Pianist Expresses Poignancy of Chassidic Melodies

Shoshana Michel, 59, started playing piano when she was just a child. A door-to-door salesman for a local music studio came by and asked if anyone in the house wanted to take music lessons. She started on the accordion at the age of 7, and then moved on to piano shortly after.

In high school, she accompanied the choir. Then she fell in love with ragtime music and added the four-string plectrum banjo to her repertoire.

When she was 17 and her brother was 14, the two siblings got a gig at Shakey’s Pizza Parlor (which is still around) in Los Angeles. Afterwards, she landed a job at the well-known Knott’s Berry Farm in Buena Park, Calif., which had opened a “Roaring 20s” area, where she played piano for people walking by.

Michel went to college, got married, got divorced, played for different musicals and performed piano at a food court in Redondo Beach, Calif. She got remarried, moved to the Chassidic community in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., and stopped playing music in the early 1990s. About nine years ago, she moved into a house that could accommodate her piano and started playing ragtime again, and then four to five years ago, she began performing nigunim, traditional Jewish melodies intended to stir and express the soul.

This type of music-playing was prompted at the request of a friend in Crown Heights who asked her to play for Rosh Chodesh, the beginning of each new month on the Hebrew calendar. Though she couldn’t read Hebrew, Michel was familiar with the religious melodies from synagogue services.

“I looked through until I found melodies I liked that sounded pretty to me,” she recounts. Following the performance, “I was really taken aback by the response I got. I didn’t realize the impact nigunim would have on people.”

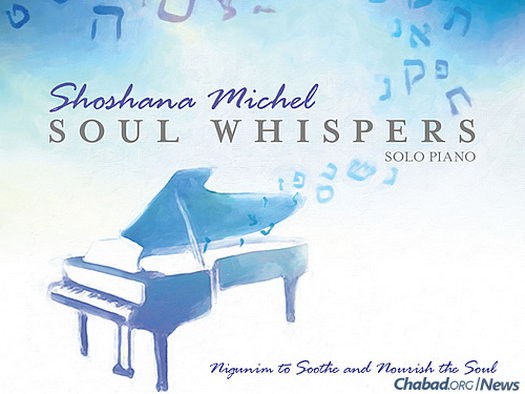

She started putting her song renditions on YouTube, and now she’s marketing her first CD, “Soul Whispers,” which was released this spring. Recorded on a grand piano at New York University over the past two years, she notes that working on the CD opened her up as an artist and a musician. “I’ve been able to compose,” she says, “and I’m able to compose in the New Age genre.”

Joyfulness Through the Music

Michel became involved with the Chabad-Lubavitch movement about 25 years ago. She wanted to become Torah-observant, and so her sister’s mother-in-law took her under her wing.

Today, she’s one of a handful of observant women in her community who play music, she says. She plays for audiences of just women, or men and women separated by a partition, a mechitza, with an eye towards being open to what makes others comfortable, she explains. “It’s great to be able to express what’s in your heart, what’s in your soul. Your music is a part of you.”

A fan of klezmer, she picked Chassidic music when she was exposed to it for the Rosh Chodesh event and has focused on it because it speaks to her. “It’s soulful. The people who wrote it had something in mind; it wasn’t just, ‘I’m going to make a pretty melody,’ ” she stresses. “They had something behind that when they wrote it—the yearning, the joyfulness, comes through the music.”

Michel has played a few concerts in Crown Heights, and is transcribing her arrangements and making them available for people who want to play them.

Meanwhile, her recorded songs are available via online music services, such as Spotify, and will be on Pandora soon, meaning that these nigunim are now being played around the world.

It’s important for the soulful melodies of the nigunim to reach people, she stresses. “It’s very healing. Whatever a person needs from the music, they’re going to get from the music—whatever they need for their soul.”

Michel’s parents have been her biggest musical inspirations, she notes, having exposed her to a wide variety of different music genres. “My father loves classical music and opera, and had encouraged and taught me to be open to all styles of music. My mother loved music from her generation, and I picked up her love for music from the swing era.”

Michel says she feels her Jewish practice and involvement with Chabad opened up a part of her that makes her music more evolved than if she wasn’t observant. “I think I could play all the pieces, but they wouldn’t sound the same,” she says. Now, “I have a connection.”

She even acknowledges sometimes getting goosebumps while playing: “There’s a part of me that is committed to the spiritual aspect of it. The people who composed the melodies … there is a meaning, a whole history, behind most of these pieces.”

heaven

her talent is amazing and her music fuses heaven and earth!!

Shoshana

Thank you for the music!