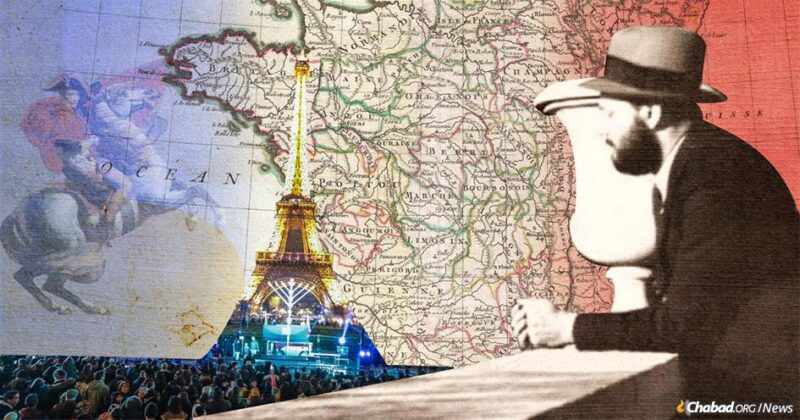

The Rebbe’s French Revolution

by Mordechai Lightstone – chabad.org

Thousands of eyes were trained on the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—as he stood at the center of the cavernous synagogue at 770 Eastern Parkway, Chabad-Lubavitch World Headquarters. It was time to begin the hakafot, the Simchat Torah tradition of dancing with the Torah scrolls. Yet despite the crowd beginning various lively Chassidic tunes, none seemed to catch the Rebbe’s attention. Suddenly, the Rebbe walked to the end of the platform he was standing on in the center of the synagogue and turned towards those gathered. A hush fell over the room, as people craned in to hear the Rebbe sing an unfamiliar tune.

Suddenly, someone, one of several dozen students from France visiting for the holiday, shouted, “It’s La Marseillaise! The Rebbe is singing the French national anthem La Marseillaise!”

This is the story of how the French national anthem was transformed into a bold, Chassidic March, corresponding with a renaissance of French-Jewish life.

The evening of Simchat Torah 5734, Oct. 19, 1973, when the Rebbe taught “La Marseillaise,” was marked with an unmatched intensity. That year, a Hakhel year of Jewish gathering, saw an unprecedented surge of guests come to the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., to spend the month of Tishrei holidays with the Rebbe. Less than two weeks earlier as millions prayed in synagogues on Yom Kippur, the Egyptian and Syrian armies surprised Israel by attacking the country on two fronts. Israeli forces were caught unprepared, and casualties in the Holy Land rapidly grew.

While encouraging Chabad Chassidim in Israel to take an active part in the war effort, the Rebbe stressed the critical need for those on and off the front to remain not only positive, but double down in “barrier-breaking joy.” Quoting a popular saying of the fourth Rebbe—Rabbi Shmuel Schneersohn of Lubavitch—the Rebbe reflected, “when one comes upon an obstacle, the popular response is to try and avoid it, and only if left without option, leap over it. Rather I say, lechatchila ariber, leap and transcend it in the first place.” Joy then, would be the order of the day.

With Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah, the apex of the rejoicing on the Jewish calendar, 770 seemed poised for something truly momentous. Only a few days earlier, the Israeli army had turned the tide of the war, crossing the Suez Canal, and was continuing to advance. Thousands of miles away, a veritable sea of humanity pulsed with the rhythms of the Chassidic melodies and powerful joy of the evening.

An Unforgettable Experience

Simchat Torah with the Rebbe was an experience even eyewitnesses struggled to express in words. Describing a Simchat Torah a few years later, Zalmon Jaffe, a businessman from the United Kingdom, wrote: “I saw the Rebbe dancing with his brother-in-law. A small Sefer Torah was held on each right shoulder and each left hand rested on the left shoulder of the other. They danced round and round even faster—the Rebbe forcing the pace all the time. Looking down, all I could see was what looked like a thick black carpet, moving up and down with quick rhythmical movements. From every pillar in the hall, which supported the roof and ceiling, hung four or five boys. They resembled palm trees with hanging bunches of coconuts or clusters of dates.”

