‘Roving Rabbis’ Report: Jewish Life in Remote Saskatchewan

by Mendel Super – chabad.org

It was a chilly night as we disembarked the plane at John G. Diefenbaker Airport, the winds sweeping through the endless plains. This was my third time in Saskatchewan, having previously been assigned by Chabad-Lubavitch headquarters to help out at local Chabad centers in Regina and Saskatoon for the holiday of Shavuot. But this time was different. I wouldn’t be spending just a few days in the major cities with an established Jewish community. I was here for a vastly different purpose: to meet Jews scattered throughout the province, in cities, towns and villages with no existing Jewish infrastructure, helping them keep their Jewish flame burning.

My colleague, Rabbi Eliyahu Citron and I had been selected to be a part of Chabad’s “Roving Rabbis” program, which sees young rabbis visit remote Jewish communities in more than dozens of countries every summer. The essential purpose is to help foster Judaism by reaching out to every Jewish man, woman and child wherever they may live, from the biggest cities to the most remote parts of the globe, and to enhance our own training as rabbis. The program was initiated in 1943, with its beginnings in New York State. By the next few years, it had spread across the United States and Canada, and then across the globe by the 1950s. In 1990, Chabad began to dispatch young rabbinical students to visit Saskatchewan every summer, and Rabbi Raphael Kats invited us to bring this program to rural Saskatchewan this year.

I had previously served in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Cambodia, St. Lucia, throughout Australia and in the United States. But the Canadian Prairies intrigued me. With their vastness and fascinating Jewish history, it promised to be an altogether new experience.

I invite you to join Rabbi Eliyahu and me as we relive our trip through rural Saskatchewan—from Estevan to Prince Albert—meeting the Jews who live there and listening to their stories.

It was an unseasonably hot day as we set out toward Melfort, a short hour and 45 minutes out of Saskatoon. Melfort once had a shul, used by Jews throughout the region and, after the closing of the Edenbridge synagogue, by the remaining farmers of the colony. But today, almost three decades after its closure, we wondered whether any Jews were left. We had an address of one older gentleman but had no idea whether or not he still lived there. We knocked on the door. No answer. A little dejected, we began to walk back to our car when we saw someone approach the building. Taking a chance, we asked him if he perhaps knew Harry, the man whom we were seeking. “I am Harry,” he replied with a surprised look on his face. Harry, it turned out, had been born nearby to a Jewish farming family with strong ties to Edenbridge. After the rest of the Jewish population had moved to the larger cities and his father had passed on, Harry had little opportunity to meet other Jews and to practice his faith. He gladly took the opportunity to lay tefillin. Memories of his bar mitzvah all those years ago in a shul that is no more began to come back, bringing a smile to his face and tears to his eyes.

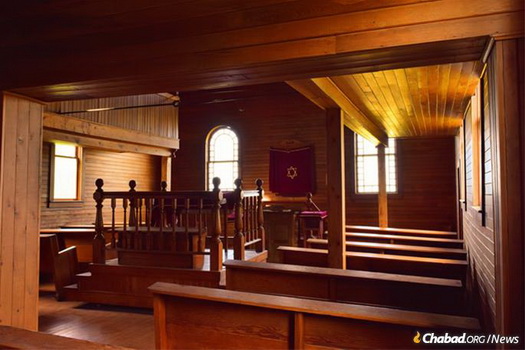

Almost 30 miles northeast of Melfort lies Edenbridge, with its shul and cemetery the only remnant of a once-proud Jewish agricultural settlement. When Edenbridge was founded, it would have been an arduous journey from Melfort and an impossible trek for poorer settlers who didn’t own oxen or horses. But now, more than a century later, we found the historic site with little difficulty. Appearing out of nowhere on the side of a dirt road was the shul, today the oldest standing synagogue in all of Saskatchewan. Inside, wood paneling covered the entirety of the sanctuary, with the women’s gallery overlooking the bimah in the center. Many a farmer would have come to this small shul to pour his heart out to his Creator, saying the words of the Amida prayer, asking G‑d to bless the year’s produce and send rain upon the land.

