Is “Turning the Other Cheek” Jewish? Judging Actions Not Motives

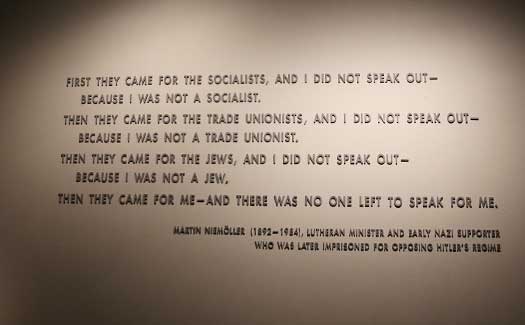

“THEY CAME FIRST for the Communists, and I didn’t speak up because I wasn’t a Communist.

THEN THEY CAME for the Jews, and I didn’t speak up because I wasn’t a Jew.

THEN THEY CAME for the trade unionists, and I didn’t speak up because I wasn’t a trade unionist.

THEN THEY CAME for the Catholics, and I didn’t speak up because I was a Protestant.

THEN THEY CAME for me and by that time no one was left to speak up.” (Pastor Martin Niemöller (1892–1984))

*********************************

It is the custom at our Shul to read a short meditation each morning upon the conclusion of services. It was the following thought in the name of the holy Baal Shem Tov that elicited a fervent debate:

“Your fellow is your mirror. If your own face is clean, so will be the image you perceive. But should you look upon your fellow and see a blemish, it is your own imperfection that you are encountering – you are being shown what it is that you must correct within yourself.”

“Does this mean that we can never perceive evil or wrongdoing without implicating ourselves,” protested a thoughtful and generally soft-spoken congregant. “I find this disconcerting!”

“What about Hitler, Stalin, Pol Pot, Hirohito of Japan or for that matter Osama Binladin, Achmadinidjad and their ilk? Is the recognition of their brutal and inhumane conduct reflective of one’s own evil propensities? With all due respect, this makes no sense.”

It was only a matter of moments before the entire room erupted in passionate debate. In proverbial Jewish tradition, voices came from all directions, weaving in and out of each other. “What do you think, Rabbi,” came a voice from across the room.

To be honest, I was caught off guard. The man clearly had a valid point. I myself am wont to preach against passivism and the popular ideology of moral relativism – the lack of absolute right and wrong.

My mind filled with thoughts of Biblical figures who seemed, at one time or another, to be judgmental. For example, did not Avraham judge Lot when he insisted that their camps separate as a result of Lot and his shepherds’ inappropriate conduct? Did not Yitzchak rebuke King Avimelach? Did Yaakov not complain bitterly about his uncle Lavan?

What about the many times that Moshe castigated the Israelites for the numerous rebellions against G-d? Did he not pray for the demise of Korach and company? Then there is Pinchas, the archetype of vigilantism who was highly rewarded for his quick judgment and zealotry.

The more thought I gave it, the greater the paradox seemed to become. The Torah’s position on judgmentalism seems at best confusing, if not outright contradictory.

In Ethics of The Fathers, for example, it is stated in one place: “Do not judge your friend until you have reached his place” – been in his shoes. Yet in another place it says: “Distance yourself from a bad neighbor and do not befriend the wicked.” How can there be a bad neighbor or a wicked-one if we’re not supposed to judge?

Seeing no way out, I acknowledged that the man’s point could not be ignored. To those who argued that the Baal Shem Tov said otherwise, I replied, “You’re right.” When others questioned how both can be right, I exclaimed in good rabbinic tradition, “You too are right!”

The issue could obviously not be resolved on one foot. But nor could it be ignored forever. No part of Torah can be left to contradiction, especially an issue as fundamental as the topic at hand – a matter with very practical day-to-day implications. Indeed, knowing when to judge favorably, when to be critical and when not to judge at all is an ongoing struggle in the life of every conscientious human being.

Before I had a chance to revisit the subject, I received an email from the same congregant. The email included the following essay (adapted) by a Psychiatrist named Dr. Emanual Tanay, of Ann Arbor, MI. Dr. Tanay bases his essay on the words of a man who was of German aristocracy prior to World War II – a man whose family owned a number of large industries and estates:

“Very few people were true Nazis, but many enjoyed the return of German pride, and many more were too busy to care. I was one of those who just thought the Nazis were a bunch of fools. So, the majority just sat back and let it all happen. Then before we knew it they owned us, we had lost control and the end of the world had come. My family lost everything. I ended up in a concentration camp, and the Allies destroyed my factories. . .”

“The hard quantifiable fact is that the ‘peaceful majority;’ the ‘silent majority,’ is cowed and extraneous. Communist Russia was comprised of Russians who just wanted to live in peace, yet the Russian Communists were responsible for the murder of about 20 million people. The peaceful majority were irrelevant. China’s huge population was peaceful as well, but Chinese Communists managed to kill a staggering 70 million people.

