The Untold Story of the ‘Are You Jewish?’ Guys

by Mordechai Lightstone – Chabad.org

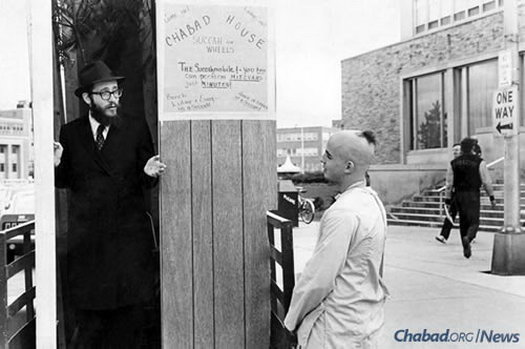

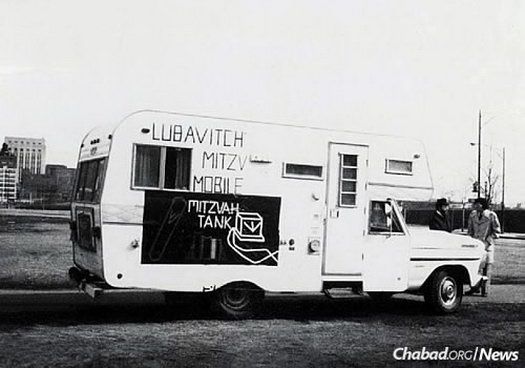

Hailing a yellow cab, grabbing a slice of pizza after a Yankees game, strolling through Central Park . . . these are some of the indelible parts of a New York City experience. So, too, is the sight of yeshivah students clamoring from a converted RV—better known as the “mitzvah tank”—tefillinand Shabbat candles in hand as they ask tourists and locals alike: “Excuse me, are you Jewish?”

The mitzvah tanks have become an iconic fixture in New York City and beyond, referenced in the media and popular culture throughout the world.

Yet despite their near ubiquity, the origins of the mitzvah tanks are largely unknown. To many, they are an accepted landmark, an expected part of the urban terrain.

Rooted in the unique challenges facing American Jewry during the second half of the 20th century, these “tanks against assimilation” go back 50 years to a pivotal time in Jewish history: the 1960s-era hippie movement, the start of the Six-Day War in 1967 and the launch shortly beforehand of the Tefillin Campaign by the Lubavitcher Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory.

Leading up to and following Israel’s miraculous victory, the Rebbe’s mitzvah campaign served also as a means for expressing Jewish pride, instilling Jewish identity, and inspiring spiritual exploration and expression, all of which were particularly needed in post-war America.

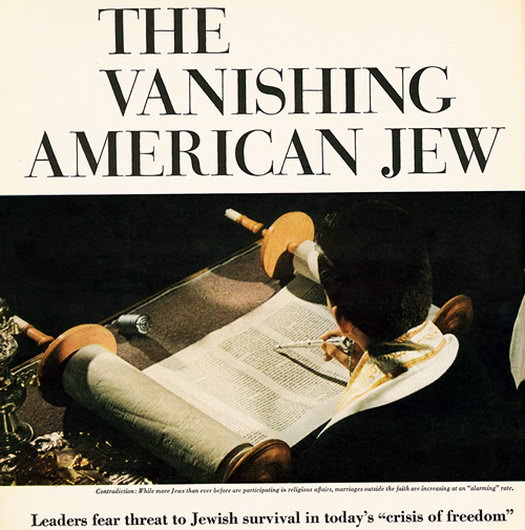

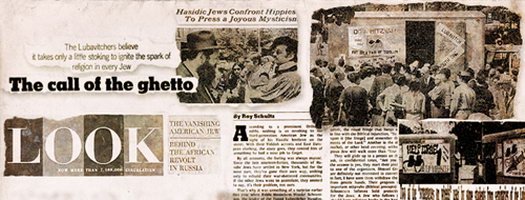

‘The Vanishing American Jew’

Post-World War II and the Holocaust, Western Jewry faced a daunting challenge. Throughout the world, Jews whose ancestors had lived in Europe and Russia during the 19th and early 20th centuries sought to leave the pain of those places and their religious traditions behind. In America, Jews began to leave the confines of urban Jewish enclaves for the growing suburbs. Spurred by decline in anti-Semitism and the promise of greater opportunity, many sought to blend their identities into the greater melting pot of Western ideals and culture. A new generation of Jews was being raised without regular Jewish education or synagogue attendance, encouraged to be more like their non-Jewish neighbors.

