The Life and Mission of Sholom Lipskar, the Miami Rabbi Who Never Stopped Working

by Dovid Margolin – chabad.org

Sholom DovBer Lipskar was in many ways a baby boomer, a child of the post-war generation that would change everything. He too had a sort of wild drive to upend this imperfect world. Like the most successful of his contemporaries, he was also blessed with a keen intellect, explosive energy and magnetic charisma. Unlike those whose zeal for a better tomorrow led them to reject the essential mores and bonds that had sustained humanity, Lipskar channeled his passions in a different direction: He joined the revolution being led by the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, to reveal the world’s higher purpose and empower every human being to find their unique role in it.

He got his start in 1969, when the Rebbe sent him and his wife, Chani, to Miami. Over the course of the next half a century, he would help galvanize a spiritual counter-culture.

“Miami,” the Rebbe wrote in a letter dating from 1973, “is a showcase for American Jewry from all parts of the U.S.A. … Every accomplishment there, in the area of Torah education and revival of Yiddishkeit, has the significance of a ‘pilot’ project for others to emulate.” In that icon of material success—and excess—the Rebbe saw the potential for a pioneering spiritual revolution that would help transform the landscape of American Jewry and trigger positive “repercussions on a global scale.”1

Lipskar, who passed away on May 3 (5 Iyar) at the age of 78, would be a conduit to help bring this potential into reality. He spearheaded construction of Chabad-Lubavitch of Florida’s first educational center and campus, and founded the first-ever yeshivah of higher learning in the southern United States. Then, in 1981, he moved north, to the ritzy and at the time waspy town of Bal Harbour, a beach community to which Jews were slowly moving but which had no synagogue. There he and his wife opened a place called simply, “The Shul.”

Today, The Shul of Bal Harbour sprawls over some 125,000 square feet on Collins Avenue in neighboring Surfside, and serves as spiritual home to hundreds of multi-generational families. While the area was once less-than friendly to Jews, the Lipskars and their Shul transformed Bal Harbour, Surfside and Bay Harbor Islands into a thriving, bustling Jewish community, a “showcase” to emulate. In many ways, these neighborhoods today form the gravitational center of Jewish life in South Florida.

“Bal Harbour, Surfside, Bay Harbor, they are what they are because of Rabbi Lipskar,” says Moshe Tabacinic, who first met Lipskar in Colombia in the 1970s. An investor and philanthropist, he has lived in Bal Harbour with his wife, Lillian, for 25 years. “I’m not even talking only about the Jewish community here; I mean in general. Everything that has been built here since he came was built upon his shoulders. He was the one who triggered all of it.”

In recognition of his stature, the towns of Bal Harbour and Surfside, which today are about 50 percent Jewish, flew their flags at half mast during Lipskar’s week of shiva.

George Rohr’s parents, Sami and Charlotte Rohr, first met Lipskar in the late 1970s as frequent visitors to Miami when they were living in Colombia. They moved to Bal Harbour in the early 1980s, where they became key supporters of Lipskar’s shul. “Early on, Rabbi Lipskar shared with my father the blessing he had received from the Rebbe, as well as the Rebbe’s perspective that Miami would become the gateway to much of South American Jewry and a very important center of Jewish life in America. He said all this long before it was,” says Rohr.

It wasn’t just The Shul that the Rohrs ended up supporting but a huge swath of Chabad-Lubavitch’s work around the world, from the former Soviet Union to college campuses across the United States. “Rabbi Lipskar was instrumental in making the shidduch between our family and Chabad,” says Rohr.

Mindful of the Rebbe’s call to pursue change on a “global scale,” the same year Lipskar started working in Bal Harbour he founded a national organization to provide spiritual and material support for Jews in the prison system and for those serving in the military. Since 1981, the Aleph Institute has grown into the largest Jewish organization caring for the incarcerated and their families. Founded upon the Rebbe’s teachings on criminal justice, it pioneered the field of alternative sentencing and provided the expertise and institutional knowledge crucial in the drafting and passage of the landmark First Step Act in 2018. Aleph actively promotes the Rebbe’s essential idea, too often lost in the conversation about crime and punishment, that every human being contains a Divine spark and has a singular role to play in the world. Its military division is one of two in the country to endorse Jewish military chaplains, and champions the unique needs of Jewish personnel in the U.S. Armed Forces.

