Weekly Dvar Torah: A Better Jew in America — Two Rebbes, Three Stories, One Fire

These days place us inside one of the most powerful and meaningful forty-eight-hour stretches on the Jewish calendar.

On Wednesday, Yud Shvat, we mark the 76th yahrzeit of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson, the Sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, and immediately afterward, on Yud Alef Shvat, the 75th anniversary of the moment his successor, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, accepted the leadership as the Seventh Rebbe.

Two Rebbes.

Two completely different worlds.

One mission that never wavered.

1929: Before America Was “Different”

Long before the Sixth Rebbe arrived in America for good, he visited the United States in 1929. While traveling through Philadelphia, he stayed in a hotel and received visitors throughout the day and late into the night — rabbis, community leaders, simple Jews, businessmen — all waiting patiently for a few minutes with a Rebbe from Europe.

The hallway was crowded. The mood was respectful. Quiet anticipation filled the air.

Off to the side stood two young Jewish businessmen. Well dressed. Confident. Financially successful. Thoroughly American. They watched the scene with curiosity mixed with skepticism.

“A rabbi from Europe?” one whispered with a half-smile.

“This whole thing is about money. They know who we are. Watch — we’ll be brought right in.”

When the secretary approached and asked why they wished to see the Rebbe, one of them answered impulsively — half joking, half testing the system:

“We want to ask him how to be better Jews in America.”

To their surprise, the secretary nodded and motioned them forward.

They were ushered in immediately.

The moment they crossed the threshold, their confidence dissolved.

The Rebbe sat quietly at the table. His face was gentle, but his eyes were penetrating — not judgmental, not harsh — simply seeing. The room felt still. The men suddenly realized they had no prepared question, no clever line, no practiced speech.

The Rebbe looked at them and smiled.

“I imagine you are wondering,” he said softly,

“why I allowed you to enter so quickly.”

They nodded, unable to speak.

“Many people come to me,” the Rebbe continued,

“for medical advice… business advice… legal advice.

Do you think I am a doctor? A businessman? A lawyer?”

Silence.

“When a Jew asks me for a blessing,” the Rebbe said,

“I bless him and pray to G-d.”

“But you asked how to be Jewish.”

“That,” the Rebbe said gently,

“is my field.”

When the Rebbe learned that they dealt in diamonds, he leaned forward slightly.

“Tell me,” he asked, “if you cannot sell a stone for the price you want, what do you do?”

“We lower the price,” they answered.

“And the next day?” the Rebbe asked.

“Do you permanently reduce the value of that stone?”

“Of course not,” they said.

“We reset the price and try again.”

The Rebbe smiled — a smile they would remember for the rest of their lives.

“That is how to be a Jew in America.”

“Every morning,” he said,

“you wake up at full value.

Some days, by nightfall, you may feel discounted.

You may fall short of your ideals.”

“But never redefine yourself downward.”

“The next morning, you begin again — at full price.”

Then, almost quietly, as if sharing a personal truth, the Rebbe added:

“I do the same.”

They entered the room as clever observers.

They left as Talmidim.

That message was not a slogan.

Ten years later, it became a lifeline.

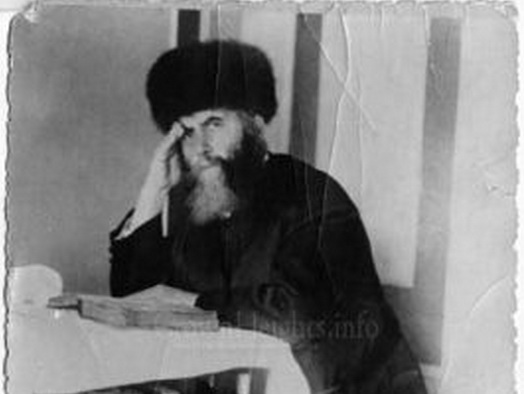

The Sixth Rebbe in the early part of the 20th century, led Lubavitch in a world where Judaism itself was illegal.

Under Stalin, teaching a child Alef-Beis was sabotage.