A Once-Proud Agricultural Settlement

Edenbridge was established at the turn of the century by a group of Lithuanian Jews who had immigrated to South Africa seeking a better life. After seeing an advertisement for land in Canada for extraordinarily low prices, they arrived in the vast untamed wilderness, plots of which they were now the proud owners. They were soon joined by contingents from London and the United States, and worked hard to tame the prairie.

When the time came to establish a post office, the town needed a name. The settlers suggested “Jew Town” and “Israel Villa,” which were rejected by the officials as unsuitable. They then decided on Edenbridge. To the officials, it sounded like “Paradise Bridge,” but to the Jews, it would be “Yidden Bridge” or “Jew Bridge.”

Life wasn’t easy on the undeveloped, vast expanse of coniferous trees known in northern Canada as “the bush”, and many early pioneers perished from disease and starvation. Behind the shul in a clearing lie the founders and pioneers of the colony, many of whom gave their very lives for their dream of self-determination. Walking between the graves, we noticed how many of those buried there passed away at a relatively young age—young mothers and fathers leaving behind their young brood. One tombstone in particular stood out, that of Philip “Shrage Faivel” Gordon, who passed away at age 52. Inscribed on his tombstone in Hebrew is a verse paraphrasing the words of King Solomon in Ecclesiastes 2:10, which perhaps best encapsulates the sentiment of those pioneers:

“‘And this was my reward for all my endeavors’ – Edenbridge.”

From Edenbridge, we continued on to Prince Albert, which was once home to a Jewish community, and had its own synagogue and cemetery. Today, the shul has become a church, and to the best of our knowledge, almost no Jews remain in Prince Albert.

Visiting a Prison and a Cemetery

After following up with a few leads in town, we went to the Saskatchewan Penitentiary, unfortunately home to a handful of Jewish inmates. We spoke about how in Judaism’s view, prison time ought not to be solely about keeping people off the streets, but focused on reflection and rehabilitation, so that once released they can return to society as upstanding citizens. Indeed, several of those whom we visited told us they had become more involved in Judaism during their sentence, and had a positive influence on their fellow inmates as well.

We then traveled west to North Battleford. Like many towns, it too had its own synagogue, which discontinued operations in the ’90s. The shul is now a private residence, occasionally being rented out as an event hall and known as “The ‘Gog,” in tribute to the synagogue that once occupied its space.

Online we couldn’t find any information on the existence of a Jewish cemetery, so we did what we often do when arriving in a town: make a stop at City Hall. The clerk was very helpful and showed us where the Jewish section was on the cemetery map. He informed us that just several months ago, a 104-year-old woman was buried in that section. We inquired as to whether there are any local Jews in town who handle Jewish burials. The helpful clerk contacted the cemetery manager, who told us that they do it themselves, as there is no longer any Jewish burial society. “But,” he said, “there’s one Jewish family left in town. Friedman is the name.”

Now we had to track down this family, but where to start? We didn’t even have a first name. Off to the town library we went to check in the White Pages. We located two Friedmans, so we figured we’d try them both. The first wasn’t home, so we tried the second address. As we pulled up to the home, with a menorah attached to the roof of our car, a man stood outside waving as if he was already expecting us. “I’d love to meet with you,” he said, “but I’m going to fetch my dad now, and then we’re going to Saskatoon. Follow me, and you’ll meet my dad and my sister.”

We followed him to his sister’s house, where to our amazement, three generations of Friedmans were sitting on the front porch. We discovered that the patriarch of the family, Bob, had lived in North Battleford all his life and stayed on even after most of the other Jewish families left. His daughter, Rachel, shared with us a newspaper clipping of her bat mitzvah, the first, and so far the only one that North Battleford had seen. Rachel has a 16-year-old son who had never had a bar mitzvah, so we were delighted to celebrate an impromptu one right there and then. As we laid tefillin with the bar mitzvah boy for his very first time, his sisters, parents, uncle and grandfather looked on proudly. Then, his uncle and grandfather put the tefillin on, too—three generations binding themselves to our beautiful, timeless tradition and to each other. Everyone recited the words of the Shema prayer together, men, women, and children. We encouraged Rachel and her daughters to do the mitzvah of lighting Shabbat candles and gave them several candles to get started with. It was one of the highlights of our experience as “Roving Rabbis” and a meaningful moment for us all.

We visited the Jewish section of the cemetery, which was consecrated in 1980 and contains seven graves.

