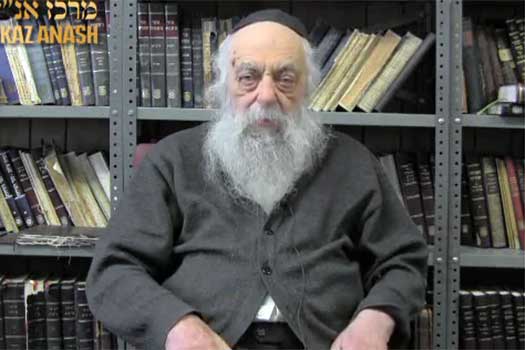

Reb Yoel Kahn: Physical Reward

Due to the overwhelming response and demand from the community, Reb Yoel Kahn agreed to present a weekly webcast on topics that are timely and relevant. This week’s topic is titled ‘Physical Reward‘.

Reb Yoel Kahn, known to his thousands of students as “Reb Yoel,” serves as the head mashpia at the Central Tomchei Temimim Yeshivah in 770. For over forty years he served as the chief ‘chozer’ (transcriber) of all the Rebbe’s sichos and ma’amorim. He is also the editor-in-chief of Sefer HoErchim Chabad, an encyclopedia of Chabad Chassidus.

In response to the growing thirst of Anash for Chassidus guidance in day-to-day life, Reb Yoel has agreed to the request of Merkaz Anash to begin a series of short video talks on Yomei d’Pagra and special topics.

The video was facilitated by Beis Hamedrash L’shluchim, a branch of Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch

Parshas Bechukosai begins: “If you follow my chukos and you observe my mitzvos . . I will provide your rain on time. . and the trees will bear fruit.” Hashem is initiating us here into the concept ofs’char; if we observe His ordinances, He’ll reward us generously.

However, the use of the word “chukos” needs to be addressed. On a simple level, based on the continuation of the possuk, it would seem to be in reference to the observance of mitzvos. Yet, as we know, there’s a distinction between mitzvos which are chukim, those with no apparent logical underpinning, linguistically derived from “chukah chakakti,” “I’ve enacted this decree,” and mishpatim, which are universally understandable; why then is the word “chukos” specifically selected here? It’s possible to explain, as Rashi does, that the word refers here to the study of Torah, but we would still have to assume that those particular laws are the ones being learned, which leads us back to the same problem.

Spiritual Reward

Aside from this question, there is a larger issue raised by many commentaries and classic works: Beyond the physical reward we receive for Torah and mitzvos, there is the spiritual one, which is of much greater significance; learning Torah properly can enable us to experience remarkable divine revelations. Someone of that caliber could ostensibly just be promised that his trees will bear fruit, or, alternatively and more appropriately, that he’ll merit to bask in the shechina’s glow, and that he can partake of that future experience now in some measure; clearly the reward of a Heavenly nature completely outranks anything of physical value. This makes our parsha’s elaboration of the delights of physical s’char, with no mention whatsoever of anything relating to spirituality, rather perplexing.

We could argue that the targets here are people of a more simplistic orientation, and the Torah, which speaks in average terms, was aware that they would not be persuaded by promises of lofty treasures, and considering that the entire point of a reward is to create an effective incentive, it made sense to eschew the spiritual in favor of the physical. But this seems to reduce the Torah’s intended audience. Indeed, the individuals at the very pinnacle of G-dly service are so selfless, that they don’t even care about the spiritual dividends; however in addressing the mainstream, though the majority of Jews might be impacted most by gashmiyus, a plurality would be attracted to the ruchniyus as well!

Where is Life?

To understand the answer provided by the Rebbe, we’ll begin with an analogy. Our souls contribute various powers that animate our bodies, like sight, intelligence, emotions and many others. Each is assigned its own exclusive destination in the body, like sight in the eyes, hearing in the ears, intelligence in our brain; random body parts like our hands and legs won’t do. And the more advanced a certain faculty is, the appropriate body part is of a more refined nature.

Yet our very life force itself is ubiquitous; from our head to our feet, no part of our body isn’t alive. But if you think about it, and you consider that the heart, and no lower organ or limb, contains the emotions, and intelligence, beyond the heart’s capabilities, is confined to the brain, then shouldn’t life itself take up residence somewhere truly elevated? But no, life is everywhere, even in the smallest parts!

The answer is that our functions which are constricted are just that, individual functions, and therefore they only match a particular part of the body. Our brain which is refined enough to be the seat of our mental activity, and is where our brain power must remain aside from the little that’s emitted and impacts our heart. The notion that our hands or feet should interact with our intelligence is absurd, since it follows that our faculties of a particular nature should be assigned dedicated vessels, designed to contain the entirety or at least the emanations from the koach in question.

Life, however, isn’t a detail; it’s the entirety of our existence. A live person is the polar opposite of a dead person, while a foolish man, while not ideal, isn’t less of a human, and the same goes for the blind and deaf, since the things they lack are simply components provided by the soul. Life, on the other hand, is the basis of our being, and is present wherever any element of us is to be found, since everything within us is a part of who we are.

“Ki Heim Chayeinu”

The basis of our existence as Jews is Torah and mitzvos, “ki heim chayeinu,” our very life. And so were we to emphasize the kind of G-dly revelations we could attain through Torah, while true, considering that Torah does contain tremendous heights, and through studying Torah and performing mitzvosproperly we could merit a glimpse, a preview of the divine pleasure experienced in the future, it would not do justice to the fact that this is at the foundation of our very being. A message like that would be more akin to intelligence which, as we described, resides in the head with some impact on the heart, (and is involved to an even further degree with our hands when they acquire the skill of writing), but not down in our feet, since it is only one, individual component, consigned strictly to where it’s compatible. But Torah is more than a vessel for revelation, and it touches at our very essence. And so when a Jew owns a tree, and he studies Torah intensively, it bears fruit. What’s the connection to Torah, you ask? A more accurate question would be: what part of our existence doesn’t have a connection to Torah?

In this light, our parsha’s awareness campaign is resonant with Jews of all stripes. Simple Jews are specifically attracted by the straightforward promise of physical blessings, while to Jews of the loftiest caliber, who don’t need any motivation, this isn’t about being promised a reward at all; it’s an expression of how Torah is so inherent to who we are that nothing about us is disconnected from it.

This also fits with “chukos,” meaning ‘chakika,’ etching, because whereas letters written in ink are additional, not integral, to the paper, letters carved into stone become part of the stone itself. And so “chukos,” in this context in reference to all mitzvos, are so deeply engrained and so inherently a part of us, that the reward they engender is physical. This serves both as a nod to the average person, but primarily as an expression of our oneness with Torah, to the extent that our efforts in Torah study literally result in our trees bearing fruit.