Repentance and Redemption from Behind Prison Bars

by Rena Vegh – chabad.org

Amid the Ten Days of Repentance between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, the energy of forgiveness, redemption and return are in the air, and with it the questions, calculations and awareness that rises in the Jewish mind. To take a reckoning of oneself is a daunting experience. To allow others, let alone G‑d, to do so can be frightening.

‘My Redemption Process’

Mike immigrated from the Soviet Union at age 10 and grew up in a secular Jewish home. In 2014, he was sentenced to 25 years in prison for health-care fraud. Despite the white-collar nature of his crime, due to the length of his sentence he was at first placed in Metropolitan Detention Center, a medium-level security prison in Brooklyn, N.Y. Being one level beneath maximum-security prisoners meant that Mike was subjected to harsh prison politics and, despite being mostly unaffiliated with Judaism, he decided to get a large tattoo of a Star of David on his forearm to make it clear to gangs in the prison that he was Jewish and wouldn’t join them.

In 2015 Mike was transferred to the Federal Correctional Institution in Otisville, N.Y., not knowing what to expect based on his previous experience. On his first Shabbat at Otisville, he went to the Jewish chapel and was shocked to discover it set up with long tables with white tablecloths (which he later discovered were actually bedsheets) and a kosher meal prepared by Jewish inmates.

“I couldn’t believe we were marking Shabbat in the worst possible setting, but with the greatest crowd that I could ever imagine,” he said.

The experience surprised and moved Mike. The contrast between the low place he was in physically and the high spiritual planes of the holy Shabbat was unlike anything he’d felt before. Little did he know that this paradigm would follow him throughout the remainder of his time in prison.

He heard about the help the Aleph Institute offers Jewish people in the justice system, but he didn’t really understand the extent of their services until four young yeshivah students slept in a trailer in the parking lot to be able to join in the prison’s prayer services.

Mike was also introduced to Sholom Mordechai Rubashkin, who was serving his sentence in the same facility.

“Rubashkin was adamant about studying Tanya [the classic Chassidic work authored by Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of Chabad)] and he would study it with us often, no matter what anybody was doing,” recalled Mike. This and other learning partnerships quickly helped Mike find his tribe. “Serving your sentence among 1,100 men, out of which just a small fraction are Jewish, kind of makes you grow that much closer to the people you’re there with.”

The experience was transformative: “I came into prison as Russian Mike … but while there or leaving there, it was definitely Jew Mike.”

“Jew Mike” wasn’t defined by his actions, by the fact that he was in prison. He was defined by his willingness to grow and learn, and by his character. When other Jews joined the prison, Mike made sure they were protected and had the right paperwork so they could be allowed in the chapel. “I made sure that … they were never told, ‘You can’t sit at the table here with us because of what you did,’ that was part of my redemption process.”

In 2023, Mike filed a motion to the court asking for a reduction of his sentence and was granted a reduction to 15 years. This, plus some credits for good behavior, made it possible for him to be released under the Bureau of Prisons jurisdiction. He now puts on tefillin daily, something he had started doing in the early 2000s, but with a new feeling behind it, as something he does because he is a proud Jew.

“I’m very proud of my heritage. I’m very proud of my beliefs,” he said. “I will stand up for any Jew, no matter what he’s done.”

Being outside prison has also created a new understanding of what it means to return to society after making mistakes in the past: “I have definitely learned to understand what teshuvah is. That return, the coming home, in most cases is proverbial, but for me, it’s literal. I remind myself of where I was. I remind myself to be humble. I was definitely not humble before I went to prison.”