Our journey southward took us to the site of the Melville Hebrew Synagogue, the second-oldest standing synagogue in the province, built in 1921 and closed in 1970.

The shul in recent years was bought by a local, who resolved to refurbish it and restore it to its former glory.

The outside of the shul indeed looks beautiful, but the inside was converted into a home, leaving just the front section of the synagogue as it originally was.

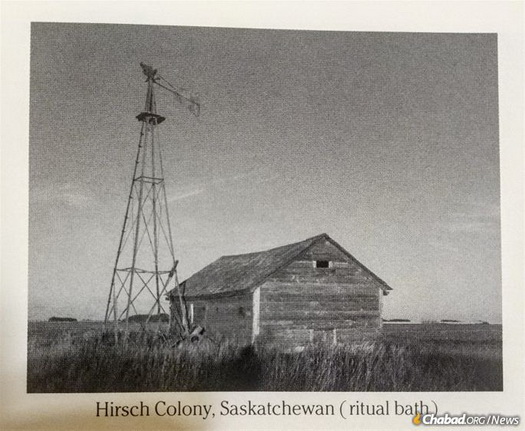

Another fascinating site is the Hirsch Jewish community cemetery outside of Estevan, a settlers’ colony founded by European Jews in the 19th century, funded by the Jewish philanthropist, Baron de Hirsch of Germany. There are dozens of graves with unusually flowery Hebrew inscriptions and many that remain unmarked. The cemetery is the only remnant of the colony, the shul and mikvah no longer standing. The cemetery was established in 1892, making it the oldest Jewish cemetery in Saskatchewan.

A Once-Majestic Shul in Moose Jaw

The next week we visited the south of the province—from Moose Jaw to Estevan. Moose Jaw is home to a majestic shul, perhaps the most outstanding in the province. Built in 1926 and operating until the 60s, the Moose Jaw synagogue once served a large Jewish community. Today, it lies abandoned, previously having been used as a dance studio.

We heard there was a Jewish family in Weyburn, an hour and 20 minutes out of Regina with a population of 10,000. We parked outside City Hall to see if perhaps they knew of any other Jews living there. As we stepped out of our car, another car pulled up alongside us. Rolling the window down, the driver called out Mah shlomcha? (“How are you?” in Hebrew). Excited, I went over and asked him if he was Jewish, and sure enough, he was! He invited us to follow him to his house, where we spent a while with him and his son discussing all things Jewish. We later discovered that this was, in fact, the family we had heard about before, but the address we had was wrong. Had he not spotted us, we would not have found him.

They told us about another Jew living in Hitchcock, a tiny hamlet outside of Estevan. We called him, but he informed us that though he lived in Israel for many years, he wasn’t actually Jewish. However, he shared with us that the owner of a certain establishment in Estevan is Jewish.

According to information we found online, the last Jew in Estevan had moved out several years before. So who was this mysterious Jew? We parked outside the store that our friend from Hitchcock mentioned. A young fellow greeted us at the counter.

“Hey, we’re visiting rabbis looking for local Jewish people. Someone mentioned that the owner might be Jewish?”

“That’s my grandad, Harvey Feldman.”

Harvey is 85, he told us, and only comes in during the morning hours. It was early evening and he would be sleeping now, we learned. We resolved to come back in two days’ time.

Two days later, when we arrived back in Estevan, we met Harvey’s son in the store. He told us that his father was at home. Harvey’s son was rushing out to an appointment, so he jotted down Harvey’s phone number for us. We got through to him, and he was happy to meet us right then at his home.

Harvey was, to the best of his knowledge, the last Jew in Estevan. The Estevan synagogue was long closed, first becoming the home of the town library and now a dance school.

Harvey’s parents were from Poland and had both come to the American shores separately, though they had already known each other back in the old country. They later moved to Canada; Harvey was born in Calgary. After marrying, Harvey settled in Estevan for his job. He told us how one-by-one, all of Estevan’s Jews moved away or passed on, leaving him alone, the last Jew in town. Harvey had never laid tefillin before but recalled seeing his uncle don them regularly. He gladly allowed us to assist him in performing the mitzvah. We asked him if he would like a mezuzah for his front door, and he was happy to put it up. Now, Estevan has a home with a mezuzah on its doorway, hanging proudly for all to see.