The average Japanese individual prior to World War ll was not a warmongering sadist. Yet, Japan slaughtered its way across South East Asia in an orgy of killing that included the systematic murder of 12 million Chinese civilians; most killed by sword, shovel and bayonet. And, who can forget Rwanda, which collapsed into butchery. Could it not be said that the majority of Rwandans were ‘peace loving’?

History lessons are often incredibly simple and blunt, yet for all our powers of reason we often miss the most basic and uncomplicated of points:

…Peace-loving Germans, Japanese, Chinese, Russians, Rwandans, Serbs, Afghanis, Iraqis, Palestinians, Somalis, Nigerians, Algerians, and many others have died because the peaceful majority did not speak up until it was too late…”

So, I ask you Rabbi, concludes the congregant, how do you reconcile the flowery notion of non-judgmentalism with the above stated facts? True, these horrific examples were all national tragedies – resulting from national apathy and gullibility – still, how different is it on the interpersonal level?

I’ve wrestled with this conundrum for quite some time. An answer has only come to me upon reading the commentary on this week’s Parsha.

In prescribing the remedy for Tzara’as – a leprosy-like malady brought-on by spiritual deficiency – the Torah states: The Kohen shall command and for the person being purified there shall be taken a stick of cedar wood, tongue-like strip of wool dyed crimson, and Hyssop (Vayikra 14: 4).

In explaining the significance of these particular objects Rashi states: “Because lesions of Tzara’as manifest itself as a result of haughtiness – symbolized by the tall cedar – he must, as a healing remedy, humble himself from his haughtiness through Tola’as (lit., ‘a worm,’ which infested the berries from which the crimson dye was extracted to color the wool) as well as the lowly hyssop.

According to Rashi, the cedar wood symbolizes the state in which the Leper found himself before the infliction – haughtiness, while the other two objects represent the cure – humility.

Other commentaries find this view somewhat inconsistent. Since the three objects are mentioned together, they ought to all represent the same existential state, either of the malady – haughtiness, or the state of cure – humility. It seems furthermore illogical that the healing Mitzorah would be instructed to take an object symbolizing the complete opposite state of where he is meant to be heading.

An alternative interpretation is hence presented, which in fact defines the symbolism of the cedar as part of the curing formula. According to this explanation, the cedar signifies the sense of determination and steadfastness that one must develop on behalf of morality, justice and Divine will.

In other words, the Leper most not come away from his traumatic misfortune with the wrong lesson by swinging towards the complete opposite end of the spectrum – humbling himself entirely, like the Tola’as and the hyssop. He must instead retain a balance. Despite his biting lesson in humility, he must like the cedar, not give up his backbone and sense of resolve.

Passivism and humility can be great virtues when one’s own will and ego is at stake. However, humility and passivism are not the proper response to the pain and degradation of others.

Passivism that comes at the expense of others is in fact unequivocally wrong. In such instances one must, resort to the “Cedar” quality within oneself – to stand tall for what is true and just. The latter is certainly the case with regards to the Divine will and way of life.

In the above light, the Baal Shem Tov’s aphorism – that what is perceived in others is a reflection of one’s own blemishes – would apply to instances where the perceived misconduct is directed against one’s personal self and ego. However, when the affront is directed towards a fellow human being, or against the Heavenly Creator and His divine code, it is the wrong time for humility and passivism, as the verse states: “Thou shall not stand idly by the shedding of the blood of thy fellow man.” Leviticus 19:16)

And yet, the above explanation falls considerably short. For are we really supposed to ignore offences that are committed against our own self. Is one not supposed to feel the slap in the face, or is he just meant to ignore it? Must we, for ourselves be meek, bear injustice, malice, and rash judgment? Since when has “Turning the other cheek” become a Jewish idiom?

The Tzemach Tzeddek, in his renowned discourse on Ahavas Yisroel, maintains that it is not reasonable to expect of us to be oblivious to the wrongful behavior of others; we are not asked to deny blatant reality. What is asked of us is not to judge the motivation behind the conduct.

While the inappropriate conduct is blatant and obvious for all to see and judge, we must give the perpetrator the benefit of the doubt as to the cause and motivation of his adverse actions, just as we are wont to do with regards to our own misconduct.

Much as in the case of Tzara’as – the very focus of this week’s Parshios Tazria and Mitzora – proper measures must be taken to ensure that a correct diagnosis is made, so must our judgment regarding all misconduct be untainted and unbiased.

While the Talmud (Arachim 16a) asserts that Tzara’as is brought on by one or more of seven sins aimed against fellow man – slander, murder, perjury, debauchery, pride, theft and jealousy – and the violator must be identified and called out, it is the Kohen and the Kohen alone that is permitted to make the call.

It is not the Kohen’s expertise that makes him so valuable; he may in fact lack the expertise regarding the complex nature of Tzara’as lesions and the multiple accompanying laws and must hence rely upon the advice of a non Kohen expert. It is nonetheless the Kohen and not the expert who is empowered to render the final judgment.

