Tablet Features Article on the Rebbe and Bobby Fischer

Author Jonathan Zalman prepared a story in long-form for the Tablet Magazine in which he decodes a story of the Rebbe with famed World Chess Champion Bobby Fischer.

Zalman was assisted by Rabbi Dovid Zaklikowski, director of Lubavitch Archives, who has done much research into the story for his future book about the Rebbe, and Rabbi Ari Kirschenbaum, director of Chabad activities in Prospect Heights.

Tablet Magazine titled the article Bobby Fischer vs. The Rebbe: The chess genius denied he was a Jew, but the Lubavitcher Rebbe disagreed. Who was right? and it focuses on Fischer’s rejection of his Judaism and anti-semetic statements and the Rebbe reaching out to him about his Judaism.

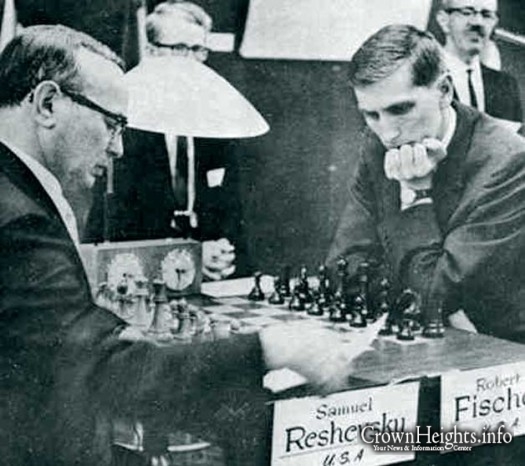

The Rebbe reached out to Fischer through another World Champion Sammy Reshevsky. Here are selections from the article:

Before it was Bobby Fischer, America’s great white chess hope was Samuel Reshevsky, an Orthodox Jew and seven-time U.S. Chess Champion who did not play on Shabbos. A positional player, Reshevsky was born in Ozorkow, Poland, and began playing at the age of 4. He became an International Grandmaster at 39 and defeated seven world champions in his lifetime although his main profession was that of an accountant. In the summer of 1961, Reshevsky, then 50, played a 16-game match versus 18-year old Fischer who hadn’t lost a game in American tournament play in four years. The match was played at the Beverly Hills Hilton and billed the “Match of the Century,” and the winner would take home 65 percent of the $8,000 prize money.

With the match tied 5½ -5½ (1 point for a win, 0 for a loss, and a half point for a tie), the contest hit a snag when the 12th round, slated for a Saturday, was rescheduled for the following day due to Reshevsky’s religious observances. Additionally, Jacqueline Piatigorsky, one of the match’s sponsors, required the match to begin at 11 a.m., citing her own travel needs. Fischer, whose circadian rhythm was that of a bartender, failed to show for the morning commencement. The game was ruled a forfeit. When Fischer was absent from the 13th match too, Reshevsky was declared the overall winner. (Fischer would ultimately sue his opponent and the American Chess Foundation; the case was eventually dropped.) As Frank Brady notes in Endgame, a 2011 biography of Fisher, the result of the match “was the unfortunate casualty of Bobby’s ingrained sleep habits and long shadow of patronage in chess.” A few years later Fischer became a disciple of the Worldwide Church of God; ironically, its tenets forbade him from competitive chess on the Sabbath.

At the 1963-64 U.S. Chess Championships, Fischer tallied an 11-0 record, the only perfect score in its history, defeating his rival Reshevsky along the way. The victory, his fifth in the U.S. championships, would earn him the title of International Master. He would go on to retain his crown two more times for a record eight in front of Reshevky’s seven. In late 1968, Fischer unexpectedly took 18 months away from chess, returning in 1970 to play in the “USSR vs. the Rest of the World” tournament in Belgrade. This time, Reshevsky was his teammate.

“Samuel Reshevsky’s game vs. Vasily Smyslov had been adjourned,” writes Brady. “Back at the Metropol Hotel, Bobby sat down with Reshevsky to analyze the position and consider possible strategies the older grandmaster might play when the game resumed. After ten years of bitterness and competition, this was the first time Fischer had had a friendly interchange with his American rival. (The next day Reshevsky won his game).” Fischer, writing for Brady’s (now-defunct) Chessworld magazine years later, would name Reshevsky as one of the 10 greatest chess players of all time.

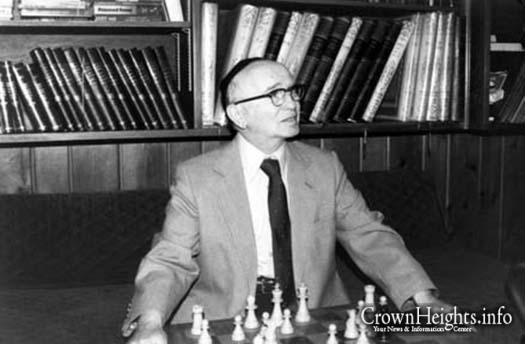

Known affectionately in his youth as “Shmulik der vunderkind,” Reshevsky lived in Crown Heights and developed a relationship with Rabbi Yoseph Yitzchak Schneersohn, the sixth Chabad-Lubavitch Rebbe. He once asked for a blessing from the Rebbe, who agreed on the condition that Reshevsky study Torah daily; Reshevsky obliged. Throughout his life, Reshevsky wrote seven books on chess and worked regularly as a journalist. In 1982, at age 70 and no longer competing at a world-class level, Reshefsky was considering retiring from professional chess and approached Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the seventh and last Rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch movement, and asked for advice. According to Dovid Zaklikowski, the Rebbe told Reshevsky that playing chess was his “way of fulfilling the commandment of sanctifying G-d’s name” and suggested that he not hang it up just yet.