Lipskar’s visible accomplishments have been widely hailed, and his passing drew condolences from Prime Minister Benjamin and Sarah Netanyahu of Israel, President Javier Milei of Argentina, the governor of Florida, U.S. senators and many other officials. According to those who knew him best, however, the truest testament to his life’s work is what cannot be seen on the surface.

“People will speak about The Shul, Aleph, and all the great things that he did, because those are the monuments that you can physically see,” says Tabacinic. “But if you could see what he has changed on the inside of so many people, that transformation is ten times more. That’s the greatness that he had.”

To the rabbi, these were two sides of the same coin. The most beautiful edifice was worthless without a soul. Speaking to the Miami Herald in 1993, on the cusp of his regal new Shul’s ribbon cutting, Lipskar described the project as a different kind of memorial to the tragedies of Jewish history.

“There was a tremendous interest in America for creating Holocaust monuments,” he said. “My feeling was that memorials by themselves are very temporary and after a few generations lose their impact. The way to meaningfully memorialize and honor the victims and martyrs of that period is to rebuild that which was destroyed, to bring to life again that which was razed and burned and plundered.”2

“It’s true he was the founder of the whole neighborhood,” says an emotional Jana Falic, a Bal Harbour resident who together with her husband, Simon, has known the Lipskars for 40 years. “But he was also the founder of our whole lives.”

Smuggled in a Suitcase

Sholom DovBer Lipskar was born on 4 Menachem Av, 5706 (August 1, 1946), in Tashkent, Soviet Uzbekistan, the second of Rabbi Eliyahu Akiva and Rochel Baila Lipskar’s five children.3 This was the era of the Great Escape, when the Chabad Chassidic community took advantage of the repatriation of war-time Polish refugees back to Poland to flee the Soviet Union—an evil empire which had been brutally persecuting Judaism from the dawn of its existence. By using forged and falsified identity papers to pass themselves off as Poles, approximately 1,200 Chassidim made it through the Iron Curtain to freedom.

While the Lipskars had succeeded in obtaining paperwork and train tickets for their family, they had neither for their newborn baby. Rather than wait and risk losing their chance of reaching freedom, the family chose to board the train from Lvov (today Lviv) crossing into Poland anyway. The 20-day-old Sholom was stashed into a suitcase with holes popped into its sides and carried out by his maternal grandfather, R’ Zalman Duchman. Once safely out of the USSR, they continued their travels through Poland—Lipskar’s father continuously bribing officials to ignore the fact that none of the Russian Chassidim spoke a word of Polish—until reaching Czechoslovakia.

Rebbetzin Chana Schneerson, the Rebbe’s mother, traveled aboard the same transport out of the Soviet Union, and the Lipskars were among those who assisted her during the difficult journey, parting ways once they’d reached Germany. Sholom’s earliest childhood memories were formed in the Schwabisch Hall and Feldafing Displaced Persons camps, where the Lipskars lived until emigrating to Toronto, Canada, in 1951.

Lipskar’s first teacher had been a Chassidic melamed back in the DP camps. In Toronto he studied at the Eitz Chaim yeshivah, transferring at the age of 15 to the Lubavitcher yeshivah in Brooklyn. At the end of 1963 Lipskar joined the higher yeshivah located in the Rebbe’s synagogue at 770 Eastern Parkway, where he excelled in his studies. He immersed himself in the environment, becoming a dedicated student of the Rebbe’s teachings and mode of thinking.

“As you observe the Rebbe, you are challenged and charged to perceive the world in a different way,” he would later explain. “You start seeing the physical world in the way that it was intended—to serve man instead of man serving it. Instead of working to achieve a materialistic goal, you start looking at how the materialistic aspects of the world are there to allow man to reach a higher-level goal. It’s a refreshing perception of the world. It challenges us. It’s futuristic.”

