Snapshots from the Life of Aaron Mendelsohn

By Dovid Zaklikowski, HasidicArchives.com

Aaron “Harry” Mendelsohn passed away on the 3rd of Nissan (April 8, 2019), almost one hundred years after his maternal grandparents arrived in Fayetteville, North Carolina, from Europe. The family was among the founding members of the local Beth Israel synagogue.

Aaron was raised in a traditional Jewish home. He once told how, at age five, he ate ham by accident. “I ran outside of school and threw up.” Almost five decades later, he said, “I still remember it.”

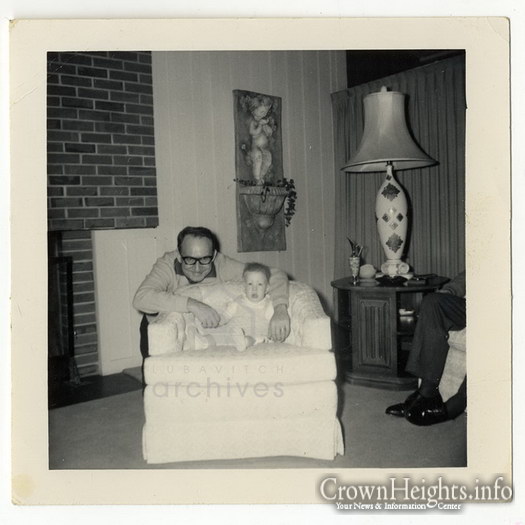

His mother passed away of natural causes just before Aaron’s first birthday; his father survived her for only six years. “On a Saturday night my father came home from a night out,” he wrote in 2018, “and went to his bedroom as he wasn’t feeling well. A short time later, paramedics rushed up to his room and wheeled him out on a stretcher in front of his seven-year-old son. That was the last time I saw my father alive.”

Aaron cherished his few memories of his parents. He was sure they were watching and praying for him from above. “My life as an orphan began then,” he wrote, “and my childhood and my life changed drastically.”

