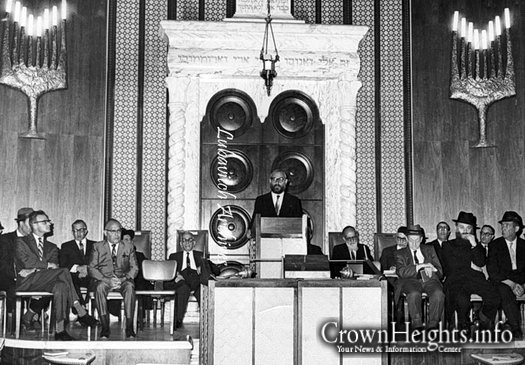

A Chabad Rabbi who Led Sephardic Congregations

Rabbi Abraham Hecht, a Chabad-Lubavitch rabbi who served as the spiritual leader of Sephardic congregations in North America for more than 65 years, passed away Saturday night at the age of 90. For many years he the was vice president of the Sephardic Rabbinical Council, president of Rabbinical Council for Syrian Jewry in North America, and president of the Rabbinical Alliance of America. Beloved by his congregants, he built Congregation Shaare Zion in Brooklyn, N.Y., into the largest Sephardic congregation in North America.

“I am still very much identified with Chassidus,” Hecht wrote in his 2006 autobiography, using the Yiddish word referring to the Chassidic way of life, “which has shown me the proper way of life in the American wasteland. My situation might have appeared interesting and bizarre, yet I found the description of a Lubavitcher Sephardic Rabbi quite comfortable.”

Born in 1922 to Shia and Sorah Hecht in Brooklyn, N.Y., he studied at the Rabbi Chaim Berlin and Torah Vodaath schools. The young lad was imbued by his parents with love of Judaism and Jewish scholarship. “The American soil resisted their efforts at every turn [to maintain Jewish tradition],” Hecht said of his parents’ struggles, “but their roots were only strengthened by the adverse conditions.”

Their home served as a focal point for assisting others, and was a center for many charitable endeavors. Rabbis from Europe and the Holy Land would often make the Hecht home their base during visits to New York.

His father would personally prepare the room where the guests would sleep, Hecht said, although he and his siblings were ready to do it themselves. “He never considered it a burden; [he] felt honored to service his righteous guests.”

Hecht once recalled that on the Sabbath “my father used to insist on giving up his own seat at the head of the table in deference to a rabbinical guest.”

One of his most profound memories from childhood was being awakened one night by the sound of his maternal grandfather, Shialeh Auster, crying in deep prayer. “I was awakened by the sounds of heart-wrenching sobs. His broken cries tore at my heart.”

While studying at the Torah Vodaath school, he and his siblings became greatly influenced by Rabbi Yisroel Jacobson, one of the original pioneers of Chabad-Lubavitch in the United States. The brothers joined chassidic gatherings at the Jacobson home, where they would hear profound discourses on life, sing heartwarming chassidic melodies and listen to inspiring stories.

The students were free to open their hearts and ask their most provocative questions on faith and on life in a free democratic country, where keeping Judaism was a great challenge. “With an unusual amount of patience and understanding,” Hecht recalled, “Rabbi Jacobson resolved their problems and cleared up their confusion.”

Off to Poland

In the summer of 1939, Hecht and five other students decided that they wanted to head off to the Chabad-Lubavitch yeshiva in Otwock, Poland. There they could be close to their spiritual leader, the sixth Chabad rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory, and would be able to take part in listening to his scholarly discourses in Chabad philosophy, something they had heard much about from Jacobson.

With the blessing of his parents, Hecht set off for Poland in early August on the Ile de France. At the harbor, many Chabad-Lubavitch disciples broke into spontaneous dance. They never believed that “spoiled” American students would find the willpower to go to impoverished Poland to study Judaism and acclimate themselves to the rigorous curriculum of yeshivah students there.

On the way they stopped in Paris, France, where they met Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the son-in-law of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak and future leader of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement. “At first glance, I sized him up as a young man in his thirties, with a nice beard and gray hat,” Hecht recalled in his autobiography, My Spiritual Journey. “Upon further inspection, I noted the piety and purity streaming forth from his friendly, welcoming countenance and the exalted level of kedusha [holiness] he had reached at such a young age.”

