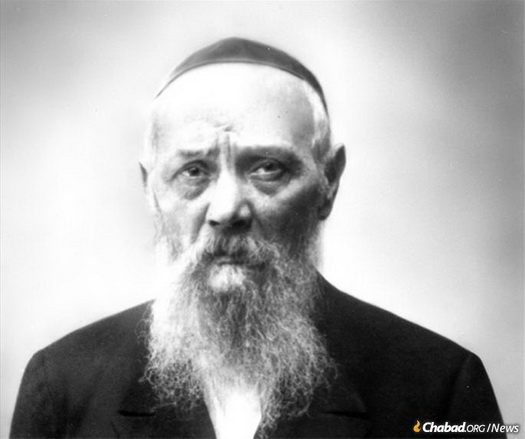

Weekly Dvar Torah: Eighty Years Since the Passing of Harav Levi Yitzchock Schneerson

On Shabbos, Chof Av (20th of Av) this year, 5784 (2024), we commemorate the 80th yahrzeit of Harav Levi Yitzchock Schneerson, affectionately known as Reb Levik, the father of the Lubavitcher Rebbe. His passing in Almaty, Kazakhstan, followed a grueling five-year period of imprisonment and exile under the Russian Communist regime. Reb Levik’s legacy is intertwined with the Rebbe’s, but his own profound contributions as a Torah scholar, Kabbalist, and leader of Soviet Jewry are significant in their own right.

Reb Levik was a distinguished leader, serving as the chief rabbi of Ekaterinoslav (now Dnieper), Ukraine. He was respected across various Jewish communities, including secular and communist Jews. He was once accused by secular Jews that he disrespected his position as Rabbi, because he danced with a simple Jew on Simchas Torah, this they argued is not appropriate for a great Rabbi, they felt humiliated because they could only attribute such behavior to someone who is drunk, and this was a crime in Soviet Russia.

Reb Levik was a strongly determined Rabbinical leader, who would not bend the Rules of Yiddishkeit. One notable episode of his defiance occurred when the Soviets pressured him to approve flour for Passover Matzos. Reb Levik would not give his stamp of approval unless the production of the flour met all Halachic requirements. Despite threats of arrest for potentially harming the USSR economy, he refused to budge, and in order to have things done the correct way, he traveled to Moscow to meet President Kalinin. The president ultimately decreed that Reb Levik’s rulings should be respected, highlighting his unwavering commitment to Halacha.

In 1939, Reb Levik was arrested on charges of counterrevolutionary activities. He was moved from prison to prison and ultimately exiled to Kazakhstan. His final years were marked by severe hardship until his passing on the 20th of Av, 1944.

Reb Levik’s commitment to Torah study endured even in exile. When his wife, Rebbetzin Chana, learned of his plight, she traveled across the USSR to be with him. On top of facing the severe lack of basic staples like food and shelter, realizing his pain of not being able to write his Torah, she foraged for grasses that could be used to produce ink, enabling Reb Levik to continue writing on the edges of few books that he had, which included a Tanya and a set of Zohar. These writings were later recovered and published by the Rebbe.

The risks taken by Chassidim to support Reb Levik were extraordinary. Any contact with Schneerson was a guaranteed sentence of 10 years in prison or the Gulag. My great uncle, R’ Yoske Nemotin, who was also exiled to Almaty, went to great lengths to help Reb Levik. He would prepare food and, to avoid detection, drop it off outside Reb Levik’s apartment with a loud bang on the door while running away quickly. Despite the peril, he maintained this dangerous routine to ensure that Reb Levik and later his widow, Rebbetzin Chana, received basic necessary provisions for survival.

Upon relocating to the United States in the early 1980s, my great uncle and his family were invited to a private audience with the Rebbe. During this meeting, the Rebbe expressed profound gratitude for the sacrifices they made on behalf of his parents. He emphasized that his indebtedness to my great uncle was because he performed a duty that he, the Rebbe, was obligated to honor his parents and was not able to. The Rebbe said that he had an obligation towards him which was beyond measure, and that he never wanted to be relieved of this obligation for compensation, a sentiment he publicly affirmed in a Farbrengen attended by thousands.

In reflecting on the 80th yahrzeit, it is noteworthy to examine Reb Levik’s interpretations of his suffering, particularly his connection to the concept of Gevura and the significance of the number eighty. Reb Levik himself elaborated on this in his writings, drawing from Kabbalistic teachings.

The Mishna states, “בן שמונים לגבורה” (“Eighty is strength”), which connects the number eighty to the attribute of Gevura, representing strength that also manifests as harshness. Reb Levik’s reflections align with this concept. He viewed his experiences through the lens of Gevura, connecting his trials to both strength and harshness. His arrest and imprisonment were not just arbitrary but had profound symbolic meanings.

Reb Levik’s name itself, Levi and Yitzchock, both represent Gevura in the teachings of Kabbala. And its numerical value further underscores this connection. His full name, “לוי יצחק בן זעלדא רחל,” has a numerical value of 656, which corresponds to the Hebrew word “שושן” (Shushan). Shushan, associated with the red rose, symbolizes strength and harshness in Kabbalistic thought. This connection is also evident in the date of his sentencing, which coincided with Hoshanah Rabbah—a day traditionally associated with efforts to sweeten harsh judgments.

Reb Levik’s imprisonment lasted for 303 days, a number corresponding to the Hebrew letters of “שבא” (Sheva), representing severity. Additionally, his five years in prison followed by exile can be associated with the five measures of harshness in Kabbalistic tradition. These numerical and symbolic associations reflect his deep understanding of his suffering as part of a divine plan for spiritual elevation and forgiveness.

Reb Levik’s life and teachings offer profound lessons on resilience and the search for meaning amidst adversity. His perseverance in the face of immense hardship and his contributions to Torah study serve as a powerful reminder of the strength of faith. On this 80th yahrzeit, let us engage with his teachings and reflect on the depth of his spiritual insights. His legacy encourages us to find purpose in our own challenges and strive towards spiritual growth.

Have a meaningful and reflective Shabbos,

Gut Shabbos

Rabbi Yosef Katzman