Here’s My Story: 200 Years of Hindsight

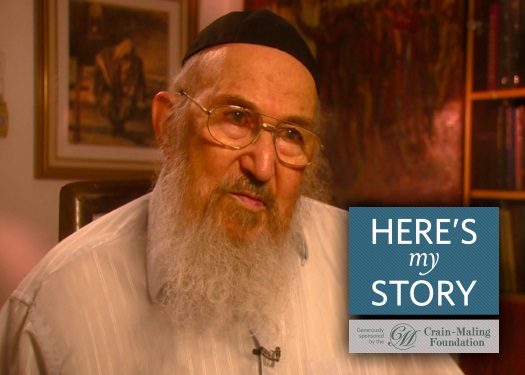

Rabbi Rafael Zamir was an educator for many years and resides in Tel Aviv, Israel. He was interviewed by JEM’s My Encounter with the Rebbe project in his home in August of 2010.

Click here for a PDF version of this edition of Here’s My Story. Click here to visit the My Encounter Blog.

I grew up in a non-chasidic background and interestingly enough, I married a girl from a Lubavitcher family. From the beginning, she asked me to accept Chabad customs and the Rebbe’s directives upon myself. For a while I resisted – I would keep my own customs while she kept hers. For instance, on Passover, she would eat hand-made matzah while I ate mine machine-made; she would keep her matzah dry, while I would dip mine in liquid.

Then, one day I decided to consult a rabbi – not chasidic – who actually told me that I should listen to my wife. As a result of his advice, I began conducting myself according to Chabad customs, except that I would not pray with the Chabad liturgy. The 18th century founder of the Chabad Movement, the Alter Rebbe, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, published a prayer book based on the Sephardic text used by the Ari, the great 16th century Kabbalist.

My wife suggested that I ask the Rebbe about this. I agreed and, in 1962, wrote him a letter: First, I asked, was it permissible for chasidim to change their prayer liturgy – wasn’t one obligated to follow familial custom? Second, how was it possible to know who was greater – the great chasidic master, the Alter Rebbe, or the great opponent of chasidic ways, the Vilna Gaon? Underlying my question was the thought that if such a great Torah scholar as the Vilna Goan was opposed to Chasidut, then why should I delve into its teachings?

I never received an answer to my letter, but about eight months later, I met the Rebbe in person for the first time. During our visit to New York, my wife and I were able to have two private audiences with him – one long meeting upon our arrival and a second, shorter, audience just before we left.

As our first audience was coming to an end, as we were turning to leave, the Rebbe stopped us, “One moment. I still owe you a reply to your letter.”

I stopped, surprised that, so many months later, the Rebbe still remembered it.

“Regarding your first question,” the Rebbe began. “If people had never varied from familial ways, the Chasidic Movement would never have been founded. However, Chasidism was not meant to nullify or change anything; rather its founder’s purpose was only to reveal new dimensions in Judaism that weren’t well known in those days.

“As for your second question, the Vilna Gaon’s opposition to Chasidism was based on the fact that it was an anomaly to him, and he was worried that it would lead to a deterioration of Torah observance. But now – over two hundred years later – you can see for yourself that this has not been the case. If I would ask you ‘How does a chasid look?’ You would describe to me a Jew who sports a beard, prays at length and fulfills mitzvot scrupulously. Had the Vilna Gaon foreseen how the Chasidic Movement would develop, he would certainly never have opposed it in the first place.”

But the Rebbe did not leave it at that; he continued: “In the yeshivahs of the Vilna Gaon’s era, they studied neither the ethical teachings of Mussar nor Chasidut, only Talmud. But, over time, religious Jews saw that the generations were growing weaker in Torah observance, and that in order to strengthen themselves, they had to broaden the subjects of study. Thus began the study of Chasidut in chasidic schools and Mussar in non-chasidic schools.

“Has anyone ever refrained from using a certain medicine by arguing, ‘My parents never took this medicine, so neither will I’? Perhaps the parents didn’t take this medicine because they didn’t need it; they didn’t suffer from that illness. But the son, who is unwell, needs to take the medicine.”

“But is changing the prayer liturgy considered taking medicine?” I countered.

The Rebbe responded: “The Alter Rebbe’s liturgy is based on chasidic teachings, so it is ideal, but you are not obligated to do so. However, you cannot dismiss the study of Chasidut – this is an obligation. In order to properly fulfill the biblical command to love and fear G-d, one must study Chasidut.”

That concluded our first audience. At the second audience, my wife complained to the Rebbe that I had not yet changed to the Chabad liturgy. The Rebbe replied, “Do not pressure him. Such a change can only come from within.”

“But I was hoping that you would convince him,” my wife persisted.

“No,” the Rebbe responded. “I will not pressure him either – it must come from within.”

Eventually, it did. After a time, I ended up changing over to the Chabad prayer book and becoming a devoted chasid of the Rebbe, whose loving care for every Jew became a constant source of inspiration to me.