Hecht writes that they felt privileged to be in his company before the train carried them past towns and cities in various countries. As the students were coming off the train, the future rebbe “stood on the steps of the train as he patiently and warmly spoke to us. He told us of the great zechus [merit] we had to go to Otwock to be in the presence of the Rebbe and to become his students. He blessed us and wished us success in our studies.”

Upon his arrival in Otwock, Hecht recalled a sight that astonished the Americans, as he saw four hundred students swaying diligently over their Talmuds and their intense discussions of scholarly Talmudic subjects. “The air was soaked with an intense concentration coupled with an unquenchable thirst for knowledge and true love of Torah [study],” he wrote.

But their time in Poland was short-lived, as the Germans began to bomb Poland. With the help of a courageous representative of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee they made their way to Riga, Latvia, from there to Sweden and then to the United States.

On March 19, 1940, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak reached the shores of New York. Even as he tirelessly campaigned on behalf of European Jewry, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak also set forth a plan to build Jewish observance in the United States. Hecht joined nine other students in the first Chabad school in the basement of the Oneg Shabbos synagogue in the East Flatbush neighborhood in Brooklyn, N.Y.

After graduating in 1942, he established Chabad day schools in Worcester, Mass., New Haven, Conn., and Buffalo, N.Y., something that was novel during those years. He also served for six months as the director of the Chabad School in Newark, N.J.

In June 1944 he married Libe Grunhut and moved to Dorchester, Mass., to establish a Jewish day school in the city. After several doors were slammed in his face, Hecht realized how difficult it would be to open a Jewish day school in that city.

He wrote a painful letter to Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak saying how embarrassed he was by the ordeal. “This is no job for a rabbi unaccepted in an out-of town city,” he wrote, expressing his feelings of depression and humiliation.

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak wrote back to him that the feeling of shame and sorrow came from a place of haughtiness and misplaced pride.

Hecht says the letter gave him a new perspective on being a Jewish leader. “My entire disposition [underwent] a quick transformation. Why did I imagine that the praiseworthy endeavor of establishing a [Jewish school] would proceed smoothly and [on an] express track? Every goal worth attaining was preceded by a path strewn with obstacles and hardships.”

After twelve months of hard work, the school had enrolled 120 students in five grades.

A newly arrived immigrant without her family, Mrs. Hecht felt isolated in the small Jewish community, so they headed off during the school’s summer vacation to the Fleischmanns bungalow colony in the Catskills, the famed Jewish vacation area in New York State.

A Rabbi in Foreign Territory

Many Jews of Sephardic descent also spent their vacation time at the bungalow colony. Hecht followed the customs of Chabad-Lubavitch, which was founded in Europe and whose roots are in Ashkenazic Jewry. His customs differed greatly from those of Sephardic Jews, who for the most part descend from Spain, North Africa and the Middle East.

At the bungalow colony, the Ashkenazic and Sephardic communities lived divided but peaceful lives. They used the synagogue at different times, and for the most part kept their distance from each other. “One bright, sunny afternoon,” recalled Hecht, “several members of the Sephardic community approached me with an odd request.”

They asked him if he spoke English, and if so, could he give the Sabbath afternoon lecture? He agreed, and spoke at length to the 50 men and women who were gathered. Feeling that his words were resonating with the crowd, he went on for a while with his spirited speech. The community congratulated him on his speech, and soon offered him a position in the Syrian Jewish community.

In October he accepted the position of youth rabbi at the Bnai Magen Davidsynagogue in the Bensonhurst neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., and headed their school. He immediately set out to work on improving the day school and engaging the youth in the Jewish community.

Soon, he had more than 400 youth group members praying in a designated room at the synagogue. He engaged the youth as young Americans whose parents did not understand their challenges and who often did not speak their language. As he became acquainted with the Sephardic customs and community, he developed a fluency in Arabic, which made it possible to forge relationships with the older Sephardic community members and with new immigrants.

After accepting a rabbinic position in a Brooklyn synagogue in 1956, he wrote to the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory, that he was successful in starting daily prayer services. “When seeing the ease of your success in your efforts,” the Rebbe responded, “how much more so that your greater efforts in strengthening Jewish practice will be successful.” The Rebbe then suggested that the congregants should be served some refreshments after daily prayers, and that every day another congregant should speak for a few minutes on a Torah-related topic.

Hecht later became the rabbi of Congregation Shaare Zion, which he led to grow to over 3,500 families, and which today is the largest Sephardic congregation in North America.

