How the First Grand Public Menorah Was Born in San Francisco, 1975

by Menachem Posner – chabad.org

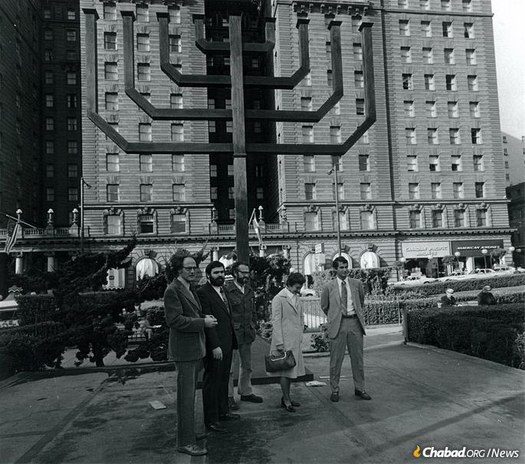

On a blustery first night of Chanukah in 1975, more than 1,000 Jews crowded into San Francisco’s Union Square to witness the first giant public menorah-lighting in modern history.

Forty-four years after this unprecedented show of Jewish pride and observance, some 15,000 large public menorahs will bring light to public squares, government buildings, sports arenas and other high-profile venues in more than 100 countries around the world. Thousands more menorah-topped cars are expected on the roads this year.

As detailed by Rabbi Dovid Eliezrie in The Secret of Chabad, the original giant menorah lighting was the brainchild of Rabbi Chaim Itche Drizin, who arrived as a Chabad-Lubavitch emissary to the Bay Area in 1971. As director of Chabad in Northern California, Drizin established the Chabad House in Berkeley, Calif., and then the first Chabad presence in San Francisco. Together with Rabbi Yosef Langer, he had made significant headway, but they knew there was more to be done.

After four years of working in the community, the rabbis were looking for ways to promote Jewish identity and pride. So Drizin brainstormed with his friend, Zev Putterman, program director at KQED, a local public-television station. The year before, the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—had called for a campaign to promote Chanukah observance. “Why not a menorah in Union Square?” posed Drizin. “Chanukah is a holiday when we are supposed to publicize the miracle that happened thousands of years ago. It fits.”

Putterman agreed and suggested they propose the idea to his old friend Bill Graham, a rock impresario and legendary concert promoter for artists such as Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, the Who and the Grateful Dead. Graham, born to a Russian-Jewish family in Berlin in 1931, survived the Holocaust but lost his mother and a sister in the Nazi German gas chambers—another sister starved to death attempting to escape together with him—before making it to New York where he was fostered by a Jewish family in the Bronx.

Sitting in Graham’s Mission District office, Drizin and Putterman pitched their menorah idea. Graham, a born pioneer, immediately embraced the concept. He also had the political connections, the financial resources and the craftsmen who built his famous show sets who could construct this grand menorah.

The idea wasn’t exactly a new one.

A year earlier, in 1974, Rabbi Avrohom Shemtov, the senior Chabad emissary in Philadelphia, lit a small wooden menorah near the Liberty Bell in the city’s center with the help of yeshivah students, who built it from scratch.

At the same time, Chabad of California installed a 16-foot menorah in front of its Los Angeles headquarters in Brentwood. That menorah, the West Coast’s first, was a rough affair made of commercial construction materials and built by Shaul Eisen, who grew up in the Bobov Chassidic community in Brooklyn and was then living at the L.A. Chabad House, helping with various Chabad projects.

But what the San Francisco rabbi and rock promoter were cooking up was something new: a 25-foot mahogany menorah parked smack in the capital of America’s counter-culture. To oversee their unprecedented construction project, Drizin asked Eisen, who has a knack for engineering and construction, to hitch a ride to San Francisco to collaborate with Graham’s team.

“I would arrive at the shop every day around 12,” recalls Eisen, now a retired contractor in Brooklyn, N.Y., “and everyone would stop what they were doing and get busy with the menorah. Welders, carpenters, they all had a part. We had to have a lot of custom parts and fittings made, so everyone was involved. The result was beautiful, all wood besides for a steel core, finished in beautiful mahogany. It weighs 3,500 lbs.”

Location, Location, Location

Drizin would have been happy if 100 people showed up for the menorah lighting. Instead, more than 1,000 people came out to watch the spectacle of Jewish pride. The media was all over the story. Chanukah, for the first time, was big news in San Francisco.

