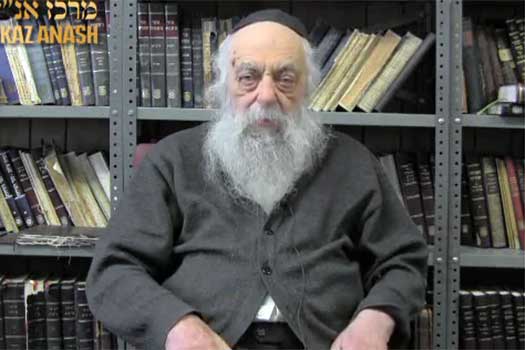

Reb Yoel Kahn: Transforming the Self

Due to the overwhelming response and demand from the community, Reb Yoel Kahn agreed to present a weekly webcast on topics that are timely and relevant. This week’s topic is titled ‘Transforming the Self‘.

Reb Yoel Kahn, known to his thousands of students as “Reb Yoel,” serves as the head mashpia at the Central Tomchei Temimim Yeshivah in 770. For over forty years he served as the chief ‘chozer’ (transcriber) of all the Rebbe’s sichos and ma’amorim. He is also the editor-in-chief of Sefer HoErchim Chabad, an encyclopedia of Chabad Chassidus.

In response to the growing thirst of Anash for Chassidus guidance in day-to-day life, Reb Yoel has agreed to the request of Merkaz Anash to begin a series of short video talks on Yomei d’Pagra and special topics.

The video was facilitated by Beis Hamedrash L’shluchim, a branch of Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch

We count the omer between Pesach and Shavuos, Pesach being when we left Egypt, and Shavuos when the Torah was given. These two events are strongly connected, as the purpose of leaving Egypt was to “serve G-d at this mountain,” matan Torah, and conversely, the Aseres Hadibros begin with “I am Hashem . . Who took you out of Egypt.”

Sefiras ha’omer spans the time between these two events, indicating that this is all one continuum. “U’sfartem lachem mi’macharas ha’shabbos,” we are to do the counting from the morrow of ‘the Shabbos,’ ‘Shabbos’ being Pesach, and so the counting begins immediately after Pesach, and, on the fiftieth day, the seven weeks of counting culminate in Shavuos. This indicates that leaving Mitzrayimconsists of three stages, first the exodus, then sefirah, and finally, the climax, matan Torah.

We also find that Nissan, Iyar and Sivan are specifically a continuation of yetzias Mitzrayim. Although all months are counted from the month of yetzias Mitzrayim, they’re never directly linked to it, whereas Nissan is described as the month “in which you left Egypt,” Iyar is called “the second month after leaving Egypt,” and Sivan is “the third month after the Jews left Egypt.” Thus there are three phases, the miracle of Pesach and yetzias Mitzrayim of Nissan, the sefirah which takes place in Iyar, and Matan Torah in Sivan. What does this mean?

Divine Inspiration

We didn’t contribute anything to yetzias Mitzrayim, it all came from Heaven; we were “eirom v’eryah,” devoid of mitzvos, and Hashem just revealed Himself, and this tremendous revelation drew us and created the incredible arousal which carried us out of Egypt. We were drawn to the extent that we pursued Hashem, “you followed me in a desert,” we chased Hashem without any regard for the logistics. How was that possible? Because Hashem revealed Himself and drew us in. This great inspiration, however, didn’t really involve us.

We can do teshuva in two ways: we can learn seforim about Hashem’s greatness and the terrible damage of an aveira, and when we’ll learn and internalize it, we’ll strongly regret the past and pledge a better future. Alternatively, with no preparation whatsoever, we can be visited by thoughts of repenting. What’s the origin of these sudden thoughts? It’s said that there are various Heavenly announcements which are made daily, calling for teshuva or bemoaning Torah’s degradation, but what are they for if no one can hear them? The Baal Shem Tov explains that our souls are privy to these declarations, and when our souls perceive one, we experience the inspiration for teshuva. But which of these two is greater: the Heavenly call, or engaging in personal study and effort? In truth, both are superior in their own way.

On the one hand, the inspiration which originates in Heaven is better, since no matter how much effort we put into focusing on Hashem’s greatness and the spiritual harm of an aveira, considering that our minds are limited and our understanding is measured, the teshuva which that inspires will be commensurately measured. However, this is only the result of our own work; the Heavenly call we hear isn’t constrained, and it conveys the true severity of the sin, and thus the resulting hisorerus is far greater. But on the other hand, how much are we transformed? We’ve done nothing of our own and remain completely unengaged, so the inspiration might be stronger but it lasts less, because it isn’t tied to our own perceptions. However, when we’re involved and we invest effort, then we might not be as aroused, but it is deeper and holds for longer; our personal involvement results in real internalization.

