Here’s My Story: Riots, Bombings, and Chasidic Music

Rabbi Noson Gurary

Click here for a PDF version of this edition of Here’s My Story, or visit the My Encounter Blog.

I could fill a whole book with my experiences coming straight out of yeshiva and landing on a college campus in the early 1970s.

After hearing so much from the Rebbe about the importance of shlichut, serving as a Chabad emissary, it was my greatest dream. So, two years after we got married, my late wife and I volunteered. At first, the Rebbe’s office was going to send me to Finland. I knew nothing about the country, but if the Rebbe wanted, we would have happily gone. Then they were looking into Greece, but neither of those options worked out.

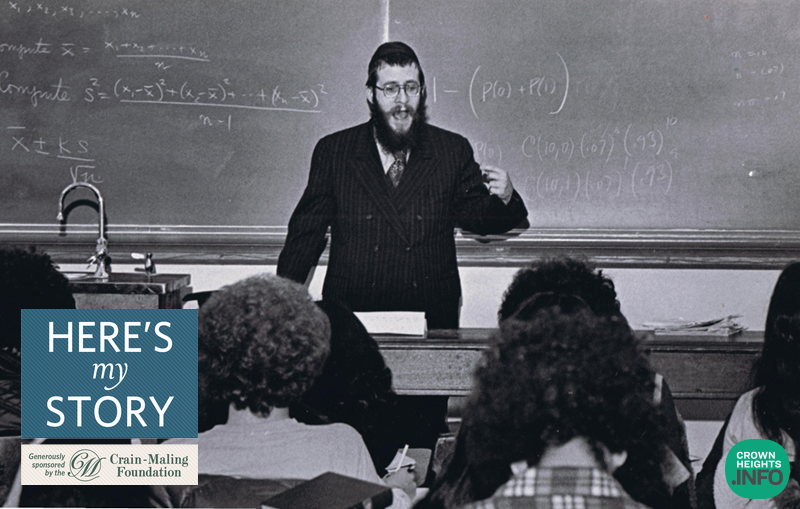

Ultimately, what did materialize was the University of Buffalo. Back then, it was a radical campus, with thousands of Jewish students. Many of them were hippies, and unfortunately, many of them were drifting into other religions and all kinds of different lifestyles. There were riots, and even bombings; it was a wild time.

The Rebbe had received letters from people in the local community describing the situation, and they had requested that someone be sent to work with the Jewish university students.

Before I left, I had a private audience with the Rebbe, in which I asked two questions.

The first was about the Vietnam War: The protests and riots on campus were mainly about the American involvement in Vietnam, and I wanted to know how to present the Jewish view on the matter — but the Rebbe advised me to explain that this issue is too complex to weigh in on without knowing all the facts on the ground. This way, I wouldn’t be taking a side in the debate.

The second question was: What to answer if someone asked me about the difference between a Jew and a non-Jew? This was a very sensitive issue in those days. If a Jew felt that he was in any way superior to others, that could be problematic.

Actually, one of my first experiences on campus involved this question. I had gone to visit the student union building, and the place was popping. Everyone there was shouting for something else; this one was shouting against the war, that one was for the war, and someone else was banging on drums.

I went to the basement, which was known as the Rathskeller. There were students playing pool there, and I struck up a conversation with one of them, a boy with long hair, like everyone in those days. “Are you Jewish?” I asked calmly.

That was all I needed to say. Turning red, he shot back: “What difference does it make?” Suddenly, a circle of hippies began forming around me. The boy went on: “Is there a difference between a Jew and a non-Jew? If not for the respect I have for my father, I would knock you down right now.”

The Rebbe told me to address this question in the following way: “When you build a home, everyone involved has a different role and a different job description — electricians, plumbers, carpenters, and so on. Everyone has a shared purpose, which is to collectively build the home, but if one tried to do another’s job, there would be chaos. So too, the Jewish people have a mission that they share with the other nations of the world, with a common goal, but their jobs are different.”

Thank G-d, although I didn’t have the opportunity to share the Rebbe’s answer the first time I encountered the question, I found the courage to go back again, and then again.

One of the first things I did was set up a table in the union building, placing a large picture of the Alter Rebbe, the first leader of Chabad, on the table, along with Jewish artifacts, like a shofar and a kiddush cup. I also had chasidic music blasting from speakers and looked completely out of place, which attracted everyone’s attention. Slowly but surely, students came over — hippies, communists, and kids from every background — and I invited them to our Chabad House.

One year after I arrived on campus, I received an instruction from the Rebbe that seemed to defy all reason. I had written to the Rebbe about my efforts to organize some Torah classes, and in his answer, he wrote that I shouldn’t teach any classes on campus unless they counted for university credit. At first, this seemed impossible. I had no Ph.D., and what university would accredit my classes? It was a strange answer; setting a condition like that was something only the Rebbe could do.

Right away, I put together a resume — I had been ordained to serve as a rabbi and a rabbinic judge, and had published several articles in Torah journals, all of which I said were equivalent to a college degree — and submitted an application to teach at the university. Miraculously, they approved. Without exaggeration, that semester alone I taught four credited courses, with midterm papers and finals: Chasidic Philosophy, Jewish Mysticism, Jewish Law, and Chasidic Music as Literature, where I would play chasidic melodies from the “Nichoach” series of records and then explain what the melody was about. There could be between forty and a hundred people in a course, and over the years, well over ten thousand students took them.

The Rebbe once wrote to me: “Do you have any idea how amazed I am at how many thousands of students were drawn closer to Torah and mitzvot through these courses, because” — and he underlined this part for emphasis — “of the fact that you were able to teach for credit?”

After ten years or so, the university campus moved out to the suburbs, and it became a very different scene. So that there wouldn’t be any more riots, the campus became scattered, with the buildings separated from each other, making it difficult to gather people together. This also made it difficult for me to gather people for Shabbat morning prayers.

For more than twenty years, I would spend nearly every Shabbat morning walking through the dorms, knocking on doors, climbing flights of stairs, trying to get nine students out of bed so we could pray with a minyan.

I know that my efforts did not go to waste, but having to spend hours every Shabbat just trying to bring people together could be depressing. Holidays were even worse for me: I grew up in Crown Heights, where days like Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, or Sukkot were the greatest experiences, celebrated among thousands of people. On those days, campus was very lonely.

Once, I wrote about this sense of loneliness to the Rebbe.

“Since you are doing the work of my father-in-law, the Previous Rebbe, he is with you,” the Rebbe answered. “And we are also together.”

I had always believed this, but to hear it from the Rebbe himself — that he was with me, that he knew what I was going through — there was nothing stronger than that.

On another occasion, I brought a professor to meet the Rebbe, who helped him appreciate the urgency of our work on college campuses. “Nowadays, it is like a house on fire,” he explained, “and we must save every Jew so they won’t be lost.” And indeed, so many students who had been far from Judaism — people who were drawn into other religions, or who hated religion altogether — turned around, and went on to build Jewish families. Some of their children today run Chabad Houses on college campuses themselves.

Rabbi Noson Gurary established the Chabad House of Buffalo in 1971 and has served in that role for over fifty years. He was also instrumental in establishing Chabad houses on other college campuses in Western New York. He was interviewed in November 2013 and August 2023.