Ami Magazine Features Spread on the Rebbetzin

She was not in the public eye. Yet, the Lubavitcher Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka’s inspiration is widespread—a result of her quiet ways and nuances of influence.

Most people in the community did not know her. Occasionally, someone would catch a glimpse of her profile as her car passed in the street. Her husband was the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, zt”l. The Rebbe succeeded his father-in-law as rebbe in 1951, and directed Chabad-Lubavitch’s growth from a small community of Russian refugees trying to rebuild after the Holocaust to a world-wide phenomenon that has affected practically every Jewish community in the world. Rabbanim from diverse communities, foreign statesmen, spiritual seekers, scholars, the curious, and the desperate all came to see him. The Rebbe was a prolific letter writer, responding to the thousands who contacted him, and taught Torah to his Chassidim for hours on end during Shabbosim and yomim tovim, and on certain special days throughout the year. Throughout the decades of his very public life as rebbe, however, his wife Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka, zt”l, remained starkly out of the limelight.

There is a picture of Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka watching a Lag Ba’Omer children’s parade in the early 1980s. The photograph depicts a brick house, a tree obscuring the rather large window in the front. The slatted blinds in the window are slightly raised, and a small figure can be hazily seen, sitting in a chair. The three loudspeakers that amplified the parade in the bottom left of the photo are more prominent than the Rebbetzin’s figure. The obscure figure of the Rebbetzin in that photograph perhaps expresses her life as the partner to the leader of one of the most influential and dynamic movements in the post-War Jewish community. She was always there, right where it was all happening, but out of the public view by her own deliberate design.

Today, 23 years after her death, her name is ubiquitous in Chabad. Practically every Lubavitch family has a Chaya Mushka. Countless institutions are named after her. The annual International Lubavitch Women Emissaries Conference—or the Shluchos convention, is held during the anniversary of the week of her passing in Shvat. There is an irony in the fact that, after her death, she was accorded with the public recognition she actively avoided her entire life.

Reticence speaks louder than words

The Rebbetzin remained a mystery even to those who knew her. Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky was a member of the Rebbe’s staff since the 1950s, near the beginning of the Rebbe’s leadership, and was present at many pivotal junctures of Chabad history. He heads several Chabad organizations, and was later named the executor of the Rebbe’s estate. Despite his proximity to the Rebbetzin and Rebbe, he said he was never able to truly grasp or know either of them. Both of them were incredibly private individuals who never shared anything personal beyond what was absolutely necessary, as if their own needs and feelings were completely unimportant. Despite this enormous humility, however, their regalness and wisdom shone through.

Twenty years after her passing, Jewish Educational Media, an organization that specializes in restoring media archives and recording oral histories related to Lubavitch, released a 75 minute DVD called The Rebbetzin in 2008, featuring excerpts of interviews with several people who knew her. The narrator on the film noted her extraordinarily private nature: “Because of her modesty, it is difficult to learn about her life. Those who knew her are still wary about breaching her privacy. Many interviewees would not share experiences they considered too personal.”

The Rebbetzin did not confide in others, and her extreme reticence to talk about herself, a central aspect of her personality, frames any attempt to understand her. She was a deep woman, with many dimensions, able to relate to all kinds of people and talk wisely about all kinds of things, yet “you always knew that there was something more to her,” Rabbi Krinsky summarized. When the Rebbetzin went to shul, she sat in the last section, where she was not noticed. She did not go to farbrengens (Chassidic gatherings)—but only listened over the phone when live hookups became available.

When the Rebbetzin would call the Rebbe’s office or a local store to arrange for a delivery, she identified herself simply as “Mrs. Schneerson from President Street.” She once called the local seminary, trying to reach the granddaughter of a friend who came from London to study in Crown Heights. The administrative office, citing school policy, said that students could not be called out of class. The Rebbetzin politely hung up without saying who she was, and found another way to reach the girl.