Lipskar often shared a memory from his first private audience with the Rebbe, when he was 9 years old. The Rebbe asked each of the children what they were studying. When Sholom’s turn came, the boy told the Rebbe he’d recently committed to memory a portion of Hamafkid, the third chapter in Tractate Bava Metzia. The Rebbe asked him to say it. “I recited the entire [two and a half pages],” Lipskar told Chassidishe Derher magazine in 2020. “It took several minutes, and the Rebbe listened to me closely the entire time.” That the Rebbe, a world leader whose every moment was so precious, had taken the time to focus so intently on a nine year-old boy’s studies would be a defining lesson for life.

This would hardly be the last time the Rebbe paid close attention to Lipskar’s progress and needs. From the start, Lipskar’s relationship with the Rebbe was marked by a deep, effusive Chassidic love—a love and dedication that animated his life’s work until the end, and one that he passionately articulated with everyone he encountered.

Pillars and Foundations

At the end of 1968 Sholom met and married Chani Minkowicz and, at the Rebbe’s instruction, spent the next year studying Torah in kollel. From the beginning, the couple expressed their desire to be sent on shlichut and join the slowly growing ranks of the Rebbe’s army on the frontlines of Jewish life. The Rebbe chose for them Miami and as Rosh Hashanah 1969 approached, the young couple set off for their new home.

At their final private audience before departing, Chani Lipskar shared with the Rebbe that while she was dedicated to the mission, she feared leaving behind her family and friends, and was worried she might not be up to the job. The Rebbe looked at her and smiled. “Ich fohr doch mit eich!” he exclaimed, “but I am traveling with you!” With that, Chani Lipskar’s fear dissipated. Then the Rebbe added a personal request, “It should be with joy!”

“Looking back, there is no way to explain [the success of our work here despite the many obstacles] if not for the fact that the Rebbe came along with us, quite literally,” Rabbi Lipskar said. “This was something we experienced at every step of the way.”4

His first position was as dean and principal of what was called at the time the Oholei Torah Day School in Miami Beach, started three years earlier by the regional director of Chabad-Lubavitch of Florida, Rabbi Avraham Korf. Lipskar hit the ground running. In a January 31, 1970 Miami Herald article titled ‘Generation Gap Begins in School: Parents Too Modern for Students,’ the 24-year-old Lipskar declared that the modern American Jews sending their children to Chabad’s Orthodox day school were returning to their heritage through their children. The children’s daily exposure to authentic Jewish practice in school, Lipskar reported, is causing “an awakening on the part of many parents when they realize their children care about tradition and religious observance.” He predicted the school would double in size by the following year.

Seemingly unable to do things the way they’d always been done, Lipskar was always innovating. Early on he launched a program in which the day school’s children would spend Shabbat at the home of one of their teachers, giving them the opportunity to not only learn about Jewish life in school, but experience it in action. One parent, Sheila Elbaz, described herself to the Herald as “a plain old Jew,” nearly an atheist. But something changed after her two sons spent Shabbat in the Chabad community. “They’ve been talking about the food and [the] kiddush. We’re going to try it at home,” she said. “We’re also going to try the Friday night walks [to synagogue].”5

By the end of 1970, Oholei Torah had outgrown its home and was renting space in the empty education building of a Miami Beach synagogue. Around then Lipskar met a self-made Miami millionaire named Mel Landow. Lipskar had started a Tuesday evening Torah class—this class went through various iterations, and by the early 1990s was still making headlines and drawing as many as 800 people—which attracted a local tennis champion. The player mentioned to the rabbi that he had a regular game with Landow, a major local appliance retailer. “I would like to put on tefillin with him,” Lipskar said immediately.

A meeting was arranged at the tennis club, but Landow declined the tefillin offer. So the rabbi made a bet with him: If their mutual friend beat Landow in their next set, Landow would put on tefillin. Landow agreed, lost the game, and headed out to Lipskar’s car to make good on his bet. Something about the encounter touched Landow very deeply, and though he told Lipskar he did not want to be asked about tefillin again, he joined the Tuesday night class.