Keeping a mikvah was treason.

Running a cheder was a criminal conspiracy.

Chassidim lived with packed bags. Every knock on the door carried terror. Every lesson taught was an act of defiance.

The Soviet authorities tracked every Chassid connected to Rabbi Schneerson with chilling precision. Conversations were monitored, movements logged, and underground teachers were followed as if they were plotting the downfall of the regime. It was as if Stalin had invented Google, wiretaps, and smartphones decades early.

The Rebbe did not flinch.

Then came another miracle.

The Rebbe escaped Nazi Europe and arrived in the United States in 1940.

People expected relief. Adjustment. Rest.

Instead, the Rebbe declared:

“America is no different.”

Freedom is not safety.

Comfort is not continuity.

Assimilation can be more dangerous than oppression.

On his very first day, the Rebbe began opening schools.

History has spoken:

Every spark of Judaism that survived behind the Iron Curtain exists because of the Sixth Rebbe.

In 1971, a small group of Chabad Chassidim were finally allowed to leave the Soviet Union.

Among them was Reb Yankel Notik.

Rabbi Moshe Feinstein asked to meet them.

He himself had lived in Russia at the dawn of the Soviet era. He had fled when Yeshivos were shut, shuls destroyed, and Jewish life crushed.

When Reb Moshe heard Reb Yankel speak Torah — fluently, deeply, effortlessly — he leaned forward, visibly shaken.

“How did you do this?” Reb Moshe asked, his voice trembling.

“I was there. I saw it collapse.

No Yeshivos. No teachers. No books.”

“Keeping Shabbos was impossible.

Teaching children was suicide.”

Tears welled in Reb Moshe’s eyes.

“How do Jews come out of that country fifty years later — not barely able to read a siddur — but as giants in Torah?”

Reb Yankel shifted in his chair.

“What could we have done otherwise?” he said quietly.

Reb Moshe pressed him.

“I don’t understand,” he said.

“There was no infrastructure. No support. No future.”

Reb Yankel nodded.

“Yes,” he said.

“That’s true.”

Then he added — simply, without drama:

“If I wouldn’t learn Torah, I wouldn’t be a Jew.”

“So what choice did I have?”

No speeches.

No heroics.

Just one sentence — and an entire generation was explained.

Then came the Seventh Rebbe — in a world where Judaism was not beaten, but gently buried.

At his inaugural address, he warned:

“Do not think you have acquired a Rebbe and can now relax.”

“This is an army. Everyone must enlist.”

Years later, a Bar Mitzvah boy stood before him.

“Do you play baseball?” the Rebbe asked.

“Yes.”

“Do you watch the major leagues?”

“Of course.”

“Why?” the Rebbe smiled.

“You already play yourself.”

“When we play,” the boy answered honestly,

“it’s child’s play. Major league is real.”

The Rebbe leaned forward.

“In your heart, there is a playing field.”

“Two teams are battling — the spiritual and the material.”

“Until now,” the Rebbe said,

“it was child’s play.”

“From today on — the game is for real.”

“Play well,” he concluded,

“and the better side will win.”

Two Extremes. One Mission.

The Sixth Rebbe produced Jews like Reb Yankel Notik, who emerged from Soviet Russia as towering Torah scholars. When Reb Moshe Feinstein asked with tears in his eyes, how such spiritual greatness was possible under communism, Reb Yankel answered simply:

“What choice did we have?”

The Seventh Rebbe produced thousands of young couples who choose to leave comfort, family, kosher supermarkets, and thriving communities — to live in isolation, sometimes in trailers, just to help one Jew put on tefillin or light Shabbos candles once.

One Fire

One Rebbe taught Jews how to survive when Judaism was a crime.

One Rebbe taught Jews how to give everything away when comfort was the danger.

Two Rebbes.

Three stories.

One unbreakable fire.

Live Judaism not as child’s play,

but as major-league Avodas Hashem.

Have a Shabbos of Courage, Inspiration, and Holy Ambition,

Gut Shabbos

Rabbi Yosef Katzman