Many use terms connoting majesty, such as regal, aristocratic, and gracious, to describe her bearing. Mrs. Louise Hager, who met the Rebbetzin for the first time when she was 14, vividly remembers every detail of her first meeting. The Rebbetzin dressed elegantly and simply; her refined makeup was always meticulously applied. When a family friend, Rabbi Lew, went to meet the Rebbetzin with his kallah and future in-laws, the Rebbetzin served punch in tall crystal glasses with glass straws. While pouring a drink, Rabbi Lew accidentally spilled the bright punch all over the white tablecloth. The Rebbetzin delightedly exclaimed, “A siman bracha!”

Regal, she was

Mrs. Leah Kahan, a distant relative of the Rebbetzin who had a close relationship with her, agreed to share with me some of her experiences with, and memories of, the Rebbetzin. When I pressed Mrs. Kahan for specifics about the Rebbetzin’s daily life and interests, she couldn’t, or perhaps wouldn’t, tell me. “Didn’t any of these details come up in conversations with her?” I asked. Mrs. Kahan responded, “The Rebbetzin made you talk about yourself.”

I met with Mrs. Kahan in her living room. Her husband is Rabbi Yoel Kahan, the Rebbe’s “tape recorder” (Rabbi Kahan headed the group of chozrim, those who remembered the Rebbe’s deep Torah talks on Shabbos and transcribed them after Shabbos) and the editor of Sefer Ha’Erkim, an encyclopedic work of Chassidic concepts. I almost expected her home to resemble a research library. I imagined stacks of sefarim and sheets of paper covered in hurried script. Instead there were dried flowers in vases, pottery on shelves, and a few books. Mrs. Kahan told me that the tall, green potted plants near the window that almost reached the ceiling were given to her by the Rebbetzin. Speaking of her memories, she was at turns wistful and intent, almost stern in trying to explain to me just how extraordinary the Rebbetzin was, occasionally thumping her chest in emphasis. Mrs. Kahan had prepared a bottle of Snapple and a short stack of plastic cups, and offered me a drink. Picking up a cup, she laughed, “The Rebbetzin would never serve you out of plastic.” She put the disposable cup back down, took out a stemmed glass from her china closet, and poured a drink for me.

The Daughter of the Rebbe

Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka (Moussia) Schneerson, zt”l, was born in 1901, in Babinovitch, a city near Lubavitch. She was the second of three girls. Her grandfather, Rabbi Shalom Dovber, known as the Rashab, was the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe. He telegraphed her parents, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak and Nechama Dina, to wish them mazel tov, and said that she should be named Chaya Mushka, after the wife of the third Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel, known as the Tzemach Tzedek. Raised in a Chassidic court, she was intimately aware of the strains and public nature inherent to the role of a rebbe and his family. With the eruption of World War I, life in Lubavitch drastically changed and, in 1915, she and her family moved from Lubavitch to Rostov. This was the first of a series of relocations, as the Rebbe’s family searched for a safe physical haven. Her grandfather, the Rashab, passed away in 1920, and her father, Yosef Yitzchak, assumed leadership as the sixth rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch. Chaya Mushka had a close relationship with her grandfather and helped care for him when he was ill. Perhaps indicative of his respect for her intelligence and level of education, he left some Chassidic classics to her in his will.

As rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak directed numerous underground activities and institutions to combat the communist attack on religious life. Chaya Mushka participated in his work in crucial ways. In one instance that became subsequently known, she personally smuggled food and supplies to a yeshiva that her father supported, the Navardok Yeshiva, at tremendous personal risk. When her father was taken away by the Soviets, he gave his power of attorney to her. Her accuracy, composure, keen perception, and intelligence greatly helped her father.

These aspects of her personality were observed by friends and acquaintances from later periods in her life. Mendel Notik, who assisted in her household years later as a young teenaged student, noted her punctuality and accuracy with household invoices. Mrs. Leah Kahan and Mrs. Hadassah Carlebach remarked on the understated manner in which she expressed herself, eloquently and without exaggeration. Both noted her lack of the use of superlatives.