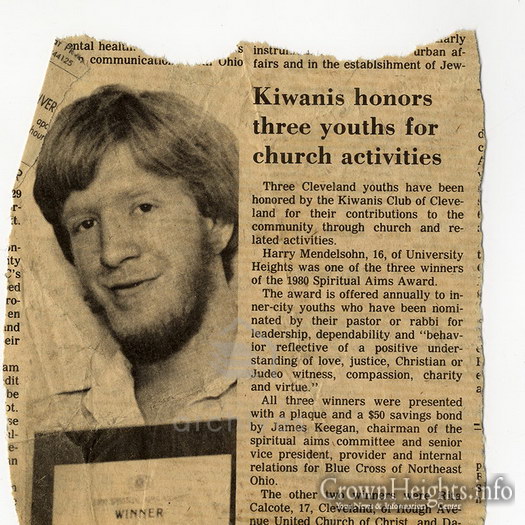

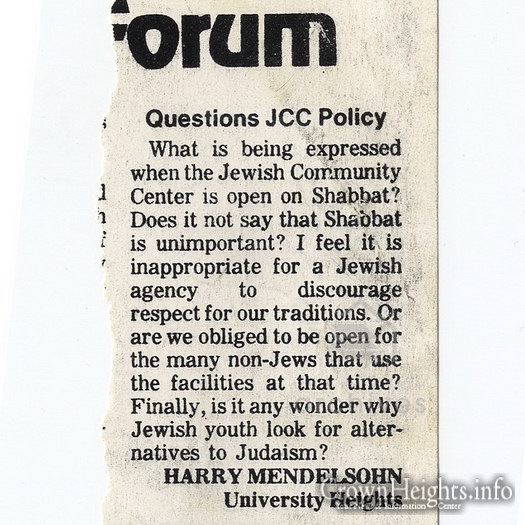

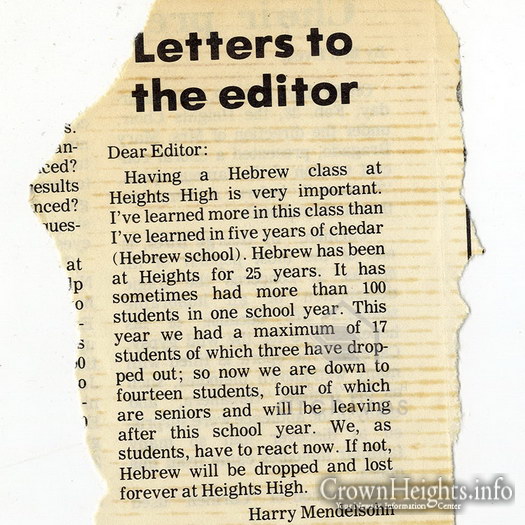

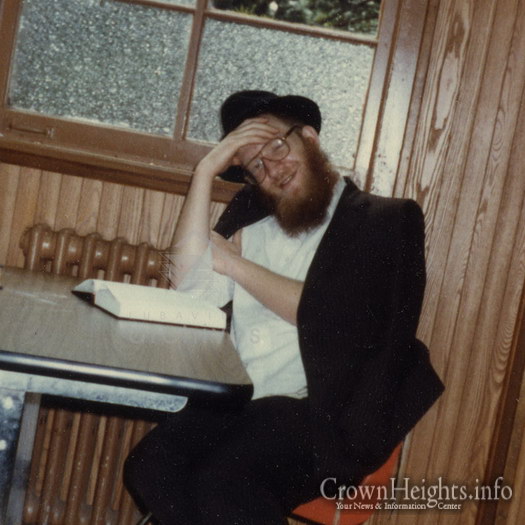

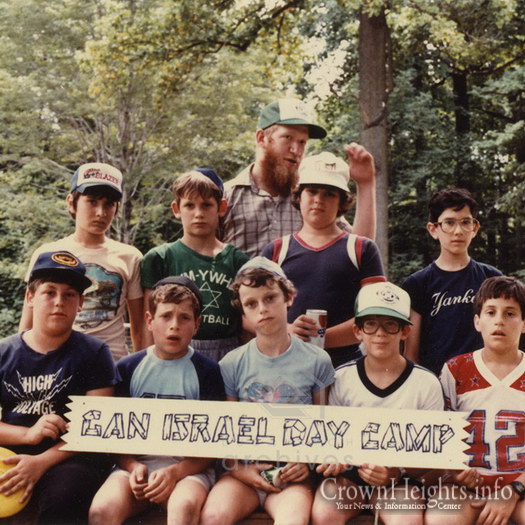

His maternal grandmother lived with Aaron in the family home in Fayetteville until his early teen years. On campus in Cleveland, Ohio, Aaron encountered Chabad. After he graduated, he attended the Rabbinical College of America in Morristown, New Jersey, where he received rabbinical ordination. Later, he moved to Kfar Chabad, Israel, and pursued advanced rabbinical studies.

In the late 1980s, Aaron settled in New York and opened Mendelsohn Press, a typesetting and graphic design firm. Over time, the business evolved into a printing house specializing in Jewish publications and developed a substantial clientele. He also pioneered the new typography of the Talmud, publishing in 1995 tractate of Baba Metziah. Today is the norm for all editions to have new typography.

Still, Aaron never made it big. “I’m not a money-hungry guy,” he wrote. “I’m not poor. I pay my bills.” If he needed money, he added, “G-d ‘calls’ [one of my clients] and he has a check for me.”

He explained that his attitude was based on Chassidic teachings. “G-d gives a person money. Work is only a vessel, and the more you help other people, the more you make.”

He added, “I just believe. I have nothing else in my life.”

Aaron had a deep love for the Rebbe. At home, he listened to tapes of the Rebbe’s talks for hours, a habit he developed in his twenties. He described an early job for a Williamsburg bookbinder who had a temper. To muffle the man’s yelling, Aaron brought a boom box to work and played tapes of the Rebbe’s farbrengens. “I loved it.” When his boss objected, “I told them, ‘If I can’t play them, I quit.’”

His friends knew they could rely on him for emotional support. “If you ever want to chat,” he’d say, “I’m here.” They remember him as good natured, “a teddy bear,” a kind-hearted, devoted friend, above all, a mensch.

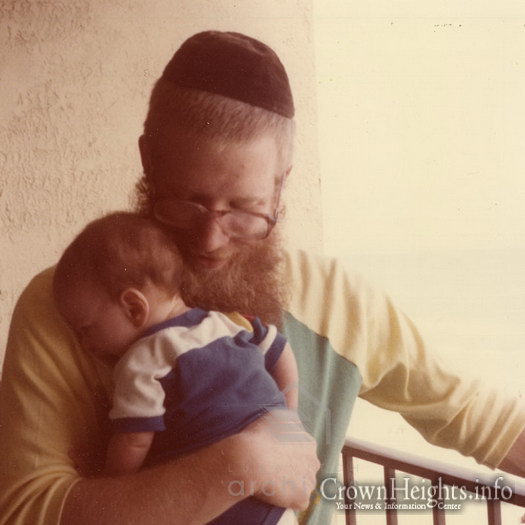

To his family, he was a playful, devoted father and uncle. Navigating the roads by memory and ignoring the instruction of his GPS, he took them on a yearly pilgrimage to Fayetteville and Myrtle Beach, where his parents were buried, before the High Holidays.

He regularly made the trip to New Jersey to take his nephews to nearby amusement parks and joined them on the rollercoasters and rides. The sole observant Jew in his extended family, he added the expression Baruch Hashem to their lexicon and proudly wore his Chassidic garb to family events.

Recently, he had some stomach trouble and suffered a burst appendix. During the two weeks he spent in the intensive care unit, the hospital staff was impressed by the affection of his family, and his family was impressed by the support and concern of his friends, customers, and the Chabad community as a whole.

Perhaps more than anything, the quality that defined Aaron’s life was faith. When a friend wrote to him a week before he became ill, expressing concern about paying back a loan, Aaron replied, “Hashem will help.”