“Although there wasn’t a trace of Sephardic ancestry in the roots of my extended family tree,” he would later write, “I feel an inexplicable affinity with the community I had learned to lead and understand.”

The Jews in Syria

Hecht said about his short time of living in Europe at the onset of World War II that upon his return to the United States he “blissfully breathed the air of freedom and safety, promising myself that I would never again take the blessing for granted.”

When he learned of the severe persecutions that Jews in Syria were enduring after Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War in 1967, Hecht felt he had no choice but to spring into action, to help others gain the taste of freedom that he had come to appreciate.

He made an appointment to meet George Baroudy, the Saudi Arabian ambassador to the United Nations, who in turn gathered delegates of Arabic countries to meet with Hecht. In fluent Arabic, Hecht requested that those who attended should urge their governments to place the Jewish population in Syria under the protection of the Red Crescent, and that those Jews who wanted to emigrate should be allowed to do so immediately.

While not all the community’s requests were granted, Syrian Jews reported that shortly after their meeting the Syrian president issued a strict warning against attacking any Jew or Jewish home.

Over the years he continued to use all the political weight he could to pressure Middle Eastern countries to protect the Jews in their countries. He also arranged for Jewish ritual items to be shipped to Middle Eastern nations, including much needed prayerbooks and other Jewish books in Arabic.

By 1998, years of effort by Hecht and others paid off, and the Jewish population of Syria was permitted to leave the country. “It had taken many decades of work,” he wrote, “but we had finally been privileged to welcome our suffering Syrian brethren to an existence virtually untainted by anti-Semitism and crime.”

Rabbi of the House

“Rabbi Hecht has worked tirelessly and with boundless energy on many worthy projects,” former U.S. congressman Stephen J. Solarz told the House of Representatives in 1975, “most notably to secure emigration rights for Syrian Jews. Rabbi Hecht has exhibited noble leadership in his organizing endeavors tempered with a humanistic dedication…his inspiration of courage and humanity.”

He said of Hecht’s educational projects: “In setting up educational centers, classes, lecture series, and numerous scholarly endeavors, he has demonstrated his ability to organize and implement educational programs of the highest caliber.”

Hecht, a great Talmudic scholar and rabbinic figure, accepted many positions with substantial rabbinic duties and little compensation. “They required boundless amounts of energy and attention for many long years,” he wrote about his many rabbinic duties. “Strung together on the chains of time, these difficulties and achievements formed an awesome string of valuable gems.”

“He was involved in many Jewish activities and rabbinical duties in all areas of Judaism,” says Rabbi Herschel Kurzrock, dean of the rabbinical court of the Rabbinical Alliance of America. “Yet he cohesively worked all of them.” He adds that Hecht’s greatest virtue was that not only did he accomplish so much himself, but he also “was able to influence people to accomplish on behalf of Judaism.”

Hecht authored many scholarly articles, and published several volumes of his sermons. At the behest of the Rebbe, he encouraged his rabbinical colleagues to publish their scholarly writings. As a result, the Rabbinical Alliance published many scholarly volumes under his leadership.

Several times Hecht delivered brief benedictions at the opening sessions of the House of Representatives and the Senate. Solarz wrote to him once that “it was really good to have you with us here in Washington a short while ago. I’ve gotten so many favorable comments from my colleagues on your prayer that I think we could elect you, if you’re interested, as the permanent Rabbi of the House when we convene next year.”

The Rebbe requested that Hecht speak about the importance of the nations of the world adhering to the Seven Noahide Laws, and—if it would be possible—to speak to the United Nations on this topic as well.

“Ruler of the universe,” he said in one prayer in the House of Representatives, “we express our deep gratitude to you or the miracles of the civilization we call America. The ideals of liberty, equality and personal freedom, the bedrocks of our society, serve today to millions throughout the world as the most desirable virtues of government.”

“Rabbi Hecht was a leading factor in helping build our great community,” says Morris Baley, a prominent member of the Syrian Jewish community. “He was our intellectual leader, and the force behind our community’s need to move forward. He had an understanding of how Judaism must be part of our modern society. He reached out to our community lovingly, creating a society of love and inclusivity.”

Hecht is survived by many children and grandchildren who serve as Jewish leaders, educators and Chabad-Lubavitch representatives across the globe. “It is my hope and prayer,” he once wrote, “that the younger generation will continue to practice, to teach and inspire countless hundreds of thousands in their important positions in their respective communities, as they serve the Creator according to the teachings of the Lubavitcher Rebbes.”