Tradition and Trendiness Coexist in Gentrifying Montreal Neighborhood

by Menachem Posner – Chabad.org

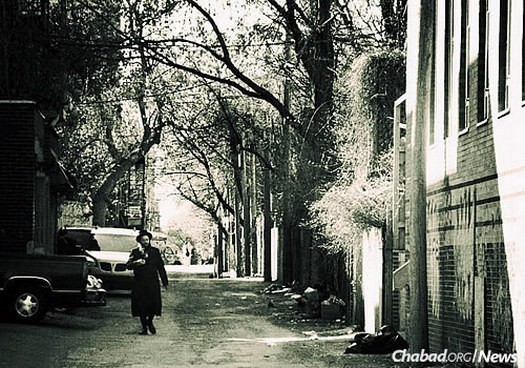

On the northwestern slope of the iconic mountain that gave Montreal its name, the Borough of Outremont is a mix of stately but crumbling townhouses, converted warehouses, sleek luxury condo buildings, rambling mansions, and bars and boutiques common to an up-and-coming urban community.

The neighborhood is the seat of an established French-Canadian population and a growing Chassidic community that never moved out when most Jewish people left for the suburban promise of backyards and bucolic living during the 21st-century postwar building boom.

In recent years, Outremont and neighboring Mile End have also seen an influx of young people reflective of Montreal’s diverse population, including many Jews who are returning to the very same streets that their grandparents left decades earlier. One busy block on Park Avenue (the main thoroughfare), for instance, features a Satmar synagogue, bars, restaurants, a Yiddish printer, art galleries, a library, a natural store, hipster shops—and the local Chabad center.

Yet until recently, the shul-goers and the bar-hoppers didn’t mix.

“We simply had no idea how many Jews were living in the same blocks as we were,” says a local yeshivah teacher, known to all as Reb Aharon. “We would walk past each other on the street never realizing that we were one people.”

‘A Beacon of Light’

Now, like many others in the community, Reb Aharon and his family regularly host young trendsetters at his home on Shabbatand Jewish holidays, largely a result of the dedicated work of Rabbi Yudi and Bruchy Winterfeld, Chabad-Lubavitch emissaries to Outremont and a cluster of other nearby neighborhoods.

“It’s unbelievable to think what one couple can accomplish,” says Reb Aharon. “They came in and made an upheaval in the community. We who had been living here for decades never realized how many Jews lived here. In no time, they found them. Even before they moved to the neighborhood, for their first Passover, they brought a caterer and set up a seder for 24 guests; it was mind-boggling.

Now, Rabbi Winterfeld is a fixture in the community, riding his bike with asukkah on the back for Sukkot and with a menorah on it during Chanukah. Chabad Mile End, as it is known, has become a beacon of light for the neighborhood.”

One of the regular guests at Reb Aharon’s table is David Prince, who often comes together with a French Canadian female friend currently in the process of converting to Judaism under the auspices of a local Orthodox rabbinical court.

Prince says he has met many Chassidim from a number of groups at the Winterfeld’s Chabad center. “It has this amazing cool vibe, where Jews of all types come together. I’ve met people from Belz and Satmar,” he says, “and they have been very gracious and open, inviting us to their homes for Shabbat dinner.”

Regular Shabbat meals have exposed Prince (who has been keeping Shabbat for several months) and his companion to the palate of traditionalAshkenazi cooking (his mother is Moroccan), including kugel, kishke and other staples at the Chassidic tables they have frequented. In fact, he reports that she has begun cooking cholent, much to the amazement of her French Canadian friends.

“I was surprised by how open they are,” says Prince, who grew up in the heavily Jewish suburb of Côte-Saint-Luc and studied at the Chabad-run Rabbinical College of Canada as a child before transferring to public school. “There is a community spirit. Beyond just hanging out with people like me, I also have an outlet in a community that I was previously aware of, but had never really interacted with.

“Their priorities are different than other people I generally hang out with,” he reflects. “They concentrate on G‑d and their family. At the end of the day, they are amazingly optimistic people, but they share the same ups and downs as me. They work day in and day out to support their large families. Though it’s supposed to be a Jewish trait to kvetch, I have never heard anyone complain.”

Prince recalls going with his business partner to evening services at the local Belz synagogue.

“We were the only two people in the men’s section not wearing black. My pink shirt and his blue one made us stick out like two sore thumbs,” he recounts. “But we felt like celebrities since every other person came over to shake our hands. They were just so excited to have us there. It was a rock-star welcome!”

‘An Integral Part of the Mix’

For his part, Reb Aharon says inviting people over for Shabbat is something he always had in him. “I grew up in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn and I would go to see the Rebbe [Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory] almost every Shabbat. My father, a Holocaust survivor from Galicia, would often bring home guests who were visiting 770 [LubavitchWorld Headquarters] for Shabbat meals, so the Lubavitch open approach is something I’ve always treasured.”

Winterfeld affirms that local Chassidic support has been crucial to his organization’s success from the get-go: “When we had our first services forRosh Hashanah in 2011, Chassidim prayed with us to make sure we would have a minyan [a prayer quorum of 10 Jewish men], and they’ve been an integral part of the mix ever since.”

When the Winterfelds were looking for a place to host their Sukkot celebration, local residents came to the rescue again. At a fundraiser for Chabad at one of the neighborhood synagogues, the rabbi mentioned that he was looking for a place to build a sukkah. Immediately, someone offered use of his own, and the family of five was joined by 25 others for a meal that holiday.

The rabbi says a paradigm shift has taken place in the Chassidic community. “Years ago, people would have felt strange saying ‘Good Shabbos’ to someone from the outside. Now, they’re on the streets shaking the lulav with their neighbors, giving out menorahs before Chanukah and inviting them into their homes.

“We just moved into a trendy new loft, which has allowed us to really expand our events,” he continues. “We had 200 people in attendance for the High Holidays. If you’d look around the room at any given moment, you’d probably see around 25 percent Chassidic families sprinkled in among the others.

“But we don’t even look,” he states simply. “Everyone is a Jew, and that’s what counts.”