‘You’re Still a Human Being’

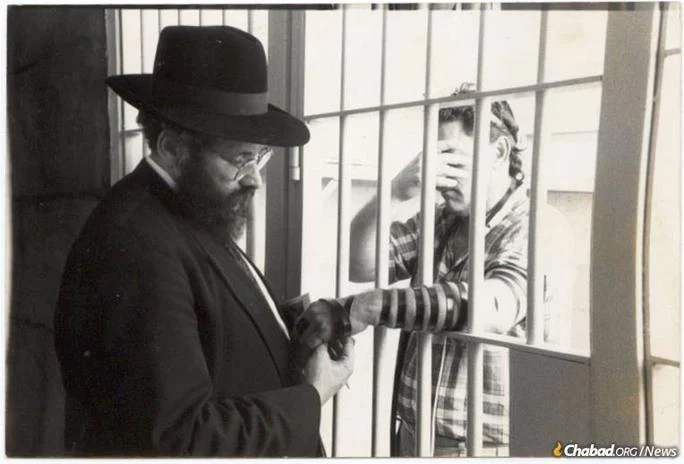

In 1981, Rabbi Sholom Ber Lipskar founded the nonprofit organization The Aleph Institute with the encouragement of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory. Aleph made it its mission to visit Jews in prison, helping them to practice Judaism and protecting them from antisemitism in the prison system. In the 44 years since its founding, Aleph has grown to become the largest Jewish organization caring for the incarcerated and their families.

They offer 25 courses to inmates on different Jewish topics to help them grow in their connection to the Almighty and get involved in the process of teshuvah—returning. In the last year, they have sent more than 100 pairs of tefillin out to Jews both in and out of prison, and countless Jewish books to prisons for reading and learning. They are advocates for Jews in prison, being their mouthpiece and ensuring they are treated safely and fairly wherever they are.

Aleph also helps the families of inmates, supporting them in whatever way possible or arranging counseling for family members.

Miami-based Chabad-Lubavitch Rabbi Mendy Katz has been a fixture of Aleph for 32 years, visiting prisons, interacting with service members to make sure they have what they need, and being a driving, steady force behind Aleph’s mission statement to help individuals no matter what they have done. “Even if you think you’re a terrible person, even if you committed the most heinous crimes, you’re still a human being, you still have a G‑dly soul. These souls need more direction than anyone,” Rabbi Katz says.

This is especially true since convicted felons have a hard time maintaining a connection to the outside world once they are sentenced to prison, as it is not uncommon for their friends and family to turn away from them.

On his visits to prisons, Katz focuses on how the inmates are holding up and if their needs are being met. After that, he does his best to build them up and support them through their process of growth and healing.

In his visits during the High Holiday season, Rabbi Katz discusses teshuvah a lot. Speaking with Chabad.org, he compared the concept of the High Holidays and going before G‑d to that of a trial in the American judicial system. G‑d offers us the option to wipe our records clean by feeling remorse and committing to making different decisions in the future. He tells the prisoners he visits, “If their judge offered them that, they would jump at it.”

And more importantly, “Just because you’re in prison doesn’t mean that you’re a bad person, and it doesn’t mean that you can’t better yourself. There’s always the opportunity for redemption.”

Judaism as a Security Blanket

Another beneficiary of the Aleph Institute is Shawn Balva, a name now well-known after the publication of his book Conviction in 2023. Like Mike, Shawn also grew up in a secular Jewish home and didn’t have many positive associations with Judaism.

When he was incarcerated at the age of 21, with a six-year sentence ahead of him, Shawn had to think long and hard about what his future would look like. Would he continue on the path he was on, or overhaul his thought processes and live a happy and healthy life?

“I thought to myself, ‘It’s Judaism.’ I don’t even know where that thought came from, but it quickly took hold as the only way to break out from the bleak path I was heading towards.”

Shawn compared the Aleph Institute to a blanket that is safe, comforting and secure. Aleph took care of whatever needs there were in prison and beyond, making sure Jewish inmates received kosher food, got access to tefillin or even proper medical care.

“It’s a scary thing to be in a jail or a prison,” he said. The nuances of prison politics are not built on love and support. “Even though you’re a part of something out there, they don’t care about you. They’re willing to get rid of you and hurt you.”