In 1924, the family moved again, this time to Leningrad. A few short years later, in 1927, the Rebbetzin’s father was arrested by the NKVD for his underground efforts at keeping Yiddishkeit alive. Chaya Mushka cryptically alerted her future husband—“Schneerson, guests have come to visit us!” He was successfully able to warn others to lower their profiles and begin an international campaign for Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s release. Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s harsh sentence was commuted to exile, and Chaya Mushka accompanied her father to Kostrama. He was released on the 12th of Tammuz, and, after continues threats of re-arrest, the family reluctantly moved, once again, to Riga, in what was then still independent Latvia. Before they moved, Chaya Mushka became engaged to a distant cousin, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson.

Bound to the Jewish People

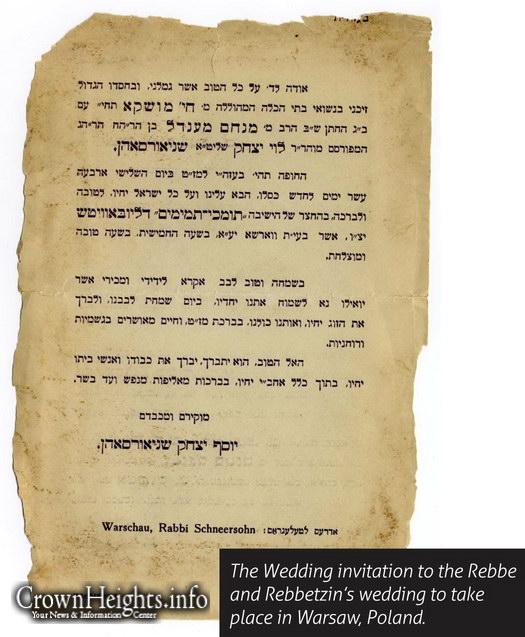

After enduring extraordinary hardship in both leaving Russia and settling in Latvia, the Rebbe tried for many months to gain permission from the Soviets to allow the chosson’s parents to attend the wedding. Subsequently, after waiting for enough funds to actually put on a large and festive wedding, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak arranged for a “Rebbeshe” wedding for Rabbi Menachem Mendel and Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka on 14 Kislev, 1928, in Warsaw, Poland. Thousands of Jews greeted her family at the Warsaw train station, and surrounded the wedding hall. Ushers stood at the entrances and only those with official invitations were permitted to enter. Twenty-five years later, while speaking to Chassidim, the Rebbe referred to his wedding day as the day that “bound me to you, and you to me…,” referring to his induction to his father-in-law’s life as a rebbe via his marriage to his daughter.

After their wedding, R’ Menachem Mendel and Chaya Mushka moved to Berlin. Chaya Mushka took several courses at the Deutsche Institute, while her husband studied mathematics and philosophy. Eyewitnesses relate seeing the Rebbe go to mikvah daily, deliver shiurim in Torah, and, overall, spend his time engrossed in Torah. The Rebbe’s own notebooks from that time convey a mind deeply engaged in learning all aspects of Torah. One eyewitness related chancing upon the Rebbe in his apartment one afternoon wrapped in tallis and tefillin, learning Talmud Yerushalmi. However, the only person with whom the Rebbe shared any of this life was his Rebbetzin.

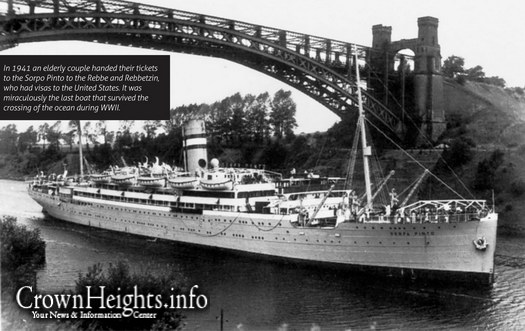

The couple could not stay in Germany long. In 1933, they moved again, to Paris. Seven years later, they fled Vichy France, to Nice. The Rebbetzin subsequently confided to someone a number of the close calls they had lived through during the war, how she would prepare food and secure other necessities for the Rebbe, and the lengths to which the Rebbe went—to the point of immense personal danger—for even an obscure hiddur mitzvah (enhancement of a mitzvah). They finally set sail for America in 1941, on the last passenger ship to cross the Atlantic. Her father was already there, he arrived in the United States one year earlier, in 1940. Upon their arrival, her father appointed her husband director of three new institutions he created to begin the program of Jewish outreach on these shores.

