director of the Institute for Social Rehabilitation and Director of Research.

Though the couple did not know it at the time, the rapidly growing popularity of this movement of idol worship preying on vulnerable Jewish hearts and minds didn’t escape the attention of the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory.

Concerned about TM’s influence, the Rebbe sent a confidential letter to mental-health professionals, warning that Jewish youth and adults were seeking calm in “foreign cults” and urging the creation of a halachically sound alternative.

In July 1979 (13 Tammuz, 5739), the Rebbe issued a passionate public warning (a written synopsis is available here.):

“It is a plague not even listed in the Torah, which has spread in this country and in others … ,” he said, identifying Transcendental Meditation by name. “It is pure idol worship.”

TM peaked, and then eventually plateaued. The once-wide-open meditation market in the West was now crowded. Celebrity endorsements lost their shine, and users waited for enlightenment that never arrived. Desperate for an edge, TM launched the TM-Sidhis program, promising paying customers superpowers such as levitation and invisibility.

By 1976-77 the Siegels were growing skeptical. “I became disillusioned with TM’s scientific claims,” he says. The supporting research, he started to realize, was riddled with bias, poor sampling, and non-randomized groups. TM teachers had no clinical training and were unqualified to handle students with serious mental-health issues. The standard response to distress was simply: “Keep meditating.”

Wanting to improve the quality of TM research, naive and still hopeful, Siegel was accepted into a Ph.D. program in behavioral science research at UCLA.

“I used to bring home the UCLA student newspaper every afternoon,” he recalls. Tova Hinda was once leafing through it when she noticed an ad for a class, “Learn more Hebrew in 11 weeks than you have in 11 years of Hebrew school.” Intrigued, she enrolled.

At that point, the Siegels had decided that their children should receive a Jewish education. Aryeh, with a very deficient Jewish background, and his wife, with a Conservative one, first enrolled their kids in a Reform Hebrew school. The couple was unsatisfied and pulled them out, seeking a stronger foundation.

When Tova Hinda returned home from the Hebrew class, Aryeh asked, “So how was it?” She replied, “It was really good. I think this rabbi actually believes in G‑d.” That rabbi was Shlomo (“Schwartzie”) Schwartz of UCLA’s Chabad House on Gayley Avenue, just a block and a half from the TM center where the Siegels worked.

The couple quickly formed a close connection with Schwartz. “We hit it off immediately,” Siegel recalls. “When he asked what I was studying and I said, ‘Hindu scriptures,’ he replied, ‘Let’s learn together. I’ll bring a book of mine, and we can compare.’”

The book Rabbi Schwartz brought was Tanya, the foundational work of Chabad Chassidism authored by Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, known as the Alter Rebbe. For two years, Schwartz visited the Siegel home once or twice a week from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m. to study Tanya with them and discuss Jewish theology.

“I immediately found Tanya profoundly deeper than what I’d been studying,” Siegel remembers.

In 1979, the Siegels left TM, Aryeh dropping out of the Ph.D. program after realizing TM’s primary interest in research was marketing. Siegel then flew with Schwartz to New York to meet the Rebbe.

In the upstairs synagogue in Chabad World Headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway, Siegel joined Schwartz in praying the mincha afternoon service together with the Rebbe. Afterward, they waited outside for the Rebbe to walk by. As the Rebbe walked out of the synagogue, he turned to Siegel. Eyes locked, the Rebbe smiled, wishing him a good new month.

Unknown to Siegel, the Rebbe had given a passionate talk about meditation just six months earlier. At that moment, Siegel was still meditating for four hours a day.

When Rabbi Moshe Ben Tov, a renowned kabbalist and sofer [scribe] from Israel, visited Los Angeles soon thereafter, the Siegels had all of their mezuzahs inspected.

The kabbalist quietly examined the parchments. Looking up, he muttered the only two English words of that encounter, “Transcendental Meditation.” Through his interpreter, he told Siegel that his soul was confused and he had to choose a path. “That morning was the last time I practiced TM,” Siegel recalls. Ben Tov then instructed him to destroy all items related to idol worship in the home. Tova Hinda agreed, admitting she had mostly fallen asleep during the meditations anyway. That afternoon, the Siegels burned every foreign spiritual item in the house.

After leaving TM, Siegel directed a mental health center, served as an executive at the Jewish Federation of Los Angeles, and later became a real estate broker. The family grew close to Rabbi Avraham Levitansky of Chabad of S. Monica, enrolling their children in his Hebrew school.

“Rabbi Schwartz recommended we send our kids there, and they loved it,” Siegel says. “He was really a wonderful person.” The family was active in their Chabad community and the Machne Israel Development Fund, with periodic private audiences with the Rebbe.

“For decades, I had no contact with TM. I didn’t even know Maharishi had died in 2008,” Siegel says.

Everything changed in 2015.

The Resurgence

He was reading a book about the Rebbe when the word “meditation” caught his eye. The book described a circa 1962 episode where the Rebbe had annotated a paper on Hindu meditation, crossing out idolatrous parts and suggesting alternatives. He sent it to Rabbi Dr. Abraham Twerski, urging the creation of a “kosher way to meditate.”

