Here’s My Story: A Whisper From The Heart

Rabbi Moshe Herson

Click here for a PDF version of this edition of Here’s My Story, or visit the My Encounter Blog.

grew up in a traditional Jewish family, in 1940s Rio de Janeiro. My mother had memories of the shtetl, of seeing a chasidic Rebbe pass by in the street, but my father had little connection to Chasidism. When I was nine, my father passed away.

My older brothers never had a formal Jewish education – a tutor came to our house a couple times a week, and that was the extent of it – but my mother decided to take me out of public school and put me in the local Jewish day school, along with my sister.

In 1949 or so, after I was already Bar Mitzvah, an emissary of the Previous Lubavitcher Rebbe arrived in Brazil, a man by the name of Rabbi Yosef Wineberg, who was also a distant relative. He had come to fundraise, but later we learned that before being sent, the Previous Rebbe had told him: “This is the first time you are going to Brazil. Remember, your purpose there is not only to receive, but also to give.” He was collecting money, but he had to reciprocate too.

So while in Brazil, Rabbi Wineberg would share words of Torah with the people he met. He came to my school and tested my class, I went to visit him with my brother, and he also paid a visit to our home.

During the conversation in our home, he asked me whether I might want to learn in a yeshivah back in New York; he could send me the affidavit I would need for a visa.

“Of course,” I said, out of respect. But in truth, it was the farthest thing from my mind; I wanted to continue my secular studies and eventually become a doctor.

True to his word, Rabbi Wineberg sent the papers, but they just sat in our house for nearly a year. When they were about to expire, I had a conversation with my mother. We decided that it would be a good idea to continue my Jewish education in America, before going to university. I had some Brazilian friends who had gone to study in New York’s Torah Vodaas yeshivah, but my mother insisted: “You received your papers from Lubavitch, so you will go to Lubavitch,” that is, to the yeshivah Rabbi Wineberg represented. I remained close with my friends in Torah Vodaas, but once I got to Lubavitch, I was happy there.

I arrived when I was fifteen years old, in the summer of 1950, just a few months after the passing of the Previous Rebbe. In Crown Heights at the time, there was a lot of talk about the Previous Rebbe’s younger son-in-law. He was then called the Ramash, but soon, after officially succeeding his father-in-law, he would simply be known as “the Rebbe.” I started observing everything going on, while paying close attention to the Ramash, and I quickly took to him. I’m not sure that I can pinpoint anything specific, but I saw something different in him. He was very genuine, and I found that appealing.

Not long after I arrived was the 12th of Tammuz, anniversary of the Previous Rebbe’s liberation from Soviet prison. In honor of the occasion, we all went to visit his resting place in Queens. Later, it became

known as “the Ohel,” but back then, there was only a gravestone.

In those days, the Rebbe would travel together with us on the bus to the cemetery. Once we arrived at the Ohel, there weren’t many people standing near the Rebbe, out of respect, but since I didn’t yet know how things worked, I ended up positioning myself right next to him. He was reciting the traditional Maaneh Lashon prayers, and so was I, and nobody told me to move away.

When he finished praying, while still holding his prayer book, he looked up at his predecessor’s gravestone and whispered something. I doubt any other bystander could have heard it, but I was standing so close to him that I did:

“Gut Yom Tov, Rebbe,” he said. Then he walked back a few steps and broke down sobbing.

The scene left a tremendous impression on me.

A few months after my arrival, I asked the principal of my yeshivah, Rabbi Mendel Tenenbaum, if I could go to speak with the Rebbe. He helped me set up an appointment for a private audience sometime after Simchat Torah. Because the Rebbe had not yet officially assumed the position, this first meeting was somewhat informal.

The Rebbe listened attentively to my broken Yiddish. The period after my arrival from Brazil was a difficult one for me, and I spoke about some personal things that had been bothering me as I was adjusting to being in yeshivah so far from home.

“Do you have a picture of the Rebbe?” he asked at the end of the conversation, referring to the Previous Rebbe.

