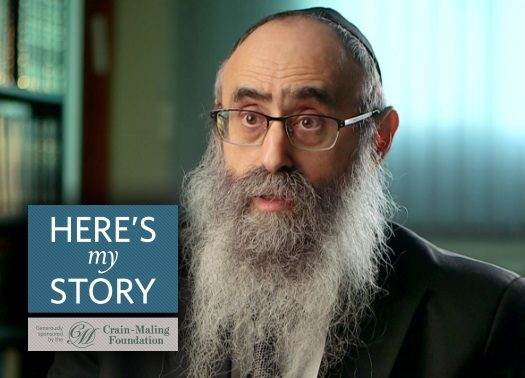

Here’s My Story: True Merits

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Gluckowsky is the Assistant Director of the Chabad Rabbinate in Israel and the director of the Chabad Rabbinate in Rechovot, where he has served as the Rebbe’s emissary for nearly 40 years. He was interviewed by JEM’s My Encounter with the Rebbe project in October of 2016.

Click here for a PDF version of this edition of Here’s My Story, or visit the My Encounter Blog.

In 1978, I was part of a group of Chabad students sent to bolster Torah learning in Israel. We came to Jerusalem and joined the studies at the Tzemach Tzedek synagogue in the Old City of Jerusalem.

While there, I remember the day when the Chabad emissaries came in saying that they received a message from the Rebbe to make sure that we, the young students, were “being prepared for leadership positions – to become rabbis, rabbinic judges, activists and administrators.”

When we heard that we started to laugh, because we were all in our early twenties, and we couldn’t imagine ever being leaders. But the Rebbe had a vision and he knew, much better than we did, what we were there for.

As it turned out, most of us remained in Israel. One by one, we married Israeli girls and became the Rebbe’s emissaries throughout the Land. I myself was offered a position as rabbi of the Chabad community in Rechovot. At the time, only eighteen Chabad families lived there, and I wrote to the Rebbe that this post appealed to me because Rechovot was a young community and I was a young man. I added, “I feel in my heart that this is the right fit for me.”

The Rebbe responded, circling the word “heart” in my letter and adding, “This is what you should do and may it be at an auspicious time.”

This is how I became the rabbi of Rechovot and saw the community grow from a mere eighteen families to more than six hundred. Today, I am director of the Chabad Rabbinate in Rechovot, and I remember the Rebbe’s blessing so many years ago, when I was just twenty-two years old and I laughed upon hearing that I was being prepared to be a Jewish leader. I couldn’t imagine such a thing. But the Rebbe did.

In 1988, after I was already established in Rechovot, my father fell ill. He was still living in Toronto, working as a teacher at the Eitz Chaim Day School, when he sensed something was not right. He took a pill that was prescribed for his heart condition, he finished his workday, and on his way home, he stopped off at the local hospital – just to be sure.

An examination showed an irregular heartbeat, and the hospital kept him overnight. But in the morning, his condition did not improve, so the doctors wouldn’t let him go home. In fact, they kept him for three weeks, and he was still not getting any better. That’s when I got a phone call from my brother, asking me to come to Toronto. As it happened, I was the only one of my siblings who could come – my brother was battling pneumonia at the time and could not fly, and both of my sisters were pregnant and could not fly, so it was up to me.

I told my brother that I would clear my schedule and buy a plane ticket. Meanwhile, I asked him to be in touch with the Rebbe’s office and request a blessing.

A few hours later, my brother called me back. He said, “Don’t buy a ticket. We have an answer from the Rebbe.”

The Rebbe wrote: “From among all of the children, you want the one who has to leave the Holy Land to come? You want that one to stop all of his activities of spreading Yiddishkeit and the other things? And you think this will merit a long life for your father?”

It was clear to us all that the Rebbe didn’t think I should come. But my brother asked me, “What does he mean by ‘the other things’?” (Incidentally, this phrase was underlined twice).

I had to think about it, but then I realized that “the other things” might refer to two projects that I had been meaning to undertake but didn’t because I felt they might be too much for me. Right then and there, I decided to go forward in the merit of my father of recovering and living longer. And that’s what I told to my brother.

Over that weekend, my father improved dramatically and, on Monday, he was released from the hospital.

Here’s what I took away from this incident. One would think that, as a son, I should come to sit by the bedside of my father, make him a cup of tea, and share words of encouragement and inspiration. But the Rebbe felt that, if I increased my activities in the Land of Israel, that would help to improve my father’s welfare more than any personal visit ever could.

And speaking of my activities, I would like to describe one other incident which took place a year earlier.

In 1987, I came to New York for the holiday of Shavuot. At the end of the farbrengen, it was the Rebbe’s custom to distribute wine following the Havdalah ceremony that ended the holiday. After I received some wine in my cup, the Rebbe called me back and, with a broad smile on his face, handed me a little bottle of vodka and said: “This is for the Arabs.”

Puzzled, I looked at Rabbi Groner, the Rebbe’s secretary, as if to say “Did I hear that right?” But Rabbi Groner said nothing, and the Rebbe just continued smiling.

When I returned to Israel, I learned that my colleague, Rabbi Yossi Gerlitzky, the Chabad emissary in Tel Aviv, was in the midst of a secret project of spreading the Sheva Mitzvot Bnei Noach – the Seven Noahide Laws. These seven commandments, by which all of humanity must live, were given at Mount Sinai; they prohibit blasphemy, idolatry, murder, theft, adultery, cruelty to animals and mandate the establishment of courts of law. On the Rebbe’s directive, Rabbi Gerlitzky had them translated into Arabic and, with the permission of the head of Arab education, was distributing them to fourth and fifth graders in the Arabic schools. I also learned that the Rebbe wanted me to get involved.

I offered to help Rabbi Gerlitzky in this effort and was invited to a meeting with the Arab educators participating in this project. I could see that they were very impressed that the Rebbe took such an interest in their children.

Subsequently the project expanded, and I was involved in distributing literature to an Arabic school in Be’er Sheva and, eventually, all over Israel. We were on the brink of also going to Gaza and the West Bank when the intifada broke out and it was cancelled.

The Rebbe pushed this project very much. It was important to him that all children should be educated about these basic commandments for all humankind. And, even if part of the project was cancelled due to war, I believe the very fact that it existed is a great example of the Rebbe’s vision and leadership.

Milhouse

But what was he supposed to do with the mashke for the arabs? It’s like the old joke about the servant in a Jewish home, explaining the Jewish holidays to her friend: Shabbos is when they eat in the living room and smoke in the bathroom, Tishabov is when they smoke in the living room and eat in the bathroom, and Yom Kippur is when they eat and smoke in the bathroom. So did the Rebbe want his mashke to be drunk in the bathroom?