‘Literary Pioneer’ Expanded Chabad’s Profile in Post-War Israel

Rabbi Avrohom Chanoch Glitzenshtein, a noted scholar and longtime administrator of Chabad institutions in Israel who passed away March 11 in Jerusalem at the age of 86 was remembered as Chabad’s “literary pioneer,” who over the course of many years compiled, translated and edited some 60 volumes on Chassidic thought, history and lore, and was lauded as a key figure in the institutional growth of Chabad in Israel.

Glitzenshtein’s longtime friend and colleague, Rabbi Tuvia Blau, mourned him as an activist who was at once innovative and unassuming. “He was the first to confidently take the initiative to widely disseminate the teachings of the Rebbe[Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory]. He was the first to build relationships with journalists and to translate the Rebbe’s words into Hebrew. … He was the secretary of the Yeshivah [in Lod], which was the center of the Rebbe’s activities in the Holy Land. … In many different areas, the Rebbe made him responsible and placed his trust in him. He did everything quietly and modestly … yet in the early years, he was the only one who achieved anything.”

Glitzenshtein was born on Jan. 7, 1929, to Rabbi Shimon and Esther Eidel Gelizenshtein. He grew up in Jerusalem, where his father was a prominent and well-connected scholar, writer and communal figure. Shimon Gelizenshtein traveled to study at Yeshivah Torat Emet in Hebron shortly after it was first established by Rabbi Shalom DovBer Schneersohn, the fifth Rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch, circa 1912.

During World War I, he found himself in London, where he served as secretary to Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, who later became the first Chief Rabbi of the Holy Land. He subsequently returned to the Holy Land, where he married and served as secretary of Torat Emet, which was re-established in Jerusalem, until the end of his life.

Though Avrohom Chanoch would have been too young to remember it, just a few months following his birth, the Chabad community in the Holy Land hosted the historic visit of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, the fifth Rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch. Rabbi Shimon penned and published an authoritative account of the visit to ensure that the “impressions seared deep into the heart will not ever be erased.” He also published monographs on the lives of the first two rebbes of Chabad, and contributed occasional articles to various journals and newspapers. Avrohom Chanoch later commented that it was his father’s talent and example that set him on his own path as a writer.

A Guiding Directive

As a child, Glitzenshtein was educated in the famous Etz Chaim Yeshivah in Jerusalem before moving in his teens to study at Torat Emet. In 1949, he was appointed secretary of the Chabad Yeshivah in Lod and received a letter from Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak giving him specific instructions as to how he should discharge his duties: “Know that good order in the work of an institution is one of the foundations of its continuity and success … and the preservation of order in an institution is very much dependent on the diligent work of its secretary. May G-d be at your aid in your communal work, and strengthen your health and make you successful in what you require in personal matters … .”

The letter was dated the 20th of Kislev. Just 50 days later, on the 10th of Shevat, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak passed away. Glitzenshtein would later say that he took this letter as the guiding directive of his entire life. From this point on, he dedicated himself to the orderly and diligent expansion of Chabad’s institutional, communal and scholarly activities. Though not even 20 years old and yet unmarried, he quickly became one of the effective representatives of Chabad in the Holy Land.

A Lifelong Project

After the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—succeeded his father-in-law as the seventh leader of Chabad, Glitzenshtein began to write to him regularly, reporting on his work, and seeking advice and instruction. In one early letter, the Rebbe wrote that he was “exceedingly gratified” to see Glitzenshtein’s article “in the pages of Hamodia [the Hebrew-language daily newspaper printed in Jerusalem] about the teachings of the Baal Shem Tov and the celebration of Yud Tes Kislev.” In a recent interview, Glitzenshtein recalled that he had begun to write similar articles on Chabad thought, history and activities almost as soon as Israel was established. The Rebbe asked him to send him copies of any future articles and advised him to facilitate the publication of similar articles in the Israeli national press.

