Here’s My Story: Someone Is Praying for You

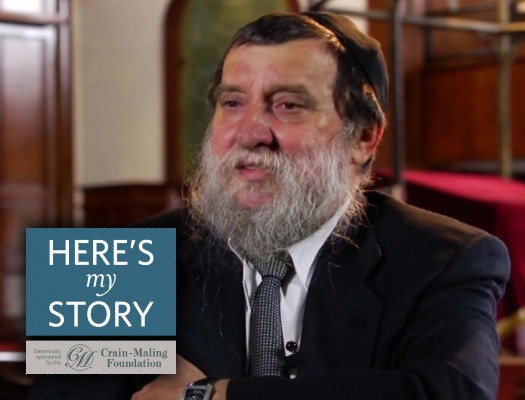

Rabbi David Golowinski is an authority in the field of Kosher supervision. He was interviewed by JEM’s My Encounter with the Rebbe project in Bal Harbour, Florida in April of 2011.

Click here for a PDF version of this edition of Here’s My Story, or here to visit the My Encounter blog.

In the summer of 1968, while I was studying at the Lubavitcher Yeshiva in Montreal, a fellow student and close friend of mine was appointed to be a teacher in the Lubavitch School in Boston, Massachusetts. In order to make the move, he asked me for my assistance. More than eager to help my friend, I agreed. We packed his family into the car and made the five-hour drive from Montreal to Boston. But, for me, the trip didn’t end there, as I needed to return to Montreal. Shortly after I returned to Montreal, I travelled to Chicago make to participate in a friend’s wedding. Upon my return to Montreal I decided to make the six-hour trek to Upstate New York to visit my younger brother who was working at a summer camp there.

I arrived late at night, and having driven close to 2,500 miles in a few days’ time, I was beyond exhausted. Too tired to look for my brother, I found his room and just collapsed on his bed. When he finally returned having no idea that I was there, he flipped on the light and woke me up. But when I opened my eyes, the indescribable happened – I felt as if a knife had sliced through my eyes; the pain was excruciating. I tried to go back to sleep but, of course, this was impossible and, as soon as morning arrived, I ran to the store to buy some Visine eye drops. They didn’t help at all. So, in great pain and having no choice, I got back home to Newark, New Jersey, where my mother arranged an appointment for me with an optician.

After examining my eye, the optician said, “I am sorry, but this is out of my league. I am going to refer you to an eye doctor by the name of Dr. Plain.”

Dr. Plain happened to be a Jewish doctor, although he struck me as someone who was uninformed of anything Jewish. He looked at my eye, spent several minutes examining it and then broke the news to me as gently as he could: “As a result of sleep deprivation, the pressure built up in your eye, and the cornea – tissue covering the eye – ruptured. Unless we perform a cornea transplant, you will lose your eye.”

In the meantime, he put a pressure patch on my eye to reduce the swelling and ease the pain. And he immediately arranged an appointment for me with a premiere eye surgeon in New York.

At that time there were only two doctors in America who performed such operations – a doctor in Texas and Dr. Kostoviaro in Manhattan – so Dr. Plain had to use all of his influence to squeeze me ahead of some two hundred people on the waiting list. However, he succeeded, and I was examined by Dr. Kostoviaro and his assistants. They concluded that surgery was necessary but, I would have to wait some time for a donor to become available.

Of course, I informed the Rebbe about the situation, who replied that I should first ask a Rabbi if it permissible to accept organ donations from a caveat as that may be considered disrespectful to body of the departed soul. I turned to Rabbi Yitzchak Hendel from Montreal who showed me an essay written by the Chief Rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Yehuda Unterman, which stated that in emergency situations, it would be permitted.

About three months later, I received a call that I should come in the next day – a Saturday – for the operation. I wasn’t going to hear of it; there was no way that I would desecrate Shabbat. As a result, Dr. Kostoviaro postponed my surgery until another donor would become available.

Meanwhile, I had a private audience with the Rebbe in honor of my birthday and I brought up my upcoming surgery.

The Rebbe said, “I know this Dr. Kostoviaro … But about the surgery, since it is highly technical and still in its primitive stages, I think it would be better to wait a bit longer until they have a chance to improve the procedure.”

I was more than happy to hear this, and I informed Dr. Kostoviaro’s office of my decision to postpone the surgery indefinitely. His people were furious and threatened to cut off all treatment.

When I went to Dr. Plain afterwards, he was also livid. “You must have this operation, or you could lose your eye!” he yelled at me.

Although I was relying on the Rebbe’s advice I did not explain this to Dr. Plain. I was sure that, not being Torah observant, he would never understand.

Time passed. One day, I came to Dr. Plain for a routine examination, bracing myself for another lambasting from him for not having the operation. But, instead, after he examined my eye, he said, “Someone must have been praying for you … Who was it? Rabbi Schneerson?”

I was stunned to hear him say that, so I just nodded my head. To this day it is beyond me to figure out how someone who seemed so detached from observant Judaism could arrive at that conclusion.

As it turned out, after all that time wearing the pressure patch, somehow the eye had healed itself and only a scar remained..

For several months I did have to wear the pressure bandage, but I never had to risk a dangerous operation.

Today, corneal transplants are done all over the world and the techniques involved were greatly enhanced. But back then, when this kind of surgery was in its primitive stages and only two doctors were performing it, I was lucky to be spared.

I shouldn’t say lucky, because – as Dr. Plain guessed – someone was praying for me.