And so, in 1984, aged 72, Reshevsky tied for first place at the Reykjavik Open. After his victory, Reshevsky received a congratulatory letter from the Rebbe, which ended:

P.S. The following lines may appear strange, but I consider it my duty not to miss the opportunity to bring it to your attention. You are surely familiar with the life story of Bobby Fischer, of whom nothing has been heard in quite some time.

Unfortunately, he did not appear to have the proper Jewish education, which is probably the reason for his being so alienated from the Jewish way of life or the Jewish people. However, being a Jew, he should be helped by whomever possible. I am writing to you about this since you are probably better informed about him than many other persons, and perhaps you may find some way in which he could be brought back to the Jewish fold, either through your personal efforts, or in some other way.

Inspired by the Rebbe, Reshevsky took it upon himself to seek out Fischer in Los Angeles during a visit to the area for a tournament.

Fischer by then virtually disappeared from public view—with one exception. One day in 1981, Fischer went out for a walk in Pasadena. Because of his aversion to Western medicine, he now sported a limp and many of his teeth were rotted or had fallen out. He had also grown a paunch. In other words, he was a shell of the custom-suit-wearing chess stud who’d taken the world by storm.

Sometime in early 1984, though, he did receive one visit: Reshevsky. What’s on record of the visit is that the chess prodigy agreed to meet with his elderly former rival for three hours. During that time, they spoke about chess. When Reshevsky spoke of the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s desire to get him involved with Judaism, Fischer became exasperated and requested that his long-time chess foe and friend leave.

Shortly thereafter on June 28, 1984, Fischer typed a letter to the Encyclopaedia Judaica Jerusalem offices at 866 Third Ave. in New York City:

Gentlemen:

Knowing what I do about Judaism (sic), I was naturally distressed to see that you have erroneously featured me as a Jew in ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA. Please do not make this mistake again in any future additions of your voluminous, pseudo-authoritative publication. I am not today, nor have I ever been a Jew, and as a matter of fact, I am uncircumcised.

I suggest rather than fraudulently misrepresenting me to be a Jew, and dishonestly abusing my name and reputation as a kind of advertising gimmick to improve the image of your religion (Judaism), you try to promote your religion on its own merits—if indeed it has any!

In closing, I trust that I am not being unrealistically optimistic, in thanking you in advance for your anticipated cooperation in this matter.

Truly Yours,

Bobby Fischer,

The World Chess Champion

***

According to Dovid Zaklikowski, the director of the Lubavitch Archives, the sixth Rebbe, Yosef Yitchak Schneersohn, asked a disciple to instruct his son-in-law, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, upon his arrival in New York in 1941, to organize a public gathering once a month. At these farbrengens, Schneerson’s son-in-law, who would follow in his father-in-law’s footsteps as the seventh and last Rebbe, would focus his meaningful commentary on a particular subject. Once, in 1949, Samuel Reshevsky attended a gathering led by Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who spoke of chess:

The king is the most valuable piece on the chessboard. Protecting the king and attacking the pieces, which threaten the king’s “dominion” is the objective of the game, and the goal of all the pieces at the king’s disposal.

The same thing is true with all of created reality. The king represents the King of the Universe. When G-d created the world, He had an end-goal in mind—that this G-d-denying reality be made into place where His dominion is known. Just as all of the pieces in the chess game exist in order to fulfill this deepest desire of the King of kings.

While the king represents the transcendent quality of G-d, the queen represents malchut d’Atzilut, G-d’s immanent quality. This quality of G-d generates the rest of the spiritual hierarchy, including all the angels and souls.

The officers—rooks, bishops, and knights—represent the angels. They inhabit the spiritual worlds and channel Divine energy to the worlds below and are imbued with great powers.

And on the lowest rung are the pawns, which represent the souls of Jews as they are embodied in physical bodies in this world.

Every level of this hierarchy has a unique position and method of moving, in accordance with its mission.

On the lowest rung, but on the front lines, are the pawns. Like the pawn that can only go forward one step at a time, we make the world into a place where G-d can feel at home by moving slowly, step-by-step. We do our work with simple actions that are often not very glamorous. Although we can achieve a lot, we must work within the limits of the natural universe.

However, when a pawn finally completes its step-by-step progression and reaches the other side, it can be swapped and promoted to a higher level. It is even possible for a pawn to attain the level of queen.