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak passed away in 1950, on 10 Shvat. Exactly one year later, his son-in-law Rabbi Menachem Mendel assumed the leadership role as rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch. Rabbi Krinsky was a young student then and recalls that the “Rebbe was reluctant to take the helm of Lubavitch, and certainly did not show any outward manifestations of taking leadership.” He added, “In the early months, [one] could hardly see a change in his routine. They say it was the Rebbetzin who convinced him that if he didn’t assume the helm of Chabad leadership, it would disintegrate.”

Many of those who knew her emphasize the extreme sacrifice this entailed for the Rebbetzin. Rabbi Lew contextualized the Rebbetzin’s sacrifice in historic dimensions. “She was the person who understood why the world needs the Lubavitcher Rebbe, and gave him to the generation,” he said.

“She must have felt the pain and loneliness, and the discomfort sometimes,” Mrs. Kahan said. Despite that, she hid her discomfort from her husband, the Rebbe, not wanting to distract him from his important work. Mrs. Kahan mentioned that one time the Rebbetzin broke her hand, but hid it from her husband. “She gave the Rebbe to the Chassidim…every day of every week.”

As the Rebbe’s wife, the Rebbetzin was the Rebbe’s ultimate support. Some observers point out that the two shared many characteristics. The Rebbetzin waited up for her husband every night until early hours in the morning, and that could be anywhere between 1:00 to 5:00 AM, when they would eat together and share their days. “You know, my husband comes home very late,” the Rebbetzin told Daniele Lassner, who would visit the Rebbetzin with her parents. “He sometimes comes home [at] two, three in the morning. And when he comes home, I am going to have so much to say to him….”

The Rebbe made sure to drink tea with the Rebbetzin every day. According to his cardiologist, Dr. Ira Weiss, the Rebbe was as meticulous in adhering to their daily “tea party” as he was in putting on his tefillin. The Rebbetzin’s friends and acquaintances all note her relationship with the Rebbe as being very “natural” and built on enormous mutual respect—the way she said “we,” the reverence and warmth with which she would refer to the Rebbe as “mein mann—my husband.”

The Rebbe knows

When the Rebbe suffered a heart attack in 1977, the Rebbetzin’s support of his wishes turned crucial. It was Shemini Atzeres. Rabbi Krinsky remembers that year’s Tishrei as a very strenuous one. On Hoshana Rabbah, the Rebbe stood for hours and gave out lekach (honey cake) to thousands of people. The Rebbe went home for just a few minutes; Rabbi Krinsky doesn’t know if he even had time to take a drink.

Hakafos took place after maariv. The shul was packed. The Rebbe watched hakafos from his place of prayer and energetically encouraged the singing. One year, the Rebbe suddenly turned ashen, stopped clapping, and took hold of his chair. The minhag was that the Rebbe danced with the first sefer Torah for the first hakafa, and the first sefer Torah of the seventh hakafa, along with his brother-in-law, Rabbi Shmaryahu Gourary. The Rebbe was in excruciating pain. He finished hakafos, said aleinu, walked upstairs, and went into his room.

There were four doctors there for Shemini Atzeres. None of them were cardiologists and they could not determine what was wrong. All of them concurred that the Rebbe should have something to eat and drink, which the Rebbe refused to do outside of a sukkah. Within 10 minutes, the Rebbetzin met her husband in the sukkah; she had arrived from her home on President Street. The Rebbe made kiddush on wine and ate some cake for makom seudah (the place of the meal). The Rebbe’s assistants called four different cardiologists, who all arrived within an hour or two. They all said that the Rebbe had experienced a very serious heart attack, and must go to a hospital immediately. The Rebbe was adamant that he remain in 770. Someone brought a bed into the Rebbe’s room. One doctor who worked in the Brooklyn Jewish Hospital, a local hospital, brought some equipment and pharmaceuticals to the Rebbe’s room. The Rebbe’s heartbeat was noticeably abnormal, but he still refused to go to the hospital. At 5:30 AM, the doctors said that if the Rebbe refused to go to the hospital, they would leave, and they did.