Perhaps no single headline summed up this trend in America more than one in Look magazine two decades after the war. Its May 5, 1964 cover story, titled “The Vanishing American Jew,” stated that “new studies reveal loss of Jewish identity, soaring rate of intermarriage,” a future where “Judaism may be losing 70 percent of children born to mixed couples.”

In the midst of this quagmire of Jewish identity, a new tool in the battle against assimilation burst on the scene in the summer of 1967: the “mitzvah mobile.”

Converted trucks from the Hertz rental-car company were transformed into ad-hoc synagogues, complete with Jewish books and religious accoutrements, including tefillin and Shabbat candles. Staffed by young yeshivah students in New York City, the vehicle—and the idea behind it—quickly picked up steam.

It heralded a paradigm shift in U.S. Jewish identity. If until then Jewish expression could be summarized more quietly as “Jew in the home, American in the street,” the vehicles represented something entirely new. Jewish identity was exhibited loudly—and proudly—outside, no longer sequestered to the synagogue or yeshivah. In the words of the era, Judaism demanded to “be here, now.”

The RVs converted into mobile Jewish centers were Jewish pride writ large: bold, brash and ready to engage the public.

1962: The Mitzvah Bus in the Age of Mad Men

The idea of using mobile homes to encourage and enable the performance of mitzvahs on public thoroughfares had its origin in the fall of 1962, recalls Rabbi Simcha Piekarski, who at the time was an older yeshivah student in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y.

“One day, I went to a local diner for a cup of coffee,” says Piekarski. “It was one of those places where you could sit and schmooze.” A local businessman and Chassid, AaronKlein, approached him with a novel idea. Noting the bookmobiles used by some libraries to serve communities in remote areas, Piekarski recalls Klein saying: “Wouldn’t it be great to have a bus that traveled around with Jewish books?”

Always someone to embrace a novel idea, Klein paid to have a Navy surplus bus refurbished, painting it in shades of blue and orange, with handsome lettering on the outside and an attached speaker system to play Jewish music.

At the time, Rabbi Shlomo Cunin was a yeshivah student who worked on building a custom shelving system to house the bus library. At the Rebbe’s suggestion, a special space was added to the back for men to don tefillin.

“We were young people,” Cunin reflects on the project. “We knew how to speak in a way that Americans could understand, in a way that would get their attention.”

Here was a chance to brand Judaism, to take it to the streets, making it more approachable and accessible to modern American Jews.

Officially dubbed the “Merkos Mobile Library,” it got much attention and caught the eye of The New York Times. A November 1963 headline announced a “Mobile Library Being Used By Hasidic Jewish Group.” Cunin was tasked with driving the bus each week to the Bronx, where he’d park it in front of Jewish communal centers. He’d turn up the music, set up tables and chairs, and encourage people to peruse the library on wheels and put on tefillin.

When Cunin moved to Los Angeles in 1965, he brought the idea of a mobile Jewish library with him. Facing opposition from a Jewish establishment uncomfortable with overt Jewish expression, the rabbi took matters into his own hands.

Finding a trailer for sale by a Fox Studios executive—Cunin, who today is director of Chabad of the West Coast, managed to get a 35-foot behemoth for $5,000, no money down—he transformed it into a mobile station for Jewish engagement.

Cunin drove the trailer up and down the West Coast. “We went to schools, to military bases,” he says. “I drove it all the way to Sacramento. People came in and it was like entering a new world; it blew people’s minds.”

The trailer played a pivotal role in Jewish outreach; it went from a resource for books to a robust hub for Jewish practice. Now on two coasts, these vehicles were poised to help affect the masses at a decisive moment in modern Jewish history by providing Jewish content to a post-Holocaust generation searching for greater meaning and purpose; and by laying the groundwork for the widespread use of these vehicles during the Tefillin Campaign launched in the days leading up to the Six-Day War, when the Rebbe called on Jewish men and boys age 13 and older around the world to unite in fulfilling the mitzvah.

‘Drop Into the Old World’

Throughout the spring of 1967, tens of thousands of enemy troops gathered ominously at Israel’s borders. World leaders and the media painted a bleak picture for the Jewish state, with Jews fearing a “second Holocaust.”

On June 5, 1967, war broke out between Israel on one side and, on the other, Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Iraq and Lebanon. Over the course of the next few days, the armies of the five nations that attacked Israel on three fronts were miraculously and decisively brought to their knees.

Seemingly on the brink of annihilation, Israel had reclaimed key parts of its ancestral land as a result of what would be come to be known as the Six-Day War. Images of Israeli soldiers donning tefillin and openly weeping by the Western Wall were seen all over the world. Jewish pride swelled universally.

