Rabbi Demonstrates Ancient Skill of Torah Making

DALLAS, TX — A turkey feather. The tendons and tail hairs of cows. These are the basic tools of Faitel Lewin’s trade.

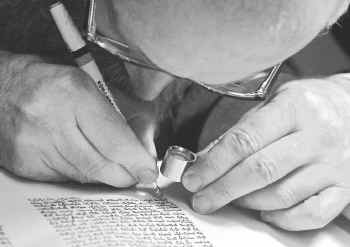

Rabbi Lewin is a sofer, a modern-day practitioner of an ancient and essential Jewish craft: scribing Torahs. With his turkey quill pen, he writes the full text of the Bible’s first five books, Genesis through Deuteronomy, in Hebrew on sheets of parchment prepared from animal skins. Then he wraps and stitches them into a pliable scroll with his bovine threads.

“My father was a scribe,” he said. “I was born into this.” Now 45, he’s been a sofer for half his life.

Ordained and trained in a Chabad community in Brooklyn, New York, Rabbi Lewin recently visited Dallas to be part of the dedication of a new Torah for Akiba Academy, a modern Orthodox day school for children from preschool through eighth grade. Acquiring a Torah is a momentous event for any Jewish community.

Over three days leading up to the big celebration, he repaired Torahs and other ritual items for individuals and institutions in the Dallas area, and demonstrated the skills of a scribe to students at Akiba and its sister high school, Yavneh Academy.

“First, you have to find out if you have it in yourself to do this work,” he told them. “Then you study all the laws [more than 4,000 apply to Torah scribing]. After about eight months, you’re tested on them. And then you learn how to make your quills, and to write. The skill is in the point of the quill,” he said, showing how to cut the sharp corners that assure precise lettering.

Must be kosher

The scrolls from which prescribed biblical portions are read during synagogue worship must be kosher – in full accord with Jewish law. So the sofer makes his parchments and pens from cloven-hoofed, cud-chewing animals and birds without talons – no meat-eaters allowed. His jet-black inks are blended of plant and mineral derivatives mixed with water. Before beginning his work, he purifies his body in the mikvah, a ritual bath, praying there for a pure heart as well. On the table where he spreads his tools, he also places his motto: “I am hereby attesting that my writing will be for the sanctity of the Torah.”

Learning how to form the Hebrew alphabet’s 22 letters with the necessary precision takes about two years. In case of error, a letter may be scraped off the parchment and re-inked; however, if any letter in any rendering of God’s name is imperfect, the entire scroll becomes nonkosher – unfit for use in religious ceremonies. For that reason, scribes-in-training often practice on Megillot, smaller scrolls telling the story of Esther, because that is the one book of the Bible that never mentions God’s name.

he student must learn how to check scrolls already in use for signs of wear or other damage, recognizing what is kosher and what is not, and must practice making corrections. “It takes another year to connect what you know to what you see,” Rabbi Lewin said.

Inspection, repair

During his Dallas visit, Rabbi Lewin inspected and repaired six Torahs belonging to area congregations – Conservative and Reform as well as Orthodox. He also checked the smaller parchments inside about 80 mezuzahs (metal cases affixed to doors) and 20 tefillin (tiny cases worn on the body) from area households and made necessary repairs.

The handwriting of a complete Torah – 79,000 words, 304,805 letters – takes at least a year. The sofer uses a straightedge to delineate 248 columns on 80 parchment sheets, with precisely fixed margins.

Such scrolls have been written for more than 2,000 years in many parts of the world; some are simple, some elaborate. The cost of a new Torah depends on several factors, primarily the artistry of the scribing, but range roughly between $25,000 and $45,000.

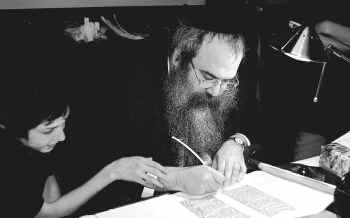

Most of Akiba’s new Torah was scribed in Israel and brought back from there by Howard Schultz, a Dallas businessman who commissioned the gift. The finishing was done by Hasofer in Brooklyn, a professional company with a staff of about 10 sofers, Rabbi Lewin among them. The final 200 letters were outlined only, left to be fully inked in the presence of the students who will be reading from it in their school chapel.

613 commandments

The Ten Commandments that Moses received at Mount Sinai are not the only ones in the Torah. The total is actually 613, and the last is to write a Torah of one’s own. Although the injunction really means to live a life of Torah study and good deeds, the opportunity to place one’s hand on the arm of a sofer as he fills in an actual letter is profoundly meaningful.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for these students to participate in this process of creation,” said Rabbi Zev Silver, Judaic studies principal at Akiba. “Our children need to know that this Torah is being given to them because they are our future.”

Rabbi Moshe Klein, head of Hasofer, also attended the final scribing and the celebration that followed. The honor of standing by him as he completed the final letter was given to Mr. Schultz, a major Akiba benefactor. His gift is a “child-friendly” scroll, smaller and lighter than most. The boys from Akiba and Yavneh designed a decorative cover for the new Torah, and girls from both schools made a quilt-square design canopy under which it was carried into the chapel.

Ben Romaner, Mr. Schultz’s oldest grandson and a student at Akiba, received a second special honor as the first person to read aloud from the new scroll.

daniel

hey rabbi dubrawsky, i see you peaking from behind there. you’re the coolest rabbi of all times!

123

very nice!! big kidush hashem.

shkoach rabbi levin!!

moishe keep going from strengh to strengh

your biggest fan....

Rabbi Klein,

May your business grow and grow, and may you continue to be able to do all the chessed that you do, and more.

Hashem should grant you Brocha V’Hatzlocha bakol.