Four Decades of Car Menorahs Lighting the Way

From Chabad.org by Dovid Margolin:

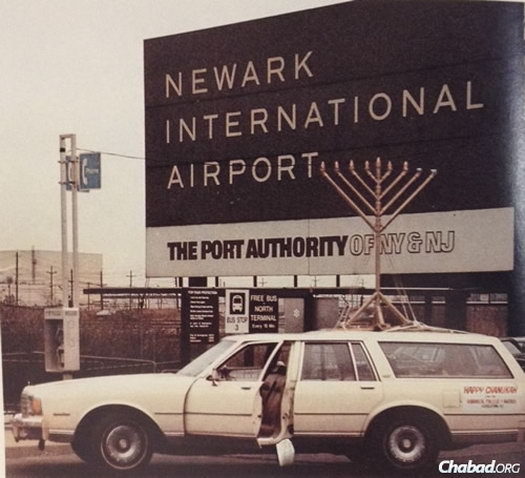

You know them when you see them, and when you see them, you know it’s Chanukah. The car menorah is a uniquely American innovation—a marketing gimmick created by young yeshivah students in the early 1970s as a way to spread awareness and the message of the eight-day Jewish holiday. Today, they can be found across the globe and on all kinds of vehicles.

Along with the giant public menorah displays that have become synonymous with Chabad-Lubavitch, these almost accidental inventions have revolutionized the way Jews celebrate Chanukah everywhere.

It was 1973, and the Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—had just a few years earlier announced his Chanukah-awareness campaign, encouraging his followers and emissaries to reach out to their fellow Jews and give them the opportunity to kindle the Chanukah lights.

Rabbinical students, newlywed couples and veteran rabbis jumped at the chance to disperse throughout their respective communities each year, knocking on doors and standing on sidewalks to distribute holiday fliers and portable menorah kits.

At the time, Shmuel Lipsker was a student at the Central LubavitchYeshiva at Lubavitch World Headquarters, at 770 Eastern Parkway in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y. As he and his friends prepared to head back to their regular Chanukah spot—the corner of Fifth Avenue and 47th Street in Midtown Manhattan—the boys tried to think of something that might grab the attention of the thousands of New Yorkers who would be rushing by them over the course of the holiday.

“We decided we’d build a large menorah and bring it with us,” recalls Lipsker.

His father, Rabbi Yaakov Lipsker, was a respected Chassid who was also a talented carpenter; in fact, the large and intricately inlaid wooden ark in the main synagogue at 770 is his handiwork. “My father had a lot of building material in the basement,” explains his son, “so there was enough wood for us to play with. We went down there and built a simple wooden menorah out of two-by-fours with a cinder block for a base.”

After roping the cumbersome contraption to the roof of their station wagon, the small group headed off towards the heart of New York City, stopping at a hardware store on the way to pick up flares to light their homemade menorah.

“The whole afternoon we were announcing that we’d be lighting our menorah at 5 p.m.,” continues Rabbi Shmuel Lipsker, today the New York-based administrator of Colel Chabad, a charity founded in 1788 by Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi to support Israel’s needy.

“Now, you have to remember, this was before public menorah-lightings; the concept didn’t exist. It was such a huge attraction. We were giving out menorahs, and more and more people were gathering around us. By the time we lit our menorahs with the flares, we had a huge crowd. It was unbelievable—just a knockout.”

The group continued lighting their menorah in Manhattan, and by the next year, a new tool in the fledgling Chanukah campaign was officially born.

But it didn’t come without a few challenges.

Late one night of Chanukah around 1975, the Rebbe was concluding an unscheduled farbrengen (informal gathering) at 770. Outside the synagogue were parked a handful of cars with menorahs attached to their roofs, the vehicles having all just returned from a long evening of distributing small metal menorahs and spreading Chanukah cheer.

As the Rebbe prepared to leave the synagogue to head to his home on nearby President Street, the yeshivah students clambered onto the cars to place flares into the menorahs and light them, hoping the Rebbe would see and be pleased with their work. Seventeen-year-old Bentzion Stock found himself struggling to ignite his last flare as the Rebbe stepped outside.

“One of the flares just wouldn’t light,” recalls Stock, who is now director of Associated Beth Rivka Schools in Brooklyn. “The Rebbe came out and stood there watching me. It was windy; I was getting burnt from the flare, and I was very nervous because I knew the Rebbe was watching. After a few minutes, it still wasn’t lighting, so I climbed down off of the car. Then I see the Rebbe motioning to me that I should get back up.”