At the same time, America’s youth, steeped in the new counterculture, was undergoing a tectonic shift that summer—“the summer of love.” Looking for inspiration, some young Jews turned to Eastern philosophies, rock music, communes and drugs.

The Rebbe looked beyond the younger generation’s behavior, seeing larger notions at work. He would describe the rebellion of young people as emerging from a positive fire in their souls that refuses to conform, that is dissatisfied with the status quo, that cries out that it wants to change the world and is frustrated with not knowing how to do so.

Donning tefillin represented a bridge to Judaism, encapsulating both the newfound Jewish pride and the search for new spiritual consciousness. At the time, it seemed entirely congruous for a Chabad rabbi—in this case, Rabbi Moshe Feller of Minnesota—to share the stage with a hippie from San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood and a Black Panther activist at the regional B’nai Brith Youth Convention in St. Paul to discuss “The Right to be Different.”

The Rebbe’s campaign was just revving up, and the yeshivah students tasked with the mission, recalling the mobile libraries, created a vehicle to deliver it: the “tefillin mobile.”

The New York Times described the truck in a 1968 feature article. “[A]mid the hippies, the peace marchers, the Good Humor men and the hundreds of Sunday wanderers in the warm sun,” of Washington Square Park “a big, yellow truck called the “Tefillin-Mobile” with “lively Hasidic songs and marches blaring from the loudspeaker” brought “flocks of people” over to the young enterprising yeshivah students.

Rabbi Samuel Schrage, an assistant to New York City Mayor John Lindsay and a community leader in Crown Heights, was on hand. “Young men, especially Jewish young men, are searching for mystic experiences like LSD and pot, and gurus and maharishis; we can give them mysticism,” Schrage was quoted as saying.

“Across the park,” the paper notes, “a hippie sang “Shout, shout, shout/Let’s drop out.”

Schrage replied: “Let them drop into the Old World.”

One such person to do so was Harold Mosner—a 29-year-old copy editor for Eye magazine, a short-lived attempt by the Hearst Corporation to capitalize on youth culture—who was attracted by the vehicle’s signs.

“They’re just great,” Mosner told the reporter after donning tefillin for the first time in 15 years.

As they began to spread, the tefillin mobiles proved effective in speaking to young Jews around the country. Others started noticing the impact and sought out this novel form of engagement, including a request for one of the vehicles from the North American Federation of Temple Youth Camp.

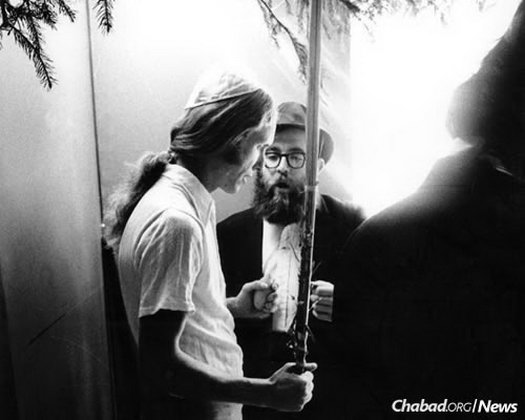

Rabbi Nosson Gurary, director of Chabad at the State University of New York at Buffalo, heralded an era of mobile Chabad centers serving college campuses and surrounding communities when he brought one of the vehicles to his area. The truck, donated by an alumnus of the school, was an instant sensation. Jews who would otherwise shy away from Jewish practice were drawn to it.

“[It] was a really powerful vehicle to meet new people,” he recalls. “We would park it by the student union, and all kinds of students who wouldn’t otherwise approach us came over.”

He notes that “we could transform it for other uses as well. During Sukkot, we could add a sukkah in the back.”

A picture taken at the time shows a Gurary engaged in earnest conversation with a young Jew wearing the clothes synonymous with a Hindu sect. Standing in the doorway of a sukkah on the back of the mitzvah mobile, Gurary, dressed in his black coat, is framed by the leaves of the sechach and a sign announcing “The Succahmobile! You too can perform mitzvahs in just minutes.” He is beckoning with his hand, inviting the young Jew, his head shaven save for a top knot, to come in.

1974: Tanks Against Assimilation

Though the use of tefillin mobiles continued, they had not yet solidified their places as the vanguard of Chabad’s outreach activities.

On May 15, 1974, in the northern Israeli city of Ma’alot, a Palestinian terror group took hostage 115 Israeli students and their teachers on a field trip. Ultimately, 25 hostages, mostly children, were killed. The news, just months after the bloody Yom Kippur War, rocked the country.