Then a local Reform rabbi launched a public campaign denouncing Chabad’s newest project. On the pages of The San Francisco Examiner, he chastised the menorah-lighting. He also lambasted the local Jewish Federation for supporting Drizin. He contended that they had shattered one of the sacred principles of modern Jewish life by “eroding the separation of church and state.”

The menorah debate in San Francisco climbed onto the national stage, with the controversy soon becoming the talk of the Jewish community across the country. After the holiday, Jewish Federation leaders asked Drizin to a meeting. Stung by the criticism, they told Drizin that next year, it should not be held at Union Square.

The Federation leaders suggested that next year the menorah instead be placed in the Stonestown Shopping Mall in San Francisco’s Sunset District. It was private property, they said, and so no one could claim any constitutional issues. They even agreed to help him if he would just move it off public property.

“What happens if no one comes?” Drizin asked. “Union Square is unique; it’s in the center of downtown.” They promised that if the new venue proved unsuccessful, then they would not oppose his return to Union Square the following year.

Drizin was perplexed; shaped by years of battle against the Soviets in Russia—his father, Rabbi Avraham Mayor, was a famed figure in Chabad’s Soviet underground who spent years on the run from the secret police—from a young age he had been taught not to retreat in the face of pressure. He asked the Rebbe for guidance. The Rebbe advised him to seek counsel from someone there with a good understanding of the situation in San Francisco.

At the time, Rabbi Mendel Futerfus was visiting the Bay Area on one of his annual fundraising trips. Known simply as “Reb Mendel,” Futerfas was a renowned Chassidic elder who was himself no stranger to Soviet persecution. After helping to organize the 1946 escape from the Soviet Union of a large part of Russia’s Chassidic community, Futerfas was arrested by Soviet authorities in 1947 and ultimately served 9 years in Stalin’s infamous Gulag labor camps. A few years after finishing his sentence, in 1962, intercession from overseas finally secured permission for him to join his family in the West. Once a year, he would come to California to raise money in order to secretly ship food packages behind the Iron Curtain. A grizzly man full of energy, deep compassion and piety, he was a figure who commanded great respect.

“What should I do?” Drizin asked the venerable Chassid.

“If the shopping center doesn’t work, will they keep their word and let you return to Union Square?” asked Reb Mendel.

“Yes,” replied Drizin.

And then, using one of his famous parables, Reb Mendel said: “Before a bull charges, he takes a step back, gathers his strength and roars forward. Take the compromise, and if it doesn’t work, return to Union Square.”

Drizin informed the Federation that he would move the menorah. As he suspected, the new location didn’t draw much of a crowd the following year. So Drizin decided to move the menorah back to Union Square. As had been agreed upon, public opposition was dropped in the wake of the unsuccessful lighting in the shopping center. Since then, the menorah-lighting has turned into an annual—and wildly successful—Chanukah Festival, drawing tens of thousands to Union Square and becoming a part of San Francisco culture (it was renamed the Bill Graham Menorah Project after Graham passed away in a helicopter accident in 1991).

Encouraged by the Rebbe, the idea soon caught on around the world.

Menorahs Take Root Everywhere

These successes were not without backlash. As menorahs popped up in a growing number of American cities and towns during the 1980s and 1990s, so, too, did the opposition.

When the opposing organizations failed to convince the Chabad emissaries to remove the menorahs from the public square, they took varying strategies: lobbying government officials to deny permits; challenging the efforts in the media; taking Chabad to court; and supporting lawsuits that were launched in some communities by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Many of the court battles—one even reached all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court—were championed by Washington D.C.-based attorney Nathan Lewin, who today still takes a personal interest in those public menorahs threatened by unwelcoming vigilantes or jittery public officials.

It was the Rebbe who highlighted that the menorah and what it symbolized, far from being antithetical to American public life, was in fact a part of its fabric. In a 1982 response to a Jewish leader in Teaneck, N.J., the Rebbe wrote that the public menorah display had served as an inspiration to countless Jews and “evoked in them a spirit of identity with their Jewish people and the Jewish way of life. To many others, it has brought a sense of pride in their [Jewish identity] and the realization that there is no reason really in this free country to hide one’s Jewishness, as if it were contrary or inimical to American life and culture. On the contrary, it is fully in keeping with the American national slogan ‘e pluribus unum’ and the fact that American culture has been enriched by the thriving ethnic cultures which contributed very much, each in its own way, to American life both materially and spiritually.”