The doors to 770 were locked to avoid noise, and no reports were given. Some people grouped in front of the building. Others went home for a disrupted seudas yom tov. At 5:30, the frum doctors who were at 770 conferred and concluded that they had no choice but to sedate the Rebbe, put him in an ambulance, and take him to a hospital. Suddenly, the Rebbetzin came down from the second floor and calmly asked, “What’s going on?” The doctors told her that the Rebbe was in mortal danger and needed serious medical care. They could not take responsibility for the Rebbe’s life, and insisted that he be taken to a hospital. But the Rebbetzin was the Rebbe’s next of kin; they couldn’t take him without her premission.

She declared, “All the years that I know my husband, I don’t recall a second when he was not in total control of himself.” She would not agree to take that away from him. The Rebbetzin reportedly also said that she never once did anything against his will. The Rebbetzin followed Rabbi Krinsky into the office. “Rabbi Krinsky,” she implored him, “you know so many people. Can’t you find a doctor for my husband?” As soon as she said that, Krinsky remembered a doctor from Chicago who was a cardiologist. The doctor had sent the Rebbe a book about arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat). Maybe he could come and help the Rebbe avoid hospitalization? When Rabbi Krinsky finally reached Dr. Ira Weiss, he said that if the Rebbe doesn’t want to go to the hospital, don’t take him! He explained that for a person with the Rebbe’s stature, doing something the Rebbe doesn’t want can be harmful. He flew out to New York immediately. A colleague of his, Dr. Teicholtz, from Harvard Medical, came with arranged police escort, and they brought the appropriate medicines. Both doctors agreed that it was very wise of the Rebbe not to go the hospital—taking him against his will could have been psychologically damaging. Dr. Ira Weiss stayed for two and a half weeks at the Rebbe’s bedside.

“Consider the Rebbetzin’s situation,” Rabbi Krinsky said. “Every doctor said that the Rebbe must be taken to the hospital. The Rebbe said no. She was the daas yechida (solitary voice); she supported the Rebbe’s wish. Her shikul hadaas (stance) was so correct, perfect, and accurate. This was probably the most critical juncture in the Rebbe’s life, physically speaking, and she made the determination. If the Rebbe had one Chassid in the world, it was her, in terms of her respect for his decision. She helped people understand the Rebbe’s words.”

The Rebbe was well enough to go home on Rosh Chodesh Kislev.

My children

Not much is publicly known about the Rebbetzin’s role in her husband’s work. Rabbi Krinsky said that she shared the Rebbe’s vision. The Rebbetzin was “absolutely” involved in the Rebbe’s work, Rabbi Krinsky said, “affecting events at every juncture.” She was always very aware of the latest campaigns, events, and activities in Lubavitch and around the world. She expressed profound gratitude for Chabad shluchim and admired them immensely, frequently referring to them as “young couples who moved far away from their families.” She often spoke about how difficult their lives are, how they have to have their meat flown out and bake their own bread.

Once, Mrs. Leah Kahan visited the Rebbetzin and noticed some crafted items out on the table. The Rebbetzin told her that they were a gift from shluchim and expressed amazement that the busy shluchim would remember her and send a gift. Mrs. Kahan somewhat exasperatedly responded that the Rebbetzin must be aware of what she means to the shluchim. The Rebbetzin looked at her and answered that Mrs. Kahan must be underestimating how busy the shluchim are.

Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka was also proud of her husband’s activities. She once asked Mrs. Louise Hager how children in London were responding to the Rebbe’s Tzivos Hashem program. “Of course, I was able to tell her of the great excitement,” related Mrs. Hager. “This huge smile came on her face, and she said, almost shyly, ‘My husband had a good idea, didn’t he?’” Recalling the many piles of newspapers, in multiple languages, around the house, Mrs. Hager said, “She was his researcher.”