Money had never been easy, and as the school grew—by now it had about 200 children—so did its debt. During a particularly difficult period in 1972, Landow called Lipskar and told him he was taking his company public and wanted to donate $500,000 for the construction of a new educational campus for Chabad. “Back then, such a large sum was unheard of, and it was only the beginning of Mel Landow’s involvement,” Lipskar told JEM’s My Encounter with the Rebbe oral history project. “I called the Rebbe[‘s office] right away to give over the good news.”6

A few days later Lipskar received a call from the Rebbe’s chief of staff, Rabbi Chaim Mordechai Aizik Hodakov, telling him it would be a good idea to put on tefillin with Mordechai Shoel, a.k.a. Mel Landow. The young rabbi began explaining to Hodakov that this was a very difficult thing to do. Then he heard the Rebbe’s voice on the line. “I jumped out of my chair,” he recalled. The Rebbe proceeded to say that he was going to pray at the Ohel, the resting place of his father-in-law and predecessor as Lubavitcher Rebbe, and it was an opportune time for Landow to put on tefillin. The Rebbe emphasized that the tefillin Lipskar was to offer Landow should be visibly beautiful, down to their external cases. Hodakov then told Lipskar to report back on what had transpired.

Landow was playing tennis when Lipskar pulled up. It was his biggest donor, the man who’d thrown Lipskar’s school not only a lifeline, but the opportunity to expand to new heights. He’d also explicitly told him never to ask him to don tefillin again. It’s not that Lipskar wasn’t afraid. He was, but the Rebbe’s instructions were uncontestable to him. “I already told you, it’s not my thing,” Landow told him. “But today is a very important day,” Lipskar responded. “The Rebbe is going to the resting place of his saintly father-in-law … to say special prayers, and if you would put on tefillin, I’ll let him know.” Suddenly everything changed. Landow agreed to put on tefillin.

Lipskar rushed to call the Rebbe’s secretariat. The Rebbe was already praying at the Ohel, and when Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky entered to relay the update that Landow had put on tefillin, the Rebbe smiled broadly. A few days later the Rebbe gifted Landow a brand-new pair of tefillin. Landow prayed with them every weekday for the rest of his life.

About a year later, Landow met the Rebbe in person for the first time. The meeting did not go exactly as Landow had anticipated, with the Rebbe pushing back on his plan to build a health center and tennis club in Israel, suggesting that he invest in education instead. The next day, the Rebbe’s secretary shared with Lipskar what the Rebbe had said about Landow (translation from Yiddish): “I met a person last night that the Almighty G‑d gave him merits that even I don’t have. Almighty G‑d gave him the merit to open the spigots, the faucets through which he will bring back 100,000 children to the Jewish faith. The foundations of buildings are not what you see, but the foundations,” he said, referring to Landow, “are what hold up the pillars.”7

The $2.2 million Landow Yeshiva Center on Alton Road in Miami Beach opened its doors in 1974, enrollment in the school having reached 300 children.8 That year, too, Yeshiva Gedola of Miami Beach opened its doors, the first such institution south of Baltimore. The Rebbe dispatched 11 rabbinical students from New York to form its founding cohort. Their main mission in Miami would be to study Torah, mentor the students of Landow Yeshiva, and utilize every free moment to share the warmth of Judaism with those around them. “We expect to change the face of Miami Beach and make it a spiritual haven,” Lipskar declared.9

‘We’re Becoming Kosher!’

Avraham Moshe Deitsch was one of the 11 Chabad students sent to Miami for a two-year stint at the new yeshivah. Chabad-Lubavitch of Florida was flying high. After years of debt, Lipskar had a primary financial backer. They’d built a gleaming Jewish educational campus in Miami Beach, something most people had said was impossible.10 Whatever Lipskar touched, it seemed, turned to gold. “He was an absolute powerhouse, and was amazing with people,” Deitsch recalls.

