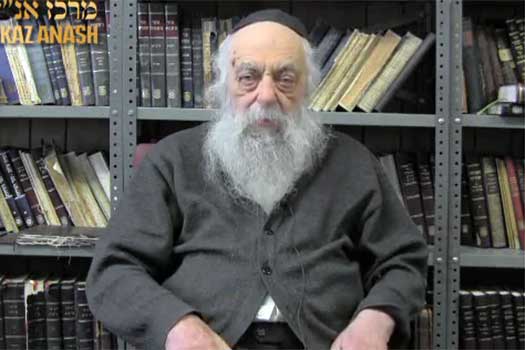

Reb Yoel Kahn: Restraining the Love

Due to the overwhelming response and demand from the community, Reb Yoel Kahn agreed to present a weekly webcast on topics that are timely and relevant. This week’s topic is titled ‘Restraining the Love‘.

Reb Yoel Kahn, known to his thousands of students as “Reb Yoel,” serves as the head mashpia at the Central Tomchei Temimim Yeshivah in 770. For over forty years he served as the chief ‘chozer’ (transcriber) of all the Rebbe’s sichos and ma’amorim. He is also the editor-in-chief of Sefer HoErchim Chabad, an encyclopedia of Chabad Chassidus.

In response to the growing thirst of Anash for Chassidus guidance in day-to-day life, Reb Yoel has agreed to the request of Merkaz Anash to begin a series of short video talks on Yomei d’Pagra and special topics.

The video was facilitated by Beis Hamedrash L’shluchim, a branch of Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch

Parshas Acharei tells us of how “Hashem spoke to Moshe after the death of the two sons of Aharon”, with the instruction that Aharon “should not enter the kodesh ha’kadashim at all times”.

Rashi writes the following: Why mention the death of Aharon’s two sons? R. Elazer ben Azaryah would give a parable of a doctor who visited a patient and told him ‘don’t eat cold food and don’t sleep in damp places’; then another doctor came and said ‘don’t eat cold food and don’t sleep in damp places or else you’ll die just like so-and-so. Whose words were a greater deterrent? Those of the second doctor. That’s the reason that the pasuk says ‘after the death of the two sons of Aharon,’ so that Aharon would receive the most effective warning possible.

There are a number of questions on Rashi’s commentary here. Firstly, a parable is only necessary when something isn’t easy to comprehend; but what was so difficult about the concept of adding an example to a plain warning that a parable was necessary? Moreover, why the comparison to an ill person? If a healthy individual wished to do something dangerous, then certainly mentioning past victims would have a greater effect than just a plain warning; this would seem more appropriate here since Aharon was ‘healthy’, and only committing this forbidden act would put him in danger, and so why compare him to a sick man instead of a healthy one? And why the reference to cold food and damp places? Why those two out of all the possible harmful examples?

Sick with Love

The Rebbe explains that Rashi was actually bothered by a different, simple question. Didn’t Aharon always obey Hashem’s instructions? Nowhere else were examples of victims used in giving directions to Aharon! In fact, kohanim are prohibited to drink wine or alcohol when involved with the mikdash, and there’s an opinion which states that Nadav and Avihu had died because they had entered while drunk, and so this example could have been used in presenting the prohibition against drinking alcohol! Why then is the example of their death only used here, when doing so wasn’t necessary for the prohibition against alcohol?

To answer this question, Rashi presents the parable of an ill man. People who are sick typically have fever, a body temperature warmer than normal. The pasuk tells us that people who are ill “are disgusted by food,” and the Gemara states that they are “fed by the fever.” Due to the strength of the heat, sick people are attracted to the cold, and so when a doctor arrives and declares that cold things are dangerous, an ordinarily obedient patient might, in his great desire to alleviate the heat, ignore the doctor’s warning. Hence, in the parable, cautionary tales of previous victims are necessary.

Likewise, Aharon in fact was sick. He was “sick in love”, drawn to Hashem. And after the seven days of milu’im, the special rituals involving the mishkan, all he wanted was to experience more Elokus. Where would he be able to find that? In the kodesh ha’kadashim. Now while Aharon was unquestionably G-d-fearing, and obeyed everything, there was the possibility in this instance that being “sick in love”, he wouldn’t restrain himself, and he might die just as his sons did, which the Ohr Ha’chayim explains was due to k’los ha’nefesh, since he ‘suffered’ from the same ‘sickness’ they did. Addressing this, Rashi offers a parable specifically of someone who would ordinarily heed doctor’s orders, but due to his illness might be disinclined to listen.

Following Instructions

The two examples of cold food and damp places correspond to the two details in the command to Aharon: Never to enter the kodesh ha’kadashim, except on Yom Kippur with thekorbanos; those same korbanos should not be brought in an attempt to enter throughout the year, and when entering on Yom Kippur, it must be specifically with those korbanos. Thus there are two warnings: not to enter with the korbanos at the wrong time, and not to enter on Yom Kippur without the korbanos.

These correspond to eating cold food and sleeping in a damp place, respectively. Between the two, there’s a greater thirst for cold food, since it enters the body, providing greater relief, and therefore needs a starker warning, since it also presents a greater danger. Similarly,korbanos are “lachmi“, bread both for Hashem and the kohanim which offer it, and its effect is b’pnimiyus, in a more internal way. Whereas entering the kodesh ha’kadashim withoutkorbanos would be the equivalent of the Chasidic term ohr makif; the desire isn’t as great, since the effect is weaker, and similarly the attendant danger. And so Aharon was first warned not to enter all the time, even with korbanos, ‘eating cold food’, and then he was instructed to be sure to bring korbanos when he does in fact enter, [avoiding being in a ‘damp place’].

This is one of the reasons that this parsha is read on Yom Kippur, as it is an indication of the level we should strive to attain on that day. We should aspire to be connected with Hashem to the extent that we must be warned to avoid k’los ha’nefesh.

Incredible!

Wow! This is so timely and relevant! I often find myself struggling with my klois hanefesh issues. I find it relieving to finally hear someone say it like it is!

Kudos

is a yid

the link is missing please re post

Wow

Amazing, very good