Weekly Dvar Torah: The ‘Wayward City’, ‘Condemned City’ and ‘Idolatrous City,’ ‘Ir Hanidachas’

In this week’s Parsha, we delve into the following teachings:

“Unfaithful individuals have emerged from within your midst and have led the inhabitants of their city astray, proclaiming, ‘Let us go and worship other deities, which have been previously unknown to you.’ “

The Torah instructs that if an entire city strays to the extent of embracing idol worship, that city transforms into an ‘Ir Hanidachas’, a condemned city, necessitating its obliteration. All residents must be put to death, and all possessions must be reduced to ashes.

Continuing, the Torah outlines the process:

First, an inquiry, investigation, and thorough examination must be conducted to confirm the veracity of the alleged abomination within the city.

A delegation of scholars is appointed to scrutinize the claim that the entire city has adopted idolatry.

The populace must be warned that persisting in their corrupt ways will lead to their demise.

Should they persist, the Sanhedrin convenes for another comprehensive investigation.

The verdict is then pronounced:

“The inhabitants of that city must be struck down by the edge of the sword, the city and all its possessions, including livestock, must be utterly destroyed.”

Upon conviction, the city is condemned, and the guilty inhabitants meet their fate by the sword.

Yet, the Torah extends beyond mere retribution:

“All spoils must be gathered into the city’s square and set ablaze, reducing the city and its spoils to an everlasting heap of destruction, never to be rebuilt.”

Notably, all possessions of the city and its inhabitants are to be assembled and incinerated, ensuring the city’s permanent demise.

Furthermore, the city is forbidden from reconstruction.

Essentially, the criteria for a wayward city’s condemnation to utter obliteration consist of several factors:

The entire population must participate in idol worship.

Every city possession must be collected and destroyed.

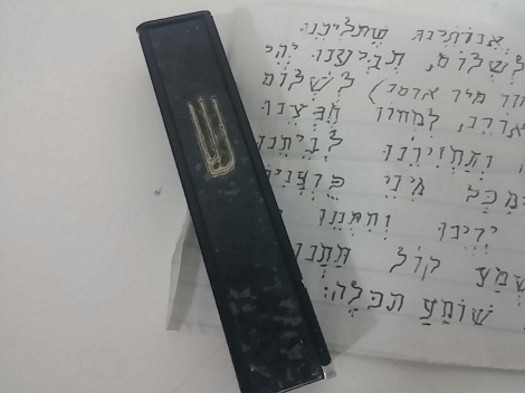

No holy scripture, not even a Mezuzah, can be present, as holy writings cannot be destroyed. Failure to incinerate all possessions nullifies the entire verdict.

It’s an all-or-nothing scenario.

The Talmud asserts that the concept of ‘Ir Hanidachas’ is theoretical and unattainable. Why? Because it’s highly improbable for an entire city to engage in idol worship. Also, gathering every item for burning is impractical. Discovering no holy scriptures in the entire city, not even a Mezuzah, is unrealistic. Essentially, ‘Ir Hanidachas’ is an unattainable ideal.

One might wonder why the Torah expounds on laws and details of an unfeasible scenario. The Torah, in fact, conveys a powerful message about being Jewish. Even when a Jew descends to the depths of idol worship, the lowest point imaginable, there’s still hope. The investigation reveals his true essence. Is he solely evil, or does he possess redeeming qualities?

The Torah emphasizes that finding just one Mezuzah within the city saves it from destruction. The Mezuzah, affixed to the entrance, represents a Jew’s core, proclaiming the unity of G-d. Despite surface missteps, the essence of a Jew remains connected to G-d through the Shma Yisrael.

Don’t judge a Jew by appearances; their inner essence remains tethered to G-d’s presence. This is what truly matters in the eyes of G-d.

To illustrate this message, let’s turn to a real-life story involving Shulamit Aloni, an Israeli left-wing, anti-religious member of the Knesset. On one occasion, she took the podium of the Knesset and delivered a fervent anti-religious speech, laced with fiery rhetoric against religion and religious Jews. Yet, after concluding her impassioned address, an unexpected scene unfolded. A Chabad Shliach, tasked with distributing Matza for Passover to all MPs, caught her attention. Approaching him, she inquired, “Berke, where are my Matzos?” A bystander couldn’t help but voice their astonishment, “You? After that scathing anti-religious speech, you now seek Matza from this religious individual?” Without hesitation, she responded, “Let it be, that was a matter of politics. But I require Matza for Passover!” This anecdote resonates deeply, echoing the core theme. Just as Shulamit Aloni’s pursuit of Matza defied her previous fiery stance, the Matza itself symbolizes the essence of a true Jew. The vehement anti-religious speech masks a deeper reality; it’s a mere political facade. In essence, it’s not the genuine Shulamit Aloni speaking in those moments.

This story echoes the essence of the lesson. Just as Shulamit Aloni’s core identity was displayed through her desire for Matza, the Mezuzah signifies the authentic essence of a Jew, irrespective of external appearances or past mistakes. The Mezuzah, like the Matza, symbolizes the enduring connection to one’s faith and heritage, even in the face of temporary veils that may cloud it.

Have a self-revealing G-dly Shabbos,

Gut Shabbos

Rabbi Yosef Katzman