In the same letter, the Rebbe proposed that Glitzenshtein embark on a new project. “Since G-d has bequeathed you with a writer’s pen,” he wrote, “perhaps you will take upon yourself to translate into clear Hebrew everything related about the Alter Rebbe, and similarly about the Mitteler Rebbe, and similarly about the Tzemach Tzedek, which are recorded in the talks of my father-in-law, the Rebbe of righteous memory … .” The Rebbe also asked him to estimate the time it would take him and the compensation he would require, and advised him to provide the source for each quotation.

While Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s letter had set him on the course of institutional and communal work, the Rebbe’s letter triggered a lifelong project of personal research, scholarship and writing. Ultimately, he would compile and translate an authoritative series on the lives of the Baal Shem Tov, the Maggid of Mezritch, and the first six Rebbes of Chabad, filling a total of 15 volumes. Following the Rebbe’s directive, he sifted through the many traditions preserved in the writings and oral talks of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, organized them chronologically and thematically, and translated them from Yiddish to Hebrew.

This was more a literary, documentary and educational endeavor than a historical one, and wherever he encountered conflicting accounts, the Rebbe directed him to simply point out the conflict without attempting to evaluate which account was most correct. The nature of Glitzenshtein’s task was not simply to collect information or to tell stories, but to faithfully preserve the internal memory of the movement as it had been transmitted by the rebbes of Chabad exclusively—the internal vision of what Chabad was and what Chabad should be. From this perspective, every iteration of an anecdote carries relevant insight and is directly applicable to the continuing life of Chabad, both on individual and collective levels.

While he began working on this project in 1952, the first volume didn’t appear until 1960. As more and more material became available, Glitzenshtein continued to revise and expand his work, publishing the final updated editions in 1986.

In the summer of 1952, Glitzenshtein married Gittah Tovah, the daughter of Rabbi Avraham Pariz, himself a legendary pillar of the Chabad community in the Holy Land. Like her husband, she dedicated herself to the communal and institutional expansion of Chabad, and became one of the most active leaders of Chabad Women’s Organization in Israel.

Literary Endeavors Gain Recognition

Following his marriage, Glitzenshtein continued to expand his literary activities and started to become recognized as an authority on Chabad literature. One of the publishing projects that he pioneered was a new periodical, Biton Chabad, which included short articles on Chabad thought and history; recent talks from the Rebbe; and reports on current events and developments in the world of Chabad.

It was around this time that Eliezer Steinman, a prominent Israeli writer, began taking greater interest in Chassidism. After publishing a volume on the writings of Rabbi Nachman of Breslav in 1951, he turned his attention to other Chassidic figures and groups, including Chabad.

Steinman asked Zalman Shazar, who was known to be a good friend of Chabad, for help. Shazar, who later became president of Israel, hailed from a Chabad background, and was both a writer and a scholar in his own right. He turned to the well-known Chabad personality Rabbi Pinchas (Pinye) Althoiz, who set Glitzenshtein to work as Steinman’s assistant. Steinman went on to publish a total of six volumes on the Chassidic movement, including two on Chabad. He also wrote several articles on Chabad in the popular press and began a personal correspondence with the Rebbe. Other prominent writers who Glitzenshtein befriended included Nathan Alterman and Aharon Megged.

Over the course of more than four decades, Glitzenshtein received many hundreds of personal letters, messages and instructions from the Rebbe. These communications covered all aspects of his work on behalf of the Rebbe directly, on behalf of Chabad institutions, and on his personal work as a writer, translator and publisher. He played a pivotal role in episodes great and small, and on several unique occasions merited displays of particular affection on the part of the Rebbe.

One of the smaller but more iconic episodes occurred in 1959, when Glitzenshtein first traveled to New York to meet the Rebbe. Along with other guests, he was invited to participate in the Rebbe’s festive meal on the second night of Sukkot, and in the middle of the meal the Rebbe asked him to sing a Chassidic melody.

