Here’s My Story: Men On A Mission

Rabbi Yosef Minkowitz

Click here for a PDF version of this edition of Here’s My Story, or visit the My Encounter Blog.

It was a Thursday night in early 1967 and we were studying at the yeshivah in 770, when Rabbi Binyomin Klein, one of the Rebbe’s secretaries, walked over to me with a message. Rabbi Hodakov, the senior secretary, wanted to see me once the evening study session was over at 9:30 PM.

This was almost unheard of. Rabbi Hodakov would not normally call over a yeshivah student, and if he did want to see me, that meant the Rebbe had something to do with it. Had I done something wrong?

“Am I the only one being called?” I inquired.

“There are a few others,” was the answer.

That consoled me somewhat; if there was some kind of problem, at least I wouldn’t be on my own.

At 9:30, I went to Rabbi Hodakov’s office at the end of the corridor on the ground floor of 770, along with several other students. It was the size of a closet, but he wasn’t the type to mind, and somehow he managed to run the Rebbe’s entire operation from there.

Squeezed inside that office, we were informed that we had been chosen to go to Melbourne, Australia. A Chabad yeshivah for local high school graduates had just opened up, and it needed support while getting established. We would help form the nucleus of the student body, while also studying with and encouraging the local students. It was the first time the Rebbe had sent such a group — which he later called “emissary-students” — and we would be there for a two-year posting. However, Rabbi Hodakov had three conditions:

Number one, we were not being compelled to go. If we went, it had to be because we wanted to go, “happily, and with a joyful heart.”

The second condition was that our parents had to approve; and third, we had to get a doctor to confirm that we were in proper health.

“Is this coming from the Rebbe?” someone asked. We noticed that Rabbi Hodakov hadn’t mentioned the Rebbe at all.

Rabbi Hodakov was always diplomatic in the extreme, and he avoided answering this question. “If I tell you that it is coming from a certain source, you’ll feel compelled to go,” he reasoned, “and we just said that you have to go because you want to.”

“When will we go?” called out somebody else.

“As far as we are concerned, you can go tomorrow, but first you need to get the proper papers and tickets.”

Soon after, we heard from Rabbi Dovid Raskin, one of the administrators of the yeshivah, about the source of these instructions. “We didn’t even suggest any names for the Rebbe to choose from,” he insisted. “You were personally selected by the Rebbe.”

Before long, we were able to report back to Rabbi Hodakov

that we had met all the conditions, which he then relayed to

the Rebbe after the morning prayers on Shabbat.

On hearing the news, the Rebbe informed Rabbi Hodakov that he would be holding a farbrengen that day. Nobody had expected this. In those days, the Rebbe typically only led a farbrengen once a month on Shabbat and special occasions, but this was just a regular day.

At the farbrengen, the Rebbe spoke at length about our mission to Australia, by referring to the story of the upcoming holiday of Purim. As it was said of Mordechai at the end of the Megillah story: “His fame spread through all the lands.” So too, said the Rebbe, “the time has come to send people off to a far-flung corner of the world, to bring the wellsprings of Chasidut there.”

The Rebbe blessed our departing group, poured each of us a l’chaim, and as everyone sang, he stood up, clapped, and danced while singing along — all of which was extraordinary.

Two weeks later, on the night before our group of six emissary-students was set to leave, the Rebbe invited us for a private audience.

Over twenty minutes, he defined the goals of our trip to Australia, which was “to bring the light of Torah and mitzvot there, including the light of Chasidut,” as well as to influence “the entire Melbourne, then all of Australia, to turn it into a chasidic country.”

The Rebbe continued: “For chasidim, and especially yeshivah students, everything starts with the study of Torah, so this should be your primary role.”

However, he also added that in our spare time, and in a way that would not interfere with our studies, we could also work with the local outreach organizations. It wasn’t the reason we were being sent, but the work of spreading Judaism would ultimately elevate our own studies — and therefore, it became significant in its own right. The Rebbe discussed this concept at great length, citing examples from Jewish law, the Talmud, and other Torah sources.

Ultimately, though, our main task was “to study Torah continually and diligently, in a way that leads to the scrupulous performance of the mitzvot, and to serve as an example to others.” Those words, which the Rebbe reiterated several times during the twenty-minute audience, are still ringing in my ears.

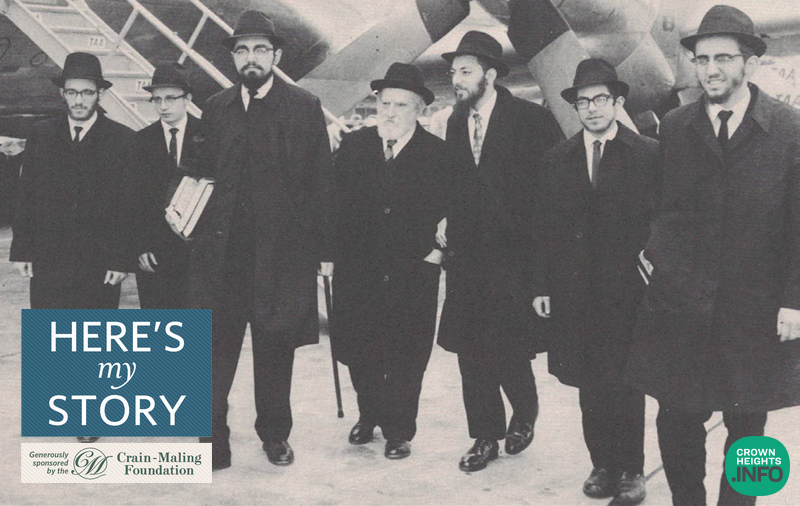

Our flight on Qantas Airways was set to leave the next afternoon. The Rebbe prayed the afternoon service an hour earlier than usual, so that we could join him without missing our flight. From there, we went straight to the cars and buses taking us to the airport. At the Rebbe’s request, the entire yeshivah accompanied us.

Then the Rebbe himself came outside the front door of 770 to see us off. It was drizzling lightly, and somebody held an umbrella over his head, while he waited for us to pull out.

We spent the next twenty-five months in Australia learning Torah, without missing a minute from the yeshivah’s daily study schedule, which started at 7:00 AM and ended at 9:30 PM every weekday.

Not long after we arrived, we were asked to teach a weekly Torah class for the local community. It would be at 9:00 PM on Wednesdays, in a private home, and we would do it on a rotating basis. But when the idea was put to the Rebbe, he immediately rejected it, while expressing his surprise at the question. Other students could teach the class, he wrote, “but not the six that have traveled there as emissaries, on a special mission… unless it is entirely outside of their scheduled studies.”

Still, there were some other opportunities for communal activities outside of the yeshivah schedule. We helped run a two-week camp during the Australian summer vacation, and I spent a week with a colleague doing outreach work in Adelaide, South Australia. During Sukkot, we went to Sydney for a few days, to go around speaking to hundreds of Jewish public-school students about Judaism.

Several years after we had come back from Australia, I was walking on Kingston Avenue in Crown Heights, when a yeshivah student approached me.

“Were you in Australia a few years ago?” he asked.

“Yes,” I replied.

“And did you go to Randwick Boys’ High School and speak about the Four Species of Sukkot?”

“Yes. But who are you?

His name is Aryeh Solomon. “When my friends and I saw you guys get up there and speak about Judaism with such confidence,” he explained, “we decided that we had to be like you. We left that public school and ended up going to yeshivah.” Today, he lives in Sydney, and is a Chabad emissary himself.

Rabbi Yosef Minkowitz has been the principal/dean of the Beth Rivkah Academy in Montreal since 1973. He was interviewed in January 2011 and February 2020.