As the Rebbe had instructed, the yeshivah students studied during the week and used their free time to reach out to non-affiliated Jews. In the summer they split up into groups, some visiting towns up and down the state of Florida in a Mitzvah Tank, while others headed for Mexico, Panama, Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela and Colombia as part of a program Lipskar dubbed the “Trans American Jewish Peace Corps.”11

Deitsch recalls one afternoon spent putting on tefillin with Jewish students as they exited a school in North Miami, when he met a Jewish teenager named Kenny Shuster. They connected, and soon enough Kenny was spending more and more of his time at Landow Yeshiva, where he became known by his Jewish name, Yitzchak. Kenny began to wear a kippah, then tzitzit, and before his parents could get a word in, he was insisting to his mother that he could no longer eat at home as it wasn’t kosher.

“That’s when things exploded in our house, my mother having yelling matches with my brother” says his sister, Shirley Greenbaum. Their father, Dr. Marvin Shuster, was a successful plastic surgeon who lived with his wife, Susan, and three children in a sprawling lakeside mansion in Hollywood. The two-acre property boasted an Olympic-sized pool, a 20-car garage with a Rolls Royce, and a five-bedroom guest house. Though few other Jews lived in the area at the time, they were okay with that. “They were ‘cardiac Jews,’” Greenbaum says. No son of theirs would be joining a “Chassidic cult.”

One Friday, after Kenny had yet again skipped school and gone to Landow instead, the Shusters stormed down to Miami Beach to pull their son out once and for all. They arrived in yeshivah, but most of the young rabbis were out doing what the Shusters deemed “missionary activities.” Besides, at Landow they knew a Yitzchak Shuster, but no one had ever heard of Kenny. “That’s when they really freaked out,” recalls Greenbaum. A yeshivah student directed the livid Shusters to the Lipskar home on Pine Street Drive.

It was erev Shabbat, a busy time in any Jewish household, certainly at the Lipskars’. They were also confused why the young, supposedly Orthodox rabbi kept calling his wife “honey.” Lipskar calmed them down and made up to meet them at their home with his wife (Chani—not Honey) the next evening, Saturday night. He would explain everything to them.

“All I know is I woke up Sunday morning and my mother is saying ‘We’re becoming kosher!,’” recalls Greenbaum. “Sholom and Chani spent a few hours with my parents, and somehow conveyed to them the importance of kosher.”

When the Shusters made their decision, Lipskar said they would together relay all this to the Rebbe in New York. The Rebbe responded enthusiastically, stating that it would be worthwhile to make a big event out of the koshering of their home. Susan Shuster went all in. She had formal invitations printed and mailed, including one to the mayor of Hollywood. Their entire social circle showed up for the koshering day, an incongruous mix of Miami Jews and non-Jews in bell bottoms and loud shirts and Chassidic rabbis and yeshivah students in black hats. A chef in a tall white toque prepared the pool-side spread. The yeshivah students danced, schlepping white-pantsed and kippahed Miami natives into the circle and onto their shoulders. Lipskar at one point tried his hand jamming on the band’s electric guitar.

Shirley Greenbaum says that it was just the beginning of her family’s Jewish journey. Soon her mother was covering her hair, and her father praying with a minyan on Shabbat, when their guest house was transformed into the neighborhood’s first synagogue. As the Shusters’ responsibilities to their fellow Jews grew, so too did the Rebbe’s expectations of them. “Your husband is a plastic surgeon; he makes people beautiful on the outside,” the Rebbe told Susan during a private audience. “It should be your mission to make people beautiful on the inside.” Lipskar suggested to Shuster that she start sending a letter every month to the Rebbe detailing the people who’d come to their home and they’d positively influenced in their Judaism.

The guest house was soon too small for the synagogue, and the Shusters purchased a home in nearby Hallandale for the project. The synagogue, Congregation Levi Yitzchak, was named for the Rebbe’s father. In 1980 Rabbi Raphael (“Rafi”) and Goldie Tennenhaus arrived to establish Chabad of South Broward, taking over leadership of the Shusters’ synagogue.12

Greenbaum’s parents later moved to the Bal Harbour/Surfside area, where her mother still lives, maintaining a relationship with the Lipskars that continues to this day. “There’s a hole in my heart now,” says Greenbaum. “He was our spiritual father, my children and grandchildren’s spiritual grandfather.”