In New York, the Rebbe urged Jews the world over to do what they could in the wake of the carnage by encouraging other Jews to take positive action.

On June 5, the 15th day of the Jewish month of Sivan, the Rebbe underscored the critical nature of the mitzvot in what was then his five-point mitzvah campaign: To encourage world Jewry to purchase Jewish books for their homes; to study those books; to affix kosher mezuzahs on their doorposts; to give charity; and for men to don tefillin.

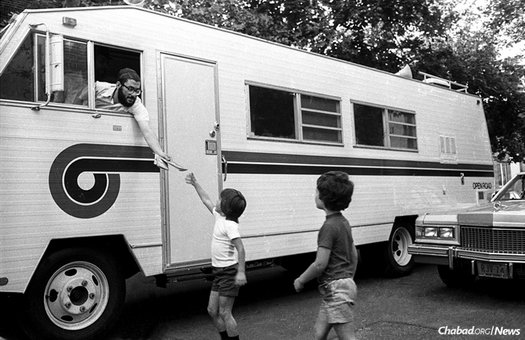

Rabbis Sholom Duchman and Yoske Gopin, two yeshivah students in Crown Heights at the time, were moved to action. “In the past, students had rented trucks for the mitzvah mobiles, but it was never a permanent thing,” recalls Duchman.

Approaching the Lubavitch Youth Organization, the organization responsible for the tefillin mobiles, they got the funds to rent a couple of trucks for an extended period of time. “We grabbed a bunch of tables and chairs from [the synagogue at] 770 [Lubavitch headquarters],” relates Gopin, “loaded them in the two trucks and set off.”

The initiative proved immensely successful. The next week, five Hertz trucks were rented. “We began renting more trucks, adding furniture, tweaking the layout to make it more comfortable,” explains Gopin.

Each truck had a steady driver and “commander” in charge of it, with 10 other yeshivah students assigned to ride in the back on a rotating basis. The trucks became an outlet for students to use their personal talents for the greater good.

Gopin recalls one classmate who was particularly talented with electronics. “He would be up at night, rigging each tank with the proper wiring, speakers and amplifiers to play the music.”

Another student painted a picture of two pairs of tefillin with their straps wrapped around their sides like the treads of a tank.

The trucks became “Mitzvah Tanks” in 1974 when Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky—a member of the Rebbe’s secretariat and spokesperson for the Chabad-Lubavitch movement—informed the Rebbe that New York Times reporter Irving Spiegel would be visiting 770, and the Rebbe referenced the painting on the truck.

“Tell him these are our tanks against assimilation,” the Rebbe told Krinsky.

The trucks at last had a name.

Over the course of the coming weeks, operations expanded rapidly. Up to seven Hertz trucks at a time were rented by Lubavitch Youth Organization. Every morning they’d fan out across the city, bringing dozens of yeshivahstudents, tefillin and Shabbat candles in hand.

“The work was exhausting,” recalls Duchman. “We’d be out until sunset,” as late as 8 p.m. in the summer, “standing outside all day.”

The mitzvah tanks became an instant sensation. That summer, Newsweek,Time and The New York Times ran stories on the tanks, as did The Chicago Tribune. In a feature-length article in the Times, titled “The Lubavitchers believe it takes only a little stoking to ignite the spark religion in every Jew,” reporter Ray Schultz explained the surprising nature of the tanks:

The Lubavitchers have been . . . on campus and in the synagogues, but they never went quite this far.

. . they hired fleet of Hertz trucks, and began driving up to such spots as Wall Street and Times Square and confronting startled American Jews, on their lunch hours, with an urgent call to ‘identify!’ ”

The Rebbe’s Army

The name “mitzvah tank,” with its militaristic overtones, was intentional. Over the course of the summer, the Rebbe spoke about the nature of the name, explaining that they were not merely passive vehicles to deliver mitzvot to Jews around the city, but served as a proactive attempt at facing Jewish assimilation and loss of identity head on.

Expounding upon the Hebrew names of three sections of the Talmud(Taharot, Nezikin and Kodashim), which together comprise the word “tank” in Hebrew, the Rebbe explained how to effectively reach out to other Jews: The work of the “tankist” needed to be done with purity of heart and eschew any personal agendas. The tankist needed to not only avoid any hint of negativity, but to endow the world itself with a spirit of holiness.

Using military terminology is hardly new in the Chassidic tradition. When Napoleon marched across the Russian Empire, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of Chabad, sent his Chassidim to find out the tune the French troops marched to, so as to claim it for the Jewish people. Later, Chassidim under the brutal thumb of Communist Russia would often subvert Soviet military marches and concepts in their battle against oppression. Perhaps most prominently, when the Rebbe launched Chabad’s international children’s club, he named it Tzivos Hashem, a biblical term for the Jewish people meaning “The Army of G‑d.”

