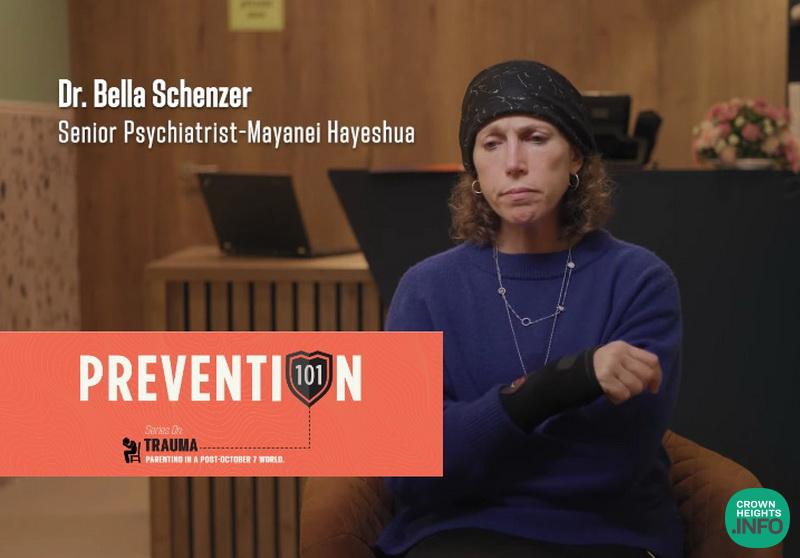

Prevention101: Series on Trauma: Episode #3 – Do People Respond Differently to the Same Traumatic Events? How do Children React to Trauma?

Series on Trauma: Episode 3 – Parenting in a Post-October 7th World. The series addresses questions regarding trauma following the massacre of October 7th and the surge of global anti-Semitism.

Do people respond differently to the same traumatic events? How do children, specifically, react to trauma?

Yes, people respond to the same trauma in different ways. We could have ten children in a room and we’ll have ten different experiences. It’s important to remember that my experience of trauma may be different from your experience of trauma even if we use the same definition.

In terms of how we respond, in the immediate sense, most people will have some response. Responses vary along a spectrum. There is the physical response. We’ll have an increased heart rate. We’ll feel chest tightness. Maybe we’ll sweat a little bit, or maybe we’ll feel nauseous. Our pupils might dilate. Many people will have a physical response even if they are not completely aware of it.

There is a more cognitive type of response as well. Inside our head, we’re trying to make sense of something that doesn’t seem to make sense because it is so beyond the pale of what we expect to experience as human beings. It is a kind of cognitive dissonance. We know this isn’t appropriate or something doesn’t make sense. Our brain doesn’t have a place to put this. It doesn’t fit in with our experience of the world.

Children can have that response too. For children, this is even harder because they don’t necessarily have the words to articulate that it doesn’t make sense to them.

The physical and cognitive responses often happen immediately, and in the first three months after the event, we can start seeing some other symptoms. The majority of individuals will just have that. While they are watching a video or being near a march or feeling threatened, they’ll have some of that acute response, but then as soon as they walk away, it’s done.

There is a smaller group who will have more complex symptoms for a short period of time. This would be considered an acute stress response. This is not just for children; this is for any age. In an acute stress response, there can be some avoidance, sleep disturbance, and some dissociative phenomena where they try to block out what they saw. We may see them spacing out or becoming a bit emotionally numb. They may also have flashbacks and re-experience the event.

This doesn’t mean the individuals in this smaller group who experience an acute stress response are going to go on to have long-term symptoms. For most individuals in this smaller group, their symptoms will completely resolve within three months. And for those people, support is all that is needed.

There’s a much smaller minority who will go on to develop post-traumatic stress disorder, which is a complex group of symptoms. These may include hypervigilance, where someone may be more on alert, or re-experiencing, where someone may have nightmares and flashbacks, or avoidance, where someone may try to minimize reminders of what happened. But this is a much smaller group.

Parents often wonder what they should look out for in their children after a traumatic event, but more importantly, they should speak to their children and ask them how they’re feeling. Make sure you’re talking to your children. Find out what they saw. Find out how they feel. Don’t assume that just because you are worried that your children are also worried. Don’t assume that because you’re not worried, your children are also not worried. When you’re not sure what exposure to trauma your child has had or how your child feels about the trauma, you must talk to them.

Asking your children how they’re feeling or asking them if they know what’s going on is not going to lead to them having ideas in their head. Let’s say you ask your children, “Are you scared?” If they are scared, they are going to think “Finally, my parents are giving me permission to tell them how scared I am.” If they are not scared, they’ll tell you, “No, I’m not scared.” Generally speaking, you’ll know if your child is being honest with you.

The key is to talk to your children. Communication between parent and child, between husband and wife, between friends, is the most important thing people can be doing right now to touch base and make sure that the person you are worried, concerned, or care about knows they can talk to you and knows they have a place to express themselves if they need to.

Unfortunately, as horrible as this is—because this was real—our children have been exposed to so much stuff that is not real that, to a degree, there’s been a little bit of numbing. This overload may have led to a degree of desensitization. Their brains have had to process an overwhelming amount of information. While this may have equipped them somewhat to cope with current challenges, it’s crucial to recognize that your child likely needs to communicate their feelings. Open and honest communication is paramount in times like these.

Bella Schanzer, MD, is a board-certified general adult psychiatrist with over two decades of experience providing evidence-based, holistic care to individuals grappling with mental health challenges.

Where can I find Parts 1 and 2?

Would like to read/hear the rest of this series.

Thanks