Then, Siegel read, in 1978 the Rebbe sent a memorandum to some 50 mental-health specialists. Concerned that some might misinterpret the memo, in which the Rebbe stated that meditation could have therapeutic value in relieving “mental stress,” he marked it “highly confidential.” In the memo, the Rebbe underlined that rabbis had rightly banned various meditation movements as they all involved foreign religious rites and rituals, but as some might benefit from their therapeutic aspects, there ought to be a way to offer those who need such treatment a kosher alternative “utterly devoid of any ritual implications.”

(Elsewhere, the Rebbe underlined that even kosher meditation “should only be used by those who need it” for medical purposes, and that it could have a negative effect on those who don’t.)

Siegel was astounded. “This was remarkable,” he says. “The Rebbe, in 1962, advocated for kosher meditation years before the whole movement had even reached the U.S.” Further research revealed that Dr. Yehuda Landes of Palo Alto, Calif., had corresponded with the Rebbe to develop a kosher meditation framework. The plan included centers with modalities such as breathing exercises, bodily postures, nutrition, soulful music, social gathering in the spirit of a farbrengen, a hot mikvah and meditation on Chassidic ideas. The Rebbe twice even offered seed money. Dr. Landes approached at least one pertinent Jewish organization with the proposal, but it deemed the idea too “hocus pocus” and too expensive to implement.

“At the time that I was seeing this letter in 2015, I thought TM was dead, but suddenly TM was everywhere again,” Siegel recalls. Celebrities were once again promoting it. Most concerning, the David Lynch Foundation had announced plans to teach TM to 1 million public-school students.

After the Maharishi died, it emerged that he had transferred his multibillion-dollar estate to his family in India, nearly bankrupting his movement’s U.S. centers. The organization planned a resurgence, targeting schools and veterans. “Seeing all this, I knew I had the tools to fight it,” Siegel says. He closed his business and wrote his first book, Transcendental Deception, to expose the cult.

Reading his book, a Christian teacher in Chicago contacted him after discovering TM at her school. At a public Board of Education meeting, the teacher brought a 14-year-old girl, her student, who nervously addressed the board: “One day, a man I had never met took me to a classroom alone, with shades on all the windows, and sang foreign words in front of a picture of a smiling Indian man while throwing rice and bowing to the picture. He told me not to tell my parents what he said. I don’t know what he was doing, but I did know it was not the religion we practice at home.” The room was stunned.

There was a reporter from the Chicago Tribune covering the meeting, and a week later, a front-page story was published on Eastern religions seeping into American public schools.

When the Board of Education forbade the Puja ceremony, the David Lynch Foundation abandoned the program that had already impacted more than 3,000 students across seven schools.

Soon after this groundbreaking testimony, Siegel received a call from a lawyer, “Hey, is this Aryeh Siegel? I read your book, and I saw what happened. I think we are going to sue.” He did.

Subsequently, three plaintiffs were identified. One case was settled for an undisclosed amount; a second student was awarded a judgment of $150,000; and a third case was certified as a class action and settled for $2.6 million. Siegel sees Divine Providence in the fact that the judge signed the certification order on the Rebbe’s birthday. “After this case, it is unlikely that insurers would provide liability insurance to the Lynch Foundation, effectively ending their public-school expansion program,” Siegel says.

A Kosher Kind of Calm

As Siegel delved deeper into the Rebbe’s writings on the subject, he realized that many people had never heard about the Rebbe’s strong interest in the development of a form of kosher meditation. Wanting to share this information, he wrote an article for Compass Magazine titled “The Rebbe’s Call for Kosher Meditation.”

After reading Siegel’s story, Rabbi Levi Y. Raskin in London sent Compass three previously unknown letters from the Rebbe addressing the subject. Word began to spread. Siegel was invited to present twice at the International Conference of Chabad-Lubavitch Emissaries, where he shared his story and explored the Rebbe’s vision for meditation.

Following one of those talks, Rabbi Berel Bell of Montreal reached out. He explained how he had begun fielding questions from Jews about meditation and wanted to revisit the Rebbe’s approach.

The response led Siegel to begin his second book, Kosher Calm, a guide to meditation according to the Rebbe’s guidelines. He has since authored a well received article on Chabad.org, “Kosher Meditation: A Jewish Path to Peace of Mind,” and been interviewed by Chana Weisberg.

“The Rebbe had always been an activist in the mental health world,” says Siegel. “Early on, he understood the profound benefits of positive thinking and the power of belief to engage the mind in healing.” For those who need it, Siegel’s book is a how-to guide to kosher meditation, along with an explanation of the science behind it.

Says Siegel, the Rebbe’s approach to meditation was not about escaping reality. Instead, the goal is to focus one’s abilities and energies on creating a dwelling place for G‑d on Earth, and “ultimately welcoming the arrival of Moshiach.”

For more information about Aryeh Siegel’s work, visit KosherCalm.org or purchase his book: Kosher Calm.

Buford

Why are these pictures of an idolater on this website?