Being surrounded by such strong opposing forces with no one in your corner is an isolating and frightening experience, which is why Aleph tries so hard to make sure no Jew feels alone or abandoned, he said.

After an incident which culminated in Shawn getting punched in the stomach repeatedly as “discipline” from the members of the group he was part of in a Californian prison, he contacted the Aleph Institute and asked to be transferred to a different prison. That’s when he came to Otisville, and the differences became clear right away.

“Fifteen religious Jews … they’re throwing tzitzit at me, [a] kippah; it’s like yeshivah,” he joked.

After learning about Judaism through his studies in prison, Shawn compared his experience transitioning back to life outside prison to the Jews wandering in the desert for 40 years.

“Prison is a desert, and anyone who gets out, in a sense, is entering Israel. Now, everything that you learned, everything that was given to you, are you not only going to keep it, but are you going to continue to water those seeds that were sowed?”

Shawn described being invited for Shabbat after getting out of prison, and how he told his host that he had been in prison for armed robbery, double-checking if the invite still stood. The host told him it didn’t matter.

“It’s ironic to me. Ten years ago, I used to rob people, and now people trust me and welcome me into their homes. That’s the Jewish people. When they see that a person really changes, they welcome them back,” he reflected.

The process of rehabilitation and return to G‑d has meant dealing with self-judgement. That process of acceptance is necessary to successfully moving forward in the self-forgiveness process.

“The only person who’s been judging me unfavorably in the past ten [to] fifteen years of my life has been myself. You have to tell yourself, ‘I accept everything I did in the past and what’s done is done.’ Take account of what you did wrong, what your weaknesses are, what your strengths are, who you want to be, your purpose.”

Most crucial in moving towards changing yourself is to find a mentor who will steer you on the right path.

“Find good people that will give you advice, and make sure that they’re keeping you in check. You need somebody who can tell you straight to your face if you’re wrong or if you’re right.”

The High Holidays Behind Bars

The High Holidays bring up difficult memories for Shawn, because despite the fact that those were his first experiences of the beauty of those holidays, it was also a time in his life that has been steeped in pain.

“Prison is traumatic. And the thing about trauma is sometimes it doesn’t hit you until later. I’m OK, but you feel the effects of that traumatic experience because it’s not normal for a human being to be in prison.”

When asked about how they look back on their experiences, both Mike’s and Shawn’s responses weren’t as surprising as one might think.

Mike responded by saying, “I’m going to sound crazy to say it, but I think I’m better off for having gone through it.” Shawn echoes the same sentiment, saying he didn’t regret the experience, though there is regret involved. “I wish I could turn back the clock. Some of the most horrendous violence that I saw in my life was not on TV. It was in person. But this is who I am. It’s made me.”

However, both of them said, in no uncertain terms, that people should not commit crimes nor land themselves in prison. There are other ways to go through a redemption process.

Mike admits that he lived a life of crime before incarceration, but that the sentence he received didn’t match the crimes committed. This sentiment is a huge factor in comparing the American judicial and rehabilitation system with that of G‑d’s process of return experienced during the month of Elul and the High Holiday season.

Though a return to the “straight path” can happen, it is only a latent function of prison, not a guaranteed result. But on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, G‑d perfectly decides the next best steps for each and every one of His children, so that they experience everything they need to to set themselves on a just path and return to His ways. His process, when committed to, ensures that each person is on the path of growth, which is all that is needed to be a thriving and holy Jew.

The bigger problem, Rabbi Katz says, is not the teshuvah between man and G‑d, but rather the forgiveness needed between man and man. If someone wouldn’t want to be examined under a microscope and judged for their inevitable transgressions, they should be hard-pressed to apply the same judgement on someone else.

“That’s the message of what we do at Aleph—we’re not judging people, we’re just trying to help people regardless of their crimes. I think this is a very important lesson to the world at large. You have to be ready to forgive.”