The reason for this is that since the Kohen is recognized by the Torah as a “lover and pursuer of peace and maker of peace among the people” (Pirkei Avot 1:12). The Kohen is described in Judaic literature as “Ish HaChesed,” a man of kindness. This facet of his core anatomy is expressed in the Torah by virtue of his divinely ordained role as the Blesser of Israel, through the priestly benedictions. In fact, the blessing recited by Kohanim prior to discharging their priestly duties of blessing the Children of Israel, declares: “Blessed are You G‑d . . . who has commanded us to bless your nation with love.”

There is hence no doubt as to the integrity of his ruling. While another person may be tainted somewhat by bias, the Kohen is sure to have the best interest of the subject in mind. The above notwithstanding, there are times when even the Kohen must proclaim an individual to be Mitzorah.

This principle holds true with regards to our individual interactions as well. One must indeed take proper measures to confirm the accuracy of his discovery and only judge the action not the motive. Still, this does not negate recognizing the harmful conduct and responding with the appropriate counteractions.

This message is highly apropos in our modern day and age when many, in the name of open-mindedness, have a tendency of being extremely flexible and passive on issues of morality and religious values.

Their progressive-self is expressed in various forms of leniency regarding the sanctity of human life and other aspects of higher Divine principles. They seem to have all the give when the skin, as it were, is off G-d’s back, yet, when the skin is off their own back – when someone steps on their toes, or crosses their will – all hell breaks loose. Gone is the generosity, flexibility and open-mindedness. They are as intransigent and unforgiving as can be.

This may explain why our progressive and open-minded society is so permeated with divorce, road rage and abuse and intolerance of all sorts.

We ought to take to heart the lesson offered to the Mitzorah in our Parsha: Tolerance and flexibility do not amount to “Turning the other cheek.”

Flexibility and passivism may be virtuous at one’s own expense. They are however not quite as virtuous at the expense of others, especially not at the expense of our Heavenly Father and His divine code of morality and holiness. There is a time and place to call a Mitzorah, a Mitzorah!

By our taking to heart the above lesson we will certainly improve our lives and that of the surrounding world both physically and spiritually and hasten thereby the coming of the righteous Moshiach BBA.

Well it seems

Lashon Hara is rampant these days So also the tongue is a small part of the body, and yet it boasts of great things. See how great a forest is set aflame by such a small fire! And the tongue is a fire, the very world of iniquity; the tongue is set among our members as that which defiles the entire body, and sets on fire the course of our life, and is set on fire by hell.

Milhouse

The Baal Shem Tov’s teaching is not about the other person, it’s about you. The question he’s addressing is not what the other person has done, but why you were shown it. Since he held (contrary to what most rishonim believed) that everything is behashgocho protis, it follows that if there was no reason why you needed to know about someone else’s fault you would not be shown it. Not that you would be blind, but that you would just not happen to come across the evidence of it. You wouldn’t be there when he did wrong, or when someone was talking about what he did.

Now there could be a number of reasons why you needed to find out about him. If you are a rov or dayan and are responsible for correcting his behaviour, then you need to know about it, and you will be shown it even if you are a tzadik gomur. The Baal Shem Tov was not talking about such a case. Yoshiyahu needed to know about the avoda zara that was going on under his nose, and he ended up dying because he didn’t know about it.

But for most of us, we have no need to know about other people’s faults, unless there is a lesson we can learn from it. So the Baal Shem Tov says that when we find out about something we should ask ourselves why we were shown it, and look to learn that lesson for ourselves.

Now clearly this can only apply to wrongs that an individual comes to perceive in others, wrongs that an individual is shown from Above. It can’t apply to wrongs that are so famous that one can’t live in the world without coming to know of them. We are not blind, and it’s not hashgocha protis that we have heard of famous villains. It’s impossible not to have heard of them. So the Baal Shem Tov’s teaching would not apply to them.

GREAT!

may we take to heart the lesson of tolerance and flexibility and improve our lives and hasten the coming of moshiach gut Shabbos . beautiful

Shabsi

The question has already been answered by the Rebbe. See Likeutei Sichos Chelek 10 Parshas Noach.

Milhouse, Nice try.

i have ADD

can someone summarize that

Jay

Why did you and your congregation interpet the BeSHT’s statement as “do not judge others”? Why not interpret it at face value: The world — with all its apparent good and evil — is really a representation of our own inner state. We can and should exercise outwardly directed discernment (what you call “judgmentalism”) and we can and should strive to improve the outer world, but we should see that outer work as corresponding to an inner work that is designed to perfect ourselves. And we should not focus primarily on the outer work. We should know that by rooting out the error within ourselves, we can most effectively diminish the evils of the world. We should not renounce the outer work by way of passivism, but as we work outwardly, our attitude should be that there is no “other.” The blemish we see on our fellow is our own blemish, but the unjust persecution we see our fellow suffer is our own persecution. Either way, we must act — inwardly and outwardly — for the perfection of God’s world. Most of the time, we are not in a position to prevent or mitigate an outward atrocity, but we are always in a position to work on ourselves. We should do our holy work in both ways, knowing that they are really one.

Jay

To sum up, the passivity that we see in our fellow is our own passivity. Our fellow’s failure to take action is our own failure to take action. Therefore, we must act if we expect others to do so.