When I replied that I did, he said, “You should keep the picture with you in your pocket or wallet, and look at it from time to time.”

I began to keep a picture of the Previous Rebbe with me, but later, when I became a little wiser, I began carrying an additional picture around – of the Rebbe himself.

He also told me to study one chapter of Psalms a day. “If you need, the yeshivah can give you a Psalms in Spanish to make it easier,” he offered – my Spanish was better than my Hebrew. “But use whatever means you can to learn a chapter a day.” The language in some chapters is not easy to understand, but I managed to do it.

This was, of course, apart from the regular, daily portion of Psalms that we recite as part of a monthly cycle.

Later, on a separate occasion, the Rebbe gave me an interesting directive regarding my daily studies. This time, it was about the daily Psalms, as well as the daily Tanya, the seminal work of Chabad philosophy that is divided according to an annual study cycle.

I had told the Rebbe about some personal matters in a private audience, and then he said to me: “Every day you should recite that day’s portion of Psalms as well as one chapter from tomorrow’s. And study that day’s Tanya, as well as tomorrow’s. And may G-d help you, that you should be today what others are tomorrow.”

One Shabbat shortly thereafter, I went to a farbrengen led by the Rebbe. The Previous Rebbe had told him to lead these chasidic gatherings once a month, but back then, before the official succession, there weren’t too many people present. It was just the Rebbe, sitting at the head of two tables that had been put together, a few men seated at the sides, and some yeshivah students around them.

I stood there, observing the Rebbe, listening, and trying to pick up whatever I could, even though the Hebrew and Aramaic terms he was using, and even some of the Yiddish, were above me.

At one point between talks, to my surprise, the Rebbe turned to me and said, “Maybe Herson can say l’chaim?”

Somebody poured me some wine, and I said “L’chaim!” In that moment, I started to feel a sense of hiskashrus, that I was connected and had a real relationship with the Rebbe.

Keeping a picture of the Rebbe with me – even a mental image – is something that stayed with me after I grew up and became an emissary of his. Several times a day, especially if I’m unsure how to proceed with some problem, I might take a break to think of the Rebbe’s holy image, so that I remember whom I am representing.

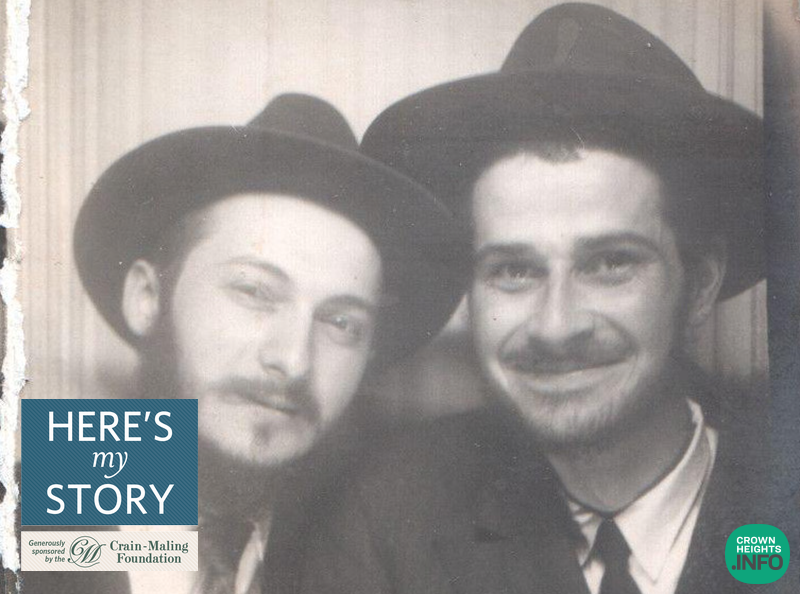

Rabbi Moshe Herson was the long-time regional director of Chabad of New Jersey. He was interviewed in May 2008 and November 2016, and passed away earlier this year.