Rebbe’s Letter from 1944 Explains Significance of Tu B’Shvat

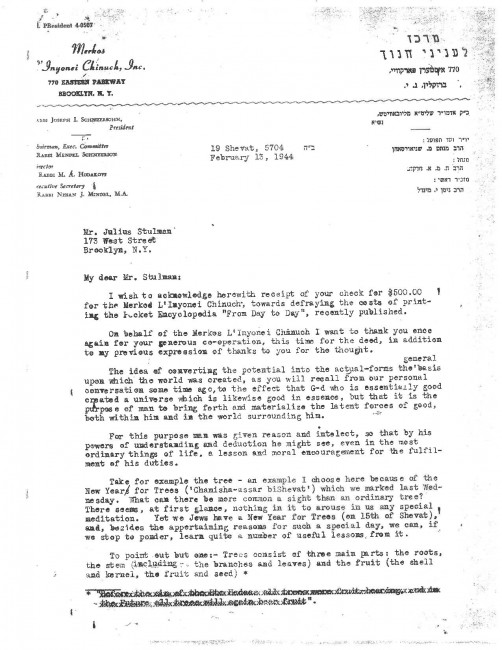

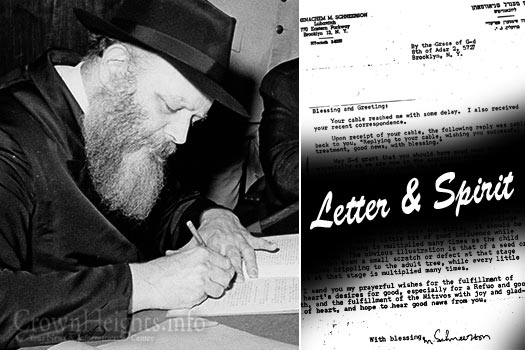

In honor of Tu B’Shvat, we present a letter from the Rebbe in 1944, when he served as Chairman of the Executive Committee of Merkos, written to a well-known supporter of the Frierdker Rebbe and Chabad in the early years in America.

The Rebbe thanks Julius S. for his generous support and the check he gave Merkos – which is being used for the publication of From Day To Day (the children’s Hayom Yom in English, which the Rebbe compiled especially for children in the years 1943 and 1944 – even before he did the Hayom Yom for the adults).

The Rebbe then goes on to expound on the significance of Tu B’Shevat.

This letter is from the forthcoming book Chabad in America through the Folders of Nissan Mindel by Nissan Mindel Publications (NMP).

*********

B’H

19th Shevat, 5704

February 13, 1944

Mr. Julius Stulman

173 West St.

Brooklyn, N.Y.

My Dear Mr. Stulman:

I wish to acknowledge herewith receipt of your check for $500 for the Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch towards defraying the costs of printing the Pocket Encyclopedia “From Day to Day”, recently published.

On behalf of Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch I want to thank you once again for your generous co-operation, this time for the deed, in addition to my previous expression of thanks to you for the thought.

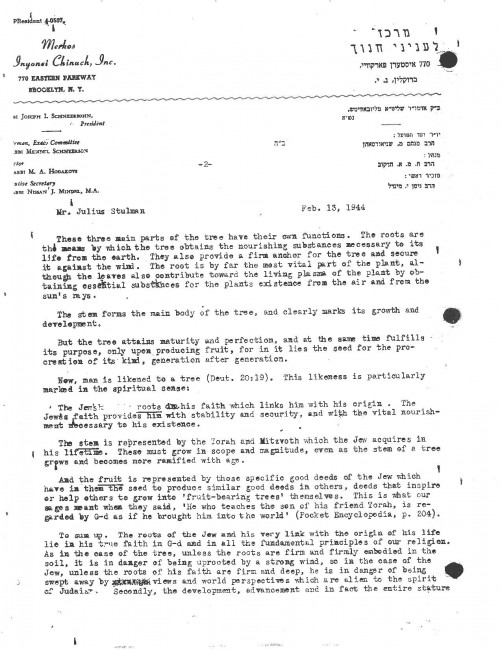

The idea of converting the potential into the actual, forms the general basis upon which the world was created, as you will recall from our personal conversation some time ago, to the effect that G-d Who is essentially good, created a universe which is likewise good in essence, but that it is the purpose of man to bring forth and materialize the latent forces of good, both within him and in the world surrounding him.

For this purpose man was given reason and intellect, so that by his powers of understanding and deduction he might see, even in the most ordinary things of life, a lesson and moral encouragement for the fulfillment of his duties.

Take for example the tree – an example I choose here because of the New Year for Trees (Chamisha Assar bi’Shevat), which we marked last Wednesday. What can there be more common a sight than an ordinary tree? There seems at first glance nothing in it ot arouse in us any special meditation. Yet we Jews have a New Year for Trees (the 15th of Shevat), and, besides the appertaining reasons for such a special day, we can, if we stop to ponder, learn quite a number of useful lessons from it.

To point out but one: Trees consist of three main parts: the roots, the stem (including the branches and leaves) and the fruit (the shell and kernel, the fruit and seed).

These three main parts of the tree have their own functions. The roots are the means by which the tree obtains the nourishing substances necessary to its life form the earth. They also provide a firm anchor for the tree and secure it against the wind. The root is by far the most vital part fo the plant, although the leaves also contribute toward the living plasma of the plant by obtaining essential substances for the plant’s existence from the air and from the sun’s rays.

The stem forms the main body of the tree and clearly marks its growth and development.

But the tree attains maturity and perfection and at the same time fulfills its purpose, only upon producing fruit, for in it lies the seed for procreation of its kind, generation after generation.

Now, man is likened to a tree (Deut. 20:19). This likeness is particularly marked in the spiritual sense:

The Jew’s roots are his faith which links him with his origin. The Jew’s faith provides him with stability and security and with vital nourishment necessary to his existence.

The stem is represented by the Torah and mitzvoth which the Jew acquires in his lifetime. These must grow in scope and magnitude, even as the stem of the tree grows and becomes more ramified with age.

And the fruit is represented by those specific good deeds of the Jew which have in them the seed to produce similar good deeds in others, deeds that inspire or help others to grow into “fruit bearing trees” themselves. This is what our Sages meant when they said “He who teaches the son of his friend Torah, is regarded by G-d as if he brought him into the world” (Pocket Encyclopedia, p. 204).

To sum up. The roots of the Jew and his very link with the origin of his life lie in his true faith in G-d and in all the fundamental principles of our religion. As in the case of the tree, unless the roots are firm and firmly embedded in the soil, it is in danger of being uprooted by a strong wind, so in the case of the Jews, unless the roots of his faith are firm and deep, he is in danger of being swept away by views and world perspectives which are alien to the spirit of Judaism. Secondly, the development, advancement and in fact the entire stature of the Jew are reflected in his good deeds, in the practice to the Torah and mitzvoth. Finally, his perfection is attained by producing “fruit” “whose seed is in itself” – by inspiring and benefiting others and thus helping to perpetuate our great heritage of Mt. Sinai.

In the light of the above, the saying of our Sages which I quoted in my last letter to you, that “He who benefits the many, the virtue of the many is credited to him”, assumes proper meaning and significance, for this truly is the highest form of virtue.

With kindest personal regards,

Very sincerely yours,

(Signature)

Rabbi Mendel Schneerson,

Chairman, Executive Committee

RMS:NM