Public menorah-lightings have become indeed part of the national culture. In Washington, the menorah is placed by American Friends of Lubavitch (Chabad) on the Ellipse opposite the White House. President Jimmy Carter attended the lighting the first year it was erected in 1979 after emerging for the first time from a self-imposed seclusion in the White House prompted by the Iranian hostage crisis. President Ronald Reagan offered another significant moment in history by naming it the National Menorah.

Since then, noteworthy public officials from both political parties, from Vice President Joe Biden and former White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel to Bush-era Attorney General Michael Mukasey and President Trump’s economic advisor Gary Cohn have participated in the lighting. Chanukah now has a place of prominence in the White House itself. President George W. Bush was the first to host an annual White House Chanukah party, a tradition carried on by President Barack Obama, and now by President Donald Trump. American Friends of Lubavitch’s Rabbi Levi Shemtov even supervises the koshering of the White House kitchen for the festivities.

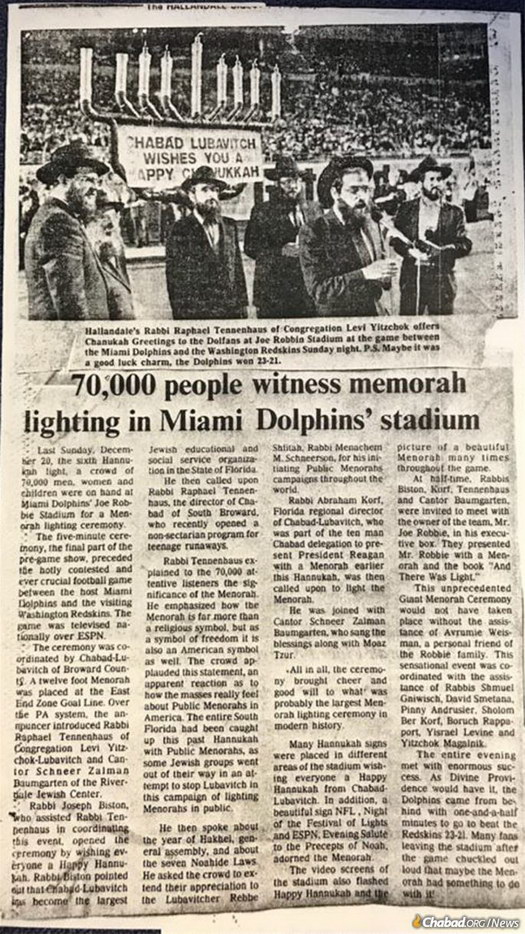

Across the country, menorahs are now commonplace in shopping malls and public squares, statehouses and city halls, airports and train stations, even individual stores. Theme parks have even gotten into the Chanukah spirit: Universal Studios started a menorah celebration in conjunction with Chabad on the famed Universal CityWalk near Hollywood, Calif. And in 1987, at what was then Joe Robbie Stadium in South Florida, Chabad Rabbi Raphael Tennenhaus of Chabad of South Broward in Hallandale, Fla., lit a menorah during halftime at a Miami Dolphins game, starting a new trend of menorahs in the arenas, fields and stadiums of professional sports teams.

Back in San Francisco, the Bill Graham Menorah in Union Square has become a local tradition. This year Dec. 22 was proclaimed Bill Graham Menorah Day in San Francisco, and the event included a full slate of activities, from kids’ crafts to kosher deli for the adults. The headliner is of course the kindling of the mahogany menorah, which has been led for decades by Langer, now director of Chabad of San Francisco. The menorah is then lit each night of Chanukah.

Looking back at sea change that took place over the past four decades, Drizin says that at the time, he had no idea of the larger (and lasting) significance of his actions. “I was simply thinking, like any shliach, what can I do to uplift my city and create a kiddush Hashem?” he recalls.

One of the strongest indicators of success is the fact that the concept—once derided and even ridiculed—has now been adopted by many of the very organizations that resisted it most. Poetically, for the past few years, the temple of the San Francisco rabbi who first opposed the idea has been holding its very own public menorah-lighting.

“Personally, I have a lot of inner nachas because I know how it started and the magnitude of what it has become—a world Jewish tradition,” says Drizin. “It is a world lit up.”

To learn about the history of legal battles for menorahs in public places, click here.

Much of this article was adapted from a chapter of The Secret of Chabad by Rabbi David Eliezrie, which chronicles the events, philosophies and personalities that have made Chabad-Lubavitch a worldwide phenomenon.

Decades later, the giant menorah lighting still draws a crowd (photo: www.billgrahammenorah.org)