As was customary, for each hakafah, prominent rabbis, visiting dignitaries and Jews of all ages and backgrounds would be called to take part in the dancing. That year, various elder Chassidim joined the Rebbe for the fourth hakafah. Each was given one of the smaller, lighter Torah scrolls to hold while dancing. The Rebbe honored the young Rabbi Shmuel “Moulé” Azimov with carrying the “Sefer Torah to Greet Moshiach,” a large Torah scroll begun by the Sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn in 1942. Though only 28 himself, Moulé and his wife, Bassie, had been sent by the Rebbe in 1968 to lead Chabad’s activities across Paris and its environs.

The Rebbe and his wife, Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka, had lived in France for most of the 1930s, and the French Jewish community remained of particular interest to them. As the Rebbetzin told Bassie Azimov before the young emissary moved to Paris, “We plowed and sowed, so that you could harvest.” That year, 1973, the Azimovs had brought a particularly large group—some 60 young men and women made the journey to spend the holiday with the Rebbe. To honor the group, the Rebbe requested that all the guests from France join their rabbi in the dancing.

Among those who made the trip was Chaim Nissenbaum. Today the rabbi of Beth Chaya Mushka synagogue in Paris and a spokesman for Chabad-Lubavitch in France, Nissenbaum had grown up in what he calls a “traditional,” if non-Orthodox, Jewish household. “It was my second trip to spend the holidays with the Rebbe,” he recalls. “Everything was still very new to me and it was truly an incredible experience.”

When at last the group had gathered, the hakafah began.

“One of the elder Chassidim began to sing a niggun,” Nissenbaum recalls, “but the Rebbe didn’t join in. It became clear the Rebbe wanted to sing something else.” People began to hush those singing. Suddenly, the Rebbe walked to the end of the platform he was standing on, turned towards the crowd and began to sing.

Chassidim, unable to make out even the words, craned in to hear the unfamiliar song.

That’s when one of the French guests shouted that the Rebbe was singing the tune of “La Marseillaise.”

Nissenbaum listened intently, and realized the guest was right. The Hebrew words the Rebbe had substituted of the anthem’s were easy enough to pick up, HaAderet VeHaEmunah—an alphabetical acrostic poem popularly recited during Simchat Torah dancing—but the tune was unfamiliar to most in the room. “We began to sing with great excitement, but none of the Americans could catch on.” Nissenbaum said. “It felt like this incredibly special moment for us French Jews.”

The next day, at the farbrengen held at the closing of Simchat Torah, the Rebbe called for the French guests to join him once more. Soon, French Jews, who were scattered throughout the thousands crammed in the synagogue, started climbing over the heads and tables to make their way to the center dais where the Rebbe sat. After handing a bottle to Azimov to honor each guest with either a l’chaim or a slice of challah, the Rebbe turned to them with a large smile. Then, in French, he declared:

“Je vous donne lechaim pour faire la révolution en France contre le Yetser Harah ‘as soon as possible’, besimchah, avec joie et inspiration. Et le bon Dieu vous bénira pour être mekabel pnei Mashiach tsidkenu bekarov.”

“I give you all l’chaim to lead the revolution in France against the Yetzer Harah [in English] ‘as soon as possible’, besimchah, with joy and inspiration. And the good L-rd will bless you to [switching to Hebrew] ‘greet Moshiach soon.”

A Chassidic Musical Tradition

The practice of subverting a song from a non-Jewish source and entering it into the canon of Jewish holy music has a long and storied history among Chassidim. Russian, Belarussian and Ukrainian peasants were a source for beloved songs, which were adapted by neighboring Jews and infused with new Chassidic meaning. This concept connects closely with the Baal Shem Tov’s teaching to find the Hand of G‑d—and a lesson for our personal lives and Divine service—in everything we see or hear. Surely, Chassidim believed that the words and songs of their neighbors could be mined for meaning and elevated through application.

More directly, in 1812, during Napoleon’s ill-fated invasion of Czarist Russia, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi—the founder of the Chabad movement—co-opted the music of the French troops. When the 450,000 men of La Grande Armée, then the largest military force assembled in European history, crossed into Russia, Rabbi Shneur Zalman instructed his followers to spy on the French troops to gather information for Russia.