A young child who once came to visit the Rebbetzin asked where her children were. The Rebbetzin responded that all the Chassidim were her children. And to anyone who knew her directly, the Rebbetzin was a concerned, solicitous, nurturing maternal figure. She prepared toys and snacks when she knew children were coming to visit. She was a gracious and kind listener. “You could talk to her about anything,” remembers Mrs. Kahan. Hadassah Carlebach said the same thing: “The Rebbetzin was a person that you felt comfortable telling her everything. She listened and showed concern, and asked me how things [were] going. [She] made me feel very good, and comforted me many times.” When Mrs. Hager’s mother was ill with cancer, the Rebbetzin provided a compassionate ear, and researched various treatments. A few hours before she passed away, while on her way to the hospital, the Rebbetzin asked her doctor about his newly engaged daughter and her chosson.

Indefatigable

One of the most popular stories about the Rebbetzin illustrates the theme of her entire life.

In the spring of 1985, it became noticeable that someone was taking books from the previous Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s, collection. The librarian noticed that the spaces between the books were becoming looser. When the Rebbe was told about it, he became very upset and spoke publicly about the issue. The Rebbe explained that the sefarim and manuscripts belonging to his father-in-law, the Sixth Rebbe, were an expression, almost an embodiment, of him, and to dismantle the library and sell it was an enormous spiritual blunder. Cameras were set up near the entrances. The person who had been secretly taking the books was discovered. He had taken over 400 of the best books and was selling them to book dealers. He sold one, an illuminated Haggadah that was a hundreds of years old, to a dealer for $69,000. The dealer turned it over to a collector in Europe who paid $150,000.

The person responsible refused to return the books. A restraining order was obtained to stop the book sales. After receiving a heter (special permission) from rabbanim, they went to court to decide to whom the library belonged. During the discovery phase of the trial, the opposing attorneys wanted to depose the Rebbetzin. While some were hesitant to allow the Rebbetzin to be deposed, the Rebbe assured that it would be fine—“she’ll come through with flying colors,” he said.

The deposition took place in her dining room. A court reporter recorded the proceedings, and Rabbi Krinsky and lawyers from both sides were present. The entire procedure took an hour and a half. The Rebbetzin was provided with a translator, even though she spoke in perfect English with impeccable diction. Rabbi Krinsky recalls that “The purpose is to confuse a person. The lawyers yell and raise their voices. It is very uncomfortable and accusatory. The Rebbetzin, a woman in her 80s, was on target, consistent, and did not get confused at all.”

Toward the end of the deposition, the lawyers were frustrated. One lawyer, hitting his pencil on the table, asked, “Didn’t the library belong to your father?” “My father owned nothing,” she responded. “My father belonged to [the] Chassidim, and everything he had belonged to [the] Chassidim”—then she turned to Rabbi Krinsky and audibly continued—“Only his tallis and tefillin belonged himself.”

The Rebbetzin’s testimony was very powerful and had a strong impact on the judge presiding over the trial. Chabad’s victory in this court case is often attributed to her.

Ultimately, Lubavitchers celebrate the Rebbetzin’s sacrifice, the way she shared her husband with the entire world. Even her wedding anniversary, a deeply personal milestone for most, was another connection between the Rebbe—and his Chassidim. N

To subscribe to Ami Magazine, call 718-534-8800 or email subscriptions@amimagazine.org. Mention Crownheights.info for a special subscription discount.

Empire Blvd

Nice job, Miriam! Go Yonit! And the whole Ami crew!

yid

thank you for putting this online i loved it!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

great job!

fantastic!

EXCELLENT READ

FABULOUS FABULOUS ARTICLE. THANK YOU SO FOR SHARING IT WITH ALL OF US! KEEP MORE COMING ON THE REBBETZINS OF LUBAVITCH.

sheva

well written, well researched. it was inspirational. thank you for sharing with “on line” readers.

lucky luba

did Ami actually had this picture of the Rebetzen in the magazine ?