Reb Yoel Kahn: To Love with Kabalas Ol?

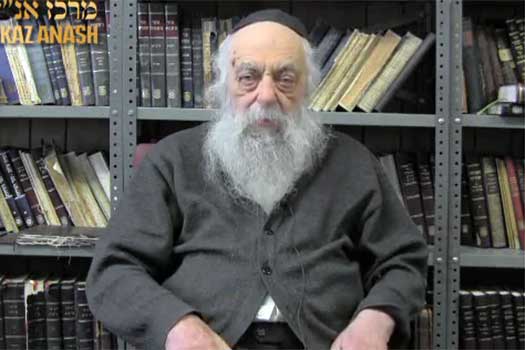

Due to the overwhelming response and demand from the community, Reb Yoel Kahn agreed to present a weekly webcast on topics that are timely and relevant. This week’s topic is titled ‘To Love with Kabalas Ol?‘.

Reb Yoel Kahn, known to his thousands of students as “Reb Yoel,” serves as the head mashpia at the Central Tomchei Temimim Yeshivah in 770. For over forty years he served as the chief ‘chozer’ (transcriber) of all the Rebbe’s sichos and ma’amorim. He is also the editor-in-chief of Sefer HoErchim Chabad, an encyclopedia of Chabad Chassidus.

In response to the growing thirst of Anash for Chassidus guidance in day-to-day life, Reb Yoel has agreed to the request of Merkaz Anash to begin a series of short video talks on Yomei d’Pagra and special topics.

The video was facilitated by Beis Hamedrash L’shluchim, a branch of Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch

Tanya, in chapter 41, quotes the Zohar on parshas behar. Everything about Tanya is precise; a painstaking work of twenty years, there are plenty of Chazal’s statements cited throughout, some without specific attribution, others with a general reference to the work they’re found in, but the Alter Rebbe makes a point here of mentioning that the statement he’s about to quote is in the Zohar ofbehar. The Rebbe therefore concludes that the specificity of this reference contributes to our understanding of the issue at hand.

Yirah: Bad or Good?

This chapter of Tanya discusses the concept that we must have both ahava and yirah, which are generally described as the foundations of the observance of the positive and negative commandments, respectively, as laid out in chapter 4 of Tanya, since love leads us to get involved in things which bring us closer to Hashem, while fear motivates us to avoid committing transgressions.

Now, in chapter 41, the Alter Rebbe adds that even asei tov requires yirah and accepting the yoke of Heaven. It is in this context that he writes at length about how crucial yirah and kabbalas ol are. He bases this on the fact that we’re told “va’avad’tem”, that we’re to serve Hashem as slaves, a relationship which is predicated on fear of the master, whereas being observant out of love does not meet the requirement of avodas eved. Here is where the Zohar in behar is introduced; it says there that “just as an ox has a yoke placed on it first in order that it bring benefit to the world, we must similarly accept the yoke of Heaven first or else holiness cannot dwell within us,” and the specific section ofbehar is explicitly referenced here.

What exactly is this chapter of Tanya trying to establish? Superficially it might seem that the point is that ahava alone without yirah isn’t enough. But we’ve already learned in the previous chapters thatyirah is necessary to keep the urge to commit sins in check, in the absence of which there certainly won’t be a welcome habitat for holiness. What would the novelty be in repeating that?

There’s a parable explaining the earlier point: in order to prepare a residence for a human king, the area must first be purged of even the slightest trace of dirt, and then the space must be filled with tasteful furnishings that are fit for a king; similarly, when creating a dirah for Hashem, we must firstly avoid sinning completely, but then we must follow up with the good deeds which furnish His dirah, and the latter is understandably brought on by the loving urge to be connected to Hashem, while the former requires fear, or else sinning is likely, and even were an actual sin not to occur, the lack ofyirah would make it uninhabitable for Hashem. But what’s the chidush in our chapter?

The Alter Rebbe states here that although love is the basis of doing good, while fear is the deterrent for sinning, ahava alone cannot be the sole foundation of asei tov, and it must also be complemented by yirah. But why did he mention sur mei’ra at all? Considering that we already know the role fear plays, and the fact that it is love which is deficient and must be accompanied by fear, it could have just said “although ahava is the basis of asei tov, it is not enough without yirah”; why mention sur mei’ra at all and how fear is necessary for that, when the point being made seemingly doesn’t concern that?

Submission and Expression

The Rebbe explains that the Alter Rebbe wished to say that not only is an utter lack of yirah no good, but even if there’s fear but it’s concentrated solely on sur mei’ra while asei tov is addressed only by love, then although the prospect of actually sinning has been prevented, the fact that the yirah is restricted to the bad and the ahava to the good is a problem. This is what the Zohar is saying: an ox is harnessed first “in order that it bring benefit to the world;” it isn’t enough that the yoke prevents the ox from kicking, the yirah must be present and underlying the beneficial act of plowing as well. And so the continuation, “or else holiness cannot dwell within us” is telling us that even if there is no risk of sinning due to fear, it’s imperative that the positive acts be fueled by yirah as well.

Why in fact is that the case? The Alter Rebbe explains that we must foremost be an eved to Hashem; in order to develop a connection with Hashem and reveal His G-dliness, there must be bitul, which is the prerequisite to holiness, since he explained earlier in chapter 6 that Hashem only dwells in what’sbatel to Him. What is ahava? When someone loves another, he isn’t nullifying himself, he’s expressing his affection and his desire to connect; yirah is submission, ahava is expression. So when asei tov is consistently motivated by love and the desire to connect with Hashem but lacks an element of fear, it is lacking because there is an absence of bitul, and since holiness is synonymous with eliciting submission, the kedusha is missing as well.

A Humble Mountain

But then we must question what role love plays; we can’t be suggesting that there need be nothing beyond fear behind both sur mei’ra and asei tov, because doing good isn’t associated with being under a yoke, it’s about passion and delight, and so ahava is clearly involved. How then are we suggesting that our acts be driven by love, yet at the same time the role of yirah and kabbalas ol be expanded into the domain of asei tov?

This is why the Alter Rebbe mentions “behar,” mountain. The Gemara states that Sinai was chosen because it was the smallest and the lowest of all the mountains, which alludes to the necessary bitul. But in that case, why use a mountain altogether instead of using a plain or even someplace low? The answer is that a mountain is necessary, yet it must remain small. We must set out to develop love for Hashem, not because it’s our own reaction to Hashem’s greatness but due to Hashem’s command that we love Him, and thus the ahava is founded on kabalas ol.

That’s what Tanya is saying here: we must foremost be a slave and be submissive to our master, and that being the case we do what we’re told, no matter what function is involved; and so if we’re commanded to arouse a feeling of love we do so, and thus bitul and kabalas ol are the foundation ofahava and asei tov, and it is only then that we are worthy of kedusha dwelling within us.