In a Jan. 21, 1982 letter, the Rebbe directly addressed a question about the seemingly “glorification of the military and an aggrandizement of arms, wars and battlefields.”

“Of course, the Torah does not glorify militarism, war and the like,” the Rebbe responded. On the contrary, he said, “its ways are ways of pleasantness and all its paths are peace.” The terminology was employed as an act of proactive defiance of the negative, subverting and reclaiming the concept of war for the specific purpose of emphasizing goodness, G‑dliness and humankind’s eternal struggle against evil.

Thus, the only kind of “battle” people were being called on to wage was against the baser urges of individuals’ own worst instincts. The “secret weapon” of the Jewish people throughout history, the Rebbe wrote, were mitzvahs such as tefillin and Sabbath observance; they represent “the secrets of Jewish strength throughout the ages.”

Indeed, the entirely spiritual and peaceful nature of the “tanks” left a positive impression on members of Israeli military leadership. Gen. Yossi benHanan, who served at the head of Israel’s armored corps, praised them.

“Their weapon system is not a gun, their ammunition is not projectiles, but I suggest that those mitzvah tanks do have a very decisive weapon: Which is the spirit of Israel,” he said. ”Those tanks arrive on the battlefield and they bombard their targets with the right kind of ammunition: Which is the heritage and tradition of our nation.”

1982: On the Front Lines

While the mitzvah tanks were agents of peace, the service they provided took them to literal battlefronts. During the 1982 Lebanon War, they received special military dispensation to visit Israel Defense Forces units in Beirut. Mitzvah tanks could be seen near the frontlines of the conflict, bringing tefillin and other opportunities to perform mitzvot to spiritually fortify the Israeli soldiers.

A few years later, Israeli Ambassador to the United Nations BenjaminNetanyahu—later to become prime minister of Israel—remarked that these tanks “sustain that heart [of the Jewish people] with Jewish love, Jewish spirit, [and] Jewish faith.”

“When I was a soldier in the Israeli army,” he continued, “I remember when Chabad came, they lifted my spirits, the spirits of my soldiers, my fellow officers.”

In 1989, Rabbi Levi Baumgarten was tasked with running a daily mitzvah tank. By his estimation, some 500,000 people have come aboard for regular classes, prayer sessions, to study or to do a mitzvah.

“The logistics of running the tank requires a lot of patience,” says Baumgarten. “But it’s a blessing I live with every day. The ability to reach so many people is just amazing.”

Through the years, the tanks have become the vanguard of Chabad’s worldwide presence, bringing “mitzvahs on the spot for people on the go.” They can be found on the streets of Los Angeles, Chicago, Montreal, Sao Paulo, Paris, London and Tel Aviv. In Australia, Chabad of Rural and Regional Australia dispatches teams of yeshivah students aboard a mitzvah tank to reach Jews deep in the Outback. In San Francisco, there’s even a “mitzvah cable car.”

Amy Keyishian, a freelance journalist in the San Francisco Bay area, recalls her first encounter with a mitzvah tank years ago. She was struck by “the generosity of them,” showing other Jews how to engage with rituals in an instructive and nonjudgmental way. “Many of us really hunger for the tradition our parents rejected,” she adds. “It’s very comforting to be near it and to take some of it back to our own Jewish spaces.”

Mark Oppenheimer, a lecturer in English at Yale University and a noted commentator on Jewish life, sees in the proliferation of the mitzvah tanks a unique contribution to Jewish identity. “Most American Jews have the luxury of passing [as non-Jews], of blending into the white majority,” he says. “Being called out on the spot and asked ‘Are you Jewish?’ can be painful for them. It’s a violation of that expectation of privacy.”

Keyishian agrees: “When you think about it, being visually Jewish by choice is unbelievably punk rock.”

The very nature of the mitzvah tank’s ability to explore Jewish expression in the public space creates a tremendous opportunity for building Jewish identity.

“The mitzvah tank is asking Jews, ‘Are you a Jew?’ ” notes Oppenheimer. A Jew meeting a young yeshivah student on the street is confronted with a powerful question: “Is this central to your identity enough that you’ll own it on the street, talking to a stranger?”

“It puts people on the spot and forces them to think about their identity, to recognize it,” he says. “There are a lot of Jews, whether or not they admit it, who are grateful for Chabad insisting on giving them some Judaism in their lives.”