Scrambling back on, Stock finally managed to get the stubborn flare to catch fire.

“I looked up,” he says, “and I saw the Rebbe smiling.”

Innovative Outreach

By the 1980s, many of Chabad’s various innovative outreach methods had already been introduced. Public menorah-lightings were sprouting up around the country, including the National Menorah across from the White House, which was lit by President Jimmy Carter in the midst of the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979. And then there were the RVs—known as Mitzvah Tanks—outfitted with Jewish books, tefillin and Shabbat candles, and driven along the streets of Manhattan, which also helped prompt the appearance of car menorahs.

Contrary to what many believe, the Rebbe did not himself institute the particular outreach methods that his followers developed. “Rather than giving detailed orders, the Rebbe often gave top-line assignments, leaving it to the Chassidim to determine the best strategies and tactics,” writes Rabbi Adin (Even-Israel) Steinsaltz in his recent book My Rebbe. “When the commander says only, ‘You must take that hill,’ the soldiers themselves have to find the way to do so.”

A case in point was the car menorah.

“Those early car menorahs were crude wooden things,” remembers Rabbi Mendel Feller, who studied in the Oholei TorahYeshiva in Crown Heights in the mid-1980s. “And we lit the menorah with flares, which looked great but was actually pretty dangerous,” continues Feller who today is rabbi of Upper Midwest Merkos-Lubavitch House in St. Paul, Minn.

Wood was upgraded to plastic PVC pipes until Sholom Ciment, an inquiring 19-year-old classmate of Feller’s at Oholei Torah, saw a yeshivah janitor fixing a broken brass radiator in the winter of 1987. He started asking the man questions, wondering whether he could similarly weld hollow metal tubes in the shape of a menorah, and whether they could run wires through it which they could connect to a car battery via the cigarette lighter.

When the janitor affirmed their supposition, the boys got to work creating their light-bulb-topped metal menorahs.

“If I had to guess, I’d say our class made about 40 or 50 of them,” says Ciment, a Boston native who now serves as co-director of Chabad Lubavitch of Greater Boynton Beach in South Florida. “We started working on the menorahs every night—not during study time, of course. All of a sudden, we all became electricians.”

Although the electric lights on the menorahs weren’t suitable for making a Chanukah blessing (the blessing may only be made when kindling an actual flame), the car menorah’s goal was instead Pirsumei Nissa—publicizing the miracle of Chanukah.

“We called various community members in Crown Heights and sold our menorahs at cost to them,” he says. “That year, we made the very first car-menorah parade, which was an incredible sight.”

New Designs, New Thinking

These days, car-menorah parades can be seen throughout the world. The menorahs themselves show up atop stretch Hummers in Boston; Mini Coopers in Vancouver, British Columbia; Smart Cars in Budapest; and Bentleys in Manchester, England. Car menorahs brighten the dark winter nights as they drive by, reminding pedestrians and drivers alike of the miracle and resilience of the Chanukah story, as well as the power of light.

Development of the car menorah, however, did not end in the 1980s. In the mid-1990s, Nochum Goldschmidt was a yeshivahstudent studying in Sydney, Australia, when he realized that community members were starting to become more reluctant about placing the still-bulky apparatuses on their vehicles.

“We took a survey in the community, and we got three main complaints: They’re too tall and don’t fit in a garage; they’re too bulky for storage; and they were scratching up people’s cars,” explains Goldschmidt.

So he went back to the drawing board to design a new-and-improved car menorah—one that might satisfy all three issues. He met with success, and shortly thereafter, in 1998, started Carmenorah.com. Sixteen years later, he’s still at it, with thousands and thousands of car menorahs sold. Signs adorning them can be customized for different communities; Goldschmidt has printed Chanukah greetings in German, Spanish, French, Russian and Chinese.

“What’s interesting is that over the years, we’ve begun seeing more and more orders being made from outside the Chabad community,” he notes.

Goldschmidt recently added a sign that simply says “Happy Chanukah,” in addition to the standard “Chabad wishes you a Happy Chanukah.”

“There was a time,” acknowledges Ciment, “when a lot of people weren’t comfortable displaying their Judaism in the public square. Times have changed drastically, and both public menorahs and car menorahs have taken hold in all spectrums of the Jewish community.

“There are literally thousands of public Chanukah displays around the world,” he says, “and that is certainly an innovation of the Rebbe’s.”