Just a year earlier, the Rebbe had delivered a landmark talk expressing his vision to bring Judaism to every corner of the globe, dwelling on the biblical verse beginning with the word Uforatztah, “You shall burst forth to the west and the east, to the north and the south.” Chassidim in Israel had set the verse to a lively Chabad dance tune, and without thinking, Glitzenshtein began to sing this new combination, rather than a more traditional melody. The next day, the Rebbe held a public gathering where he called upon Glitzenshtein “to teachUforatztah as it is sung in Land of Israel” to the assembled crowd.

Today, that song remains one of the most recognizable symbols of the Rebbe’s global revolution.

Glitzenshtein was one of the first of a new generation of Chabad activists in the Holy Land to cultivate relationships with public intellectuals and politicians. But his unassuming manner made it clear that his goal was purely to further Chabad’s institutional causes, and to disseminate Chabad teachings and publications to the wider public.

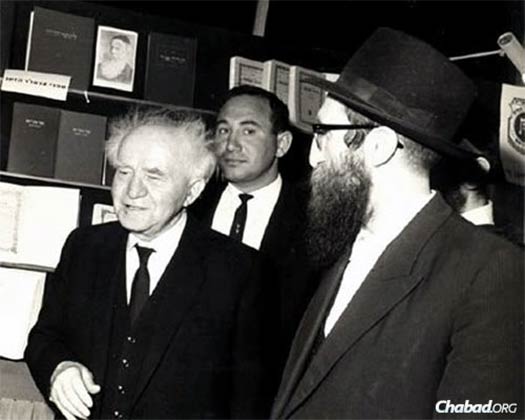

At the Rebbe’s request, he also encouraged many scholars and writers to send copies of their own publications to the Central Chabad Library in New York. During the 1960s and `70s, he used the Jerusalem International Book Fair as an opportunity to showcase Chabad publications. Among those who stopped by to examine his offerings was none other than former Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion.

Shazar had a particular interest in Chabad history, thought and bibliography, and made it his business to bring newly discovered manuscripts to the Rebbe’s attention. Glitzenshtein became a key liaison, who not only passed information and manuscripts between Israel and New York, but also took an active role in finding manuscripts, examining their content and preparing them for print. Shazar’s initiative and Glitzenshtein’s agency proved the seminal forces behind the ultimate publication of the oral discourses of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, a series that today runs to more than 20 volumes.

When Shazar presented Glitzenshtein with one of his scholarly publications, he addressed it to “the trusted custodian of Chabad treasures in Israel.”

Leadership and Legacy

When Glitzenshtein’s father passed away in the spring of 1963, the Rebbe directed that Glitzenshtein be appointed secretary of Torat Emet in his father’s place. In 1971, the Rebbe then charged that he be appointed to the leadership of the Chabad educational institutions for girls in Jerusalem, Beit Chana. The rabbi continued to play an active role in all manner of communal affairs, serving on the board of Chabad’s umbrella organization in Israel, Agudat Chassidei Chabad, until the end of his life.

The 1980s saw Glitzenshtein publish Hebrew translations of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn’s Yiddish talks and also a Hebrew edition of Lessons inTanya, the popular commentary by Rabbi Yosef Weinberg, in nine volumes. With the 1990s came a new series of Chassidic tales told by the successive Chabad Rebbes. The last few volumes drew from other sources, too, and the series now comprises 18 volumes.

Glitzenshtein’s publications have remained enduringly popular—classical foundations of any Chabad library. Both pioneering and prolific, he also paved the way for many other members of the Chabad community to take up the writer’s pen. Today’s blooming literary industry is a lasting credit to his vision.

In addition to his wife, Gittah Tovah, he is survived by a daughter, Rivkah Baila Veisfish of Jerusalem.

no one special

“During World War I, he found himself in London, where he served as secretary to Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook,”

World War 1 was over in 1918!!! This man worked prior to his birth???