This is also true spiritually: It is possible for a simple human soul to be united with its source malchut d’Atzilut, to be charged with the level of G-dliness that is higher than all the angels and souls. We are the only ones in all of the realms of created reality that are capable of this kind of drastic transformation. …

And what does it mean to win a game of chess? What is the future that even G-d Himself will drop everything to save? It means to win the war of all wars: when the world will be a place of good and harmony, peace and tranquility; when no part of G-d will be in exile; and when the essence of G-d will no longer be “removed” from creation.”

Rabbi Ari Kirschenbaum, director of Chabad activities in Prospect Heights and Fort Greene, says that when the Rebbe sent Reshevsky to see Fischer, he was testing his theory; if Fischer could recognize his Jewish soul, his culture, his people, and his identity, he could overcome his inner hatred and embody malchut d’Atzilut—become the queen. In a recent interview in Kirschenbaum’s home, he read me an excerpt from a talk the Rebbe gave, influenced by his father-in-law, the sixth Rebbe, about what it means to be a Lubavitcher Hasid, which he says, can apply to Jews and non-Jews alike: “A Hasid is like a street lamplighter. In olden days there was a person in each town who would light the streetlamps with the light he carried on the end of a long pole. There must be someone to light even those lamps so that they may meet their purpose and light the lamps of others.”

While the Rebbe was not interested in using Fischer as evidence of Jewish genius, the chess master’s apprehension that he was being used was not entirely wrong. Saving Bobby Fischer’s troubled soul—his Jewish soul—would be proof of the Rebbe’s theory of the spiritual potential inherent in every Jew. But was the Rebbe’s theory right?

The first place to look for evidence of Bobby Fischer the lamplighter is within the game of chess itself—in America. When Fischer won the 1972 chess championship, he had to overcome a formidable Russian chess regime, one that was and continues to be subsidized by their government. The United States did not have, nor does it have today, federal chess scholarships. Brooklyn Castle, a 2012 documentary, tells the riveting story of a group of New York City middle-school students at “below the poverty line” I.S. 318 in Brooklyn, who use chess as a springboard for life—teamwork, individual focus, building character through failure, appreciating success. The school boasts one of the best chess teams in the United States, winning more national championships than any other middle school in the country—a testament to the inroads Fischer blazed himself, becoming the only FIDE world chess champion the United States has ever produced, at a critical moment in the country’s Cold War confrontation with the Soviet Union.

While many viewed Fischer as a greedy diva, he saw a dearth of money within a game that took everything within an individual to reach the top, so he fought tooth and nail for every penny. Today, as a result, tens of thousands of dollars can be won in international play on a regular basis. Susan Polgar’s program, SPICE, currently grants scholarships to chess-playing students from eight countries. And Norwegian Magnus Carlsen [24], the world’s current No. 1 chess player, has made numerous national television appearances, including on 60 Minutes and The Colbert Report (he beat the host at rock-paper-scissors).

yg

There are several mistakes

1) Reshevsky was never world chess champion.

2) Fischer was never a member of

the church. The church used to advertise in chess magazines. The church said that the messiah would come in 1975. In 1976 Fischer lost interest .

3) Great white hope?. Out of over 1,000 Chess Grandmasters, only one is black..

4) Fischer’s IM title did not come in 1964. He became a Grandmaster ,a higher title, in 1958 at the age of 15.

5) Reshevsky asked the the Fred Rebbe for a blessing to avoid the draft. The Fred. Rebbe answered that if he takes upon himself the yoke of torah by learning daily he will be freed from yoke of army

That is enough for now. Lastly, Reshevsky never played the Rebbe a game of chess.

SM

yg: while you’re surely a wonderful fellow, your erroneous comment begs the question: why do you seem so eager to detract from this piece…

1: It is expected that you would admit that Grandmaster Reshevsky was a top four World Champion, and won the U.S. Championship six times, instead of detracting.

2: Nowhere afaik did this piece say he was a member of the co-G, it said he was a “disciple”, which you apparently accept yourself given your stating that he “lost interest” in 1976 (note: this timing afaik would concur with the piece).

3: ‘Clearly’ the employment of the known term “great white hope” was used figuratively to refer to a candidate America or Jews hoped would bring them a World Championship title. Quite appropriate considering the subject matter being a championship title. Note: He is white nonetheless.

4: The piece afaik correctly points out that Fischer won the IM title in 1963/4 this not detracting from any previous titles, higher or not, that he may have won, and hence is not a mistake, unless you’re suggesting he didn’t win the IM title that year.

5: The piece cites the story with the Previous Rebbe without error, though it does apparently employ discretion in not mentioning what personal blessing he asked for.

Lastly, nowhere afaik does this piece say that the Rebbe and Reshevsky played chess across from one another. Either way, your saying they never did begs the question, how would you know?! Were you present for every encounter between the Rebbe and Reshevsky?! It wouldn’t come as a surprise if they did.

Kudos to both Grandmasters. It’s a shame that after the piece quotes Fischer denying any Jewish roots altogether, that it fails to elucidate afaik a discovery or admission to the contrary, or elucidate his having come closer to Judaism.