Internal Change

The same goes for other things. Consider gaavah, the source of all bad traits; how can we rid ourselves of it? There appear to be two approaches. We could start by questioning why we hold highly of ourselves: is it because we have a lot of money? We could then think about how the money isn’t ours, it’s Hashem’s gift and not an indication of our own qualifications, and the reason we’ve received it is for the purpose of dispensing tzedaka, and we could ask ourselves whether we’re utilizing Hashem’s gift properly. Do we possess spiritual wealth? That’s Hashem’s gift too, and we must question whether we’re using it properly as well. In this vein we could persuade ourselves that there’s nothing to be prideful about. Alternatively, we could just note that Hashem despises the haughty and then cease being a baal gaavah. But then we must question whether we’ve really changed, because as long as the latent motive for gaavah is still present, no inspiration will ever help. We can read numerous times that pride is forbidden and how Hashem loathes it, but if we’re still convinced of our greatness, we’ll always remain a baal gaavah.

The same applies for everything else. There’s only one way to eliminate our desire for worldly pleasures: we must focus on how it isn’t truly good, and is only appropriate for an animal, that there’s nothing good aside from G-dliness, “taamu u’r’u ki tov Havaya,” and the more we internalize this, the greater success we’ll have at reducing our enjoyment of physical pleasures. But when we never comprehend that materialism isn’t desirable, and we accept that it’s wrong simply because Hashem doesn’t like it, then the inspiration cannot lessen the gaavah or the taavah, since we never changed our inner perception of what we consider to be good.

“The Day after Shabbos”

This gives us insight into the difference between the two steps of yetzias Mitzrayim. The first was a tremendous Heavenly arousal which involved no effort, and it resulted in incredible devotion to the extent of throwing care to the wind and following Hashem into the desert, yet the Gemara states that the “zuhama,” the spiritual contamination which originated in Egypt, stayed with us until matan Torah.

How could both be true at the same time? We now know based on our earlier discussion that it’s possible to be engaging in mesiras nefesh with no regard for ourselves, yet our individual traits remain unchanged. To uproot gaavah we need to realize that there’s nothing to be prideful about, and to root out our desires we must recognize that they are worthless. So long as that doesn’t happen, those bad traits will endure. We can be expressing incredible devotion to Hashem, while at the same time ourmidos, beginning with gaavah which is the root of our faults, remain unaffected, the “zuhama” doesn’t leave.

And that’s why “u’sfartem” immediately follows; after yetzias Mitzrayim, being inspired isn’t sufficient, we must work on improving our midos, one week for each of the seven, with each week dedicated to all seven sub-midos within the seven. Yet as we successfully alter ourselves, we return to the problem of the inadequate range of our human efforts; we cannot reach beyond our limited capacity.

And that’s why it says “u’sfartem lachem mi’macharas ha’shabbos.” “U’sfartem lachem” represents endeavoring to improve oneself, “u’sfartem” in the sense of ‘sapphire,’ making the “lachem” shine through illuminating our midos. Yet, the progress when working alone isn’t much, and that’s the point of “mi’macharas ha’shabbos,” sefirah is an outgrowth of yetzias Mitzrayim. Hashem didn’t merely inspire us to follow Him, He also infuses our avodah of sefirah with the ability to reach greater heights, and so the two approaches complement each other.

We then reach the third element, which is the climax of yetzias Mitzrayim, matan Torah, when “those above shall descend below, and those below shall rise above,” together, the Heavenly energy reaches us here, and then we, “those below,” can transcend our limitations in our avodah; the Midrash states that Hashem affirmed the need for the spiritual revelation of har Sinai to occur first, and this in turn grants us the ability to reach heights without limits.

Three Steps

We mention yetzias Mitzrayim every day, and we similarly undergo the three stages described above daily. As soon as we awaken, we say modeh ani. Even before negel vasser, when we still can’t learn, there’s the general arousal of modeh ani; we recognize the melech chai v’kayam Who has returned our soul, and we surrender ourselves to Him. That’s the yetzias Mitzrayim, following Hashem in the desert.

But that’s not enough: “u’sfartem,” we must cleanse ourselves, learn some Chassidus before davening, and by the time we conclude the pesukei d’zimrah, we’re ready for “v’ahavta,” to love Hashem with both our souls, with even our animal soul being included in the experience. The Heavenly inspiration alone will have no effect on it; and so not sufficing with hodaah, we go through davening until we reach ”v’ahavta.”

We then finally arrive at shemoneh esreh, where the two are combined; yetzias Mitzrayim achieves its purpose, “serv[ing] G-d at this mountain,” and “in the third month after the Jews left Egypt [we] arrive at Sinai,” the two together.