The decision to align the Jewish community with the Czar was far from a simple one. Indeed, the Chassidic Masters Rabbi Yisrael Hopstein (the Maggid of Kozhnitz), and Rabbi Mendel of Riminov, among others, supported a French victory.

Rabbi Shneur Zalman was well aware of the cruelty of the Czar and suffering of his Jewish brethren in the Russian Empire; he himself had been held in Czarist prison twice at that point, in 1798 and 1801. Yet in Napoleon, Rabbi Shneur Zalman saw the apex of the French Revolution and its Reign of Terror. As Napoleon once remarked: “Were I obliged to have a religion, I would worship the sun—the source of all life—the real god of the earth.” A man ruled only by his ego could not be the herald of liberty and emancipation, but rather the complete antithesis of anything G‑dly. While making clear his staunch opposition to Napoleon, Rabbi Shneur Zalman also spent months setting up emergency housing and providing material relief for the Jews living in the path of the emperor’s advancing armies. Ultimately, while Napoleon’s hubris would kill upwards of 280,000 of his men and leave him in defeat, the Jewish soul would remain resilient.

Speaking to the Chassidim spying on Napoleon, Rabbi Shneur Zalman inquired as to the tune the French were marching with. Upon hearing it, he proclaimed: “This is a song of victory!”

In an act of spiritual defiance against Bonaparte, Rabbi Shneur Zalman “claimed” the tune.

The song, known today as Napoleon’s March, remains an ode to spiritual fortitude and victory. It is popularly sung at the end of Yom Kippur to signify the Jewish people’s certainty that they’ve been victorious in the heavenly court drama, and that G‑d has sealed them in the Book of Life.

The Ultimate Victory March

Speaking on that Simchat Torah, the Rebbe noted his own decision to transform “La Marseillaise” followed in this tradition.

“My intent was not that someone sitting in Brooklyn should learn a new song,” the Rebbe explained, “but rather those Jews from France should march with it victoriously to greet Moshiach.”

“We were just this group of young people,” Nissenbaum remembers. Many of those in attendance had only begun to explore Jewish observance, “but we brought this song back to France and with it, this incredible enthusiasm, an awareness that we could change the country.”

The work seemed daunting. The cradle of Europe’s Ashkenazi community, France’s Jews faced assimilation in the 19th century and had been decimated during the Holocaust. A pernicious legacy of antisemitism, epitomized by the Dreyfus Affair and cultural tradition of Laïcité, French Secularism, meant that even as Jews returned to France, Jewish life was a muted affair.

“In the France of my youth, many Jews were ashamed to be publicly identified as Jews,” Nissenbaum recalls. “Religion was kept private, definitely not practiced openly on the street.”

Despite this legacy of antisemitism and assimilation, France’s Jewish community was going through rapid demographic transformation. Postwar France became a haven for refugees, tripling in size over the next 25 years. The country’s liberal immigration policies were particularly attractive to the French-speaking Jewish communities of North Africa. By 1968, the same year the Azimovs moved to Paris, Sephardic Jews had become the majority in France.

With time the Azimovs built an educational empire, bringing dozens of other emissaries, many of them the students who attended that very Simchat Torah. Today, there are more than 450 emissary couples running 115 Chabad-Lubavitch centers in 164 cities and communities in France.

The song, now known by its Hebrew lyrics “HaAderet VeHaEmunah,” became emblematic of this transformation. On Nov. 30, 1991, the Rebbe noted how thoroughly France was transformed. The bastion of freedom from responsability to G‑d, had been “utterly transformed into a bastion of G‑dliness in this world.”

The transformation of the French national anthem was indicative of this epoch in Jewish history. “This song has been completely transformed into something holy,” the Rebbe said. “To the extent that some people sing it and don’t even realize this Chassidic tune began its life ‘elsewhere.’ ”

“The Rebbe lived in France for many years,” Nissenbaum reflects. “He had a special attachment to French Jewry. And so he gave us this as a present. He took the national anthem of the country and transformed it into something holy, something that reflects the transformation of Jewish life.”