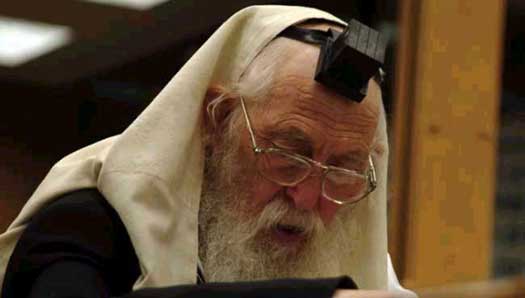

Rabbi Moshe Greenberg, An Educator Who Survived the Gulag

Rabbi Moshe Greenberg, survivor of the Soviet Gulag, as well as an activist for Jewish education under Communist rule and when he arrived to live in Israel, passed away on June 18 at age 84. He was the director of Chabad-Lubavitch of Bnei Brak, Israel.

He was born into a Chassidic family in Kishinev, Moldova, where his father secretly taught him Jewish studies until he was 14. At that age, his parents sent him to the clandestine Chabad-Lubavitch Yeshivah in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. “There was nowhere else to learn besides there,” he told Sichat Hashuvah, a publication of Tzeirei Chabad in Israel.

It was there that he first heard of the plan of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory—to establish a network of rabbis and activists to keep Judaism alive under the oppressive Communist regime.

Those who knew him at the yeshivah told of how he would diligently study Torah and scholarly Jewish texts no matter the hardships entailed in doing so.

At the end of World War II, Greenberg and several friends tried to escape the Soviet Union to Poland; they were caught, and he was sent to Siberia for seven years. There, he was said to have never eaten a morsel of food that was not permitted by kosher dietary laws, no matter how great his hunger, nor did he work on Shabbat.

“I figured that the only kosher food,” he would later recall, “was the 15 grams of bread, the little sugar and a small piece of pickled herring,” which was a minuscule portion of food for the backbreaking work he was required to do in the camp.

Since he refused to work on Saturdays, each week he went into solitary confinement for the day. Local Jews who heard about this felt sorry for Greenberg and would bribe local officials, asking that he be deemed too ill to work and sent to the hospital on Saturdays instead. This apparently went on for years.

“Because everyone was working around me on the Sabbath,” he said in an interview with Sichat Hashuvah, “I had to constantly murmur to myself, ‘Sabbath, Sabbath,’ so as not to come to work on the Sabbath.”

In 1951, before the High Holidays, he asked an engineer who looked Jewish if he could somehow get a machzor—a High Holiday prayer book—into the camp. The man responded that he knew of only one copy; it belonged to someone intending on using it for the holidays. Greenberg asked to borrow it, so he could copy down the prayers.

“To copy it,” wrote his son Rabbi Zushe Greenberg in a memoir My Father’s Machzor , “my father built a large wooden box and crawled into it for a few hours every day. There, hidden from view, he copied the book, line for line into a notebook. After a month, he had copied the entire machzor.”

With his handwritten prayer book, Greenberg served as cantor in the camp and recited each prayer, repeated by other Jews in low solemn voices. After nearly seven years in jail, Greenberg was released, along with political prisoners, upon the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953. His son said the only item his father took with him was the machzor.

Shortly thereafter, Greenberg married Devorah Chazan. He continued his activities on behalf of Jewish education, including making sure his own children received a solid Jewish education.

“The self sacrifice of the Rebbe Rayatz,” he told Sichat Hashuvuah when asked about his devotion to Judaism and assisting other Jews, “caused me to feel that all that I do is minor compared to his activities on behalf of Judaism, while placing his life in danger.”

In 1967, the family was permitted to immigrate to Israel; they moved to Bnei Brak. “That first Sabbath,” Greenberg recalled, “I was called to receive an honor in front of the Torah at the Vishnitz synagogue, and I broke down in tears as I looked around the room in disbelief as Jews practiced Judaism openly.”

Shortly after his arrival, he opened a Chabad school in the city. He also regularly traveled to nearby Petach Tikva to stand on a corner, helping Jews put on tefillin—black leather boxes containing parchment scrolls, worn on the arm and head for weekday prayers.

He also spread Chabad teachings to the religious, hoping to inspire in them with the depths of Chassidic teachings.

His legacy continues as part of the work of his 17 children, many of them Jewish leaders across the globe. “I raised them based on the teaching of the Lubavitcher Rebbe,” he said referring to Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, “and the outcome, thank G-d,” can be seen for itself.

He is survived by Rabbi Naftali Greenberg of Lod, Israel; Rochel Levertov, co-director of Chabad Lubavitch of Austin, Texas; Rabbi Yisroel Greenberg, co-director of Chabad Lubavitch of El Paso, Texas; Rabbi Yosef Greenberg, co-director of Lubavitch Jewish Center of Alaska; Rabbi Zushe Greenberg, co-director of Chabad Jewish Center of Solon, Ohio; Batya Shemtov of Brooklyn, N.Y.; Rabbi Schneor Greenberg, co-director of Chabad of Commerce, Mich.; Rabbi Shmuelik Greenberg, co-director of Chabad Jewish Center of Clark County, Vancouver, Wash.; Rabbi Baruch Greenberg, co-director of Chabad of Oceanside, Vista, Calif.; Rabbi Shalom Greenberg, co-director of Shanghai Jewish Center; Rabbi Avraham Greenberg, co-director of Chabad of Pudong, Pu Dong, Shanghai; Chaya Wolff of Chabad of Odessa, Ukraine; Rivka Azimov of Beth Loubavitch of Neuilly, Neuilly Sur Seine, France; Shterni Wolff, co-director of the Chabad Jewish Center, Hannover, Germany; Esther Shaikevitz of Kfar Chabad, Israel; Rabbi Chaim Yehudah Greenberg of Beitar Illit, Israel; and Chava Kastel of Rechovot, Israel.

do

do