The Colombian Connection: A Marrano in the Country Club

Mel Landow’s appliance company went bankrupt in 1976. Difficult years lay ahead for Lipskar and the enterprise he’d been so instrumental in building. There were days, Chani Lipskar recalled, when she’d wake up praying the electricity in her home was still on. Rabbis and teachers who’d joined the burgeoning yeshivah staff started going without paychecks, sometimes for months straight. All of them struggled to put food on their table.

Lipskar soldiered on. “The Lubavitcher Rebbe tells us if we must choose between a child and the budget, we must always choose the child. It is easier to pay a late bill than to reclaim a child lost to Judaism,” he declared to the Herald in March 1977. “Who are we to tell a parent your child can’t be a part of Judaism because you don’t have enough money.”13

These weren’t just words, and his conviction took him to amazing places. Like the time in 1976 when he flew down to Barranquilla, Colombia, ostensibly to raise money for the Landow Yeshiva tuition of a Jewish boy from the city. Lipskar was greeted at the airport by the head of the Jewish community, Moshe Pancer. One of the first things the 30-year-old rabbi did was request a tour of the city’s two Jewish cemeteries. He later explained that one of the best ways to evaluate a Jewish community is to see how it cares for its dead.

At the Sephardic cemetery Lipskar saw a series of old gravestones, including one bearing the same name as the Colombian aviation hero the city’s airport is named for. The community representative explained that these were the graves of Jews who’d come from Curacao in the 1800s and their families were no longer part of the Jewish community—or even the faith. There was a prominent scion of one of these families, they told him, whose mother was Jewish, but had married out and attended church regularly. “Take me to see him,” Lipskar insisted. The man said he had no interest in either the rabbi or the Jews, but if this Miami rabbi really wanted, he could find him in his country club. Naturally, it was a club that banned Jews.

Necks turned as the black-hatted Lipskar walked through the club. The man told Lipskar he was no longer Jewish. “Why did you stop?” the rabbi asked him. “Wait, don’t worry, all Jews will stop eventually, just like me,” the man yelled back. He then pointed at another wealthy gentleman sitting in the next club chair. “See him, he used to be Jewish too!” He continued to berate Lipskar, who remained totally unfazed.

“I really respect you,” Lipskar said when the man was through, “you have a lot of guts. Fifty generations of your ancestors before you felt that keeping Judaism was important—you need to have a lot of guts after all that to come up with something new.” With that he walked out.

The next day the Jewish man from the club called on the young rabbi. They had a long conversation that ended with the man sobbing as Lipskar helped him don tefillin for the first time in his life. Like a Marrano of old, the man proceeded to pray in tefillin in a secret corner of his Barranquilla home for many years to come.

As far as Barranquilla was concerned, however, the “Marrano” in the country club was just the beginning.

Moshe Tabacinic’s older brother, Jose, was 30 years old and running his father’s schmatte business at the time of Lipskar’s arrival. Not unused to visiting rabbis collecting funds, and not particularly interested in getting trapped in a prolonged conversation which might end up costing him more money than he was inclined to give, Tabacinic had his donation prepared for Lipskar when Pancer—the head of the community and his father-in-law—introduced the two. “I gave him my check and he says: ‘N-n-n-no! I want to know, did you put on tefillin today?’” recalls Jose. “And I said, ‘Put on what?!?’ Before I could finish saying ‘what,’ my left arm was already wrapped up … .”

Tabacinic recited the Shema prayer wearing the tefillin and they started talking. “Do you have friends like you?,” the rabbi asked him.

“What do you mean, ‘like me?’”

“Like you, people who don’t put on tefillin.”

“Of course, all my friends in Barranquilla are like that!”

Lipskar asked the young businessman to host a gathering of his local Jewish friends that evening. “We got together a group of 10 people, and he came, and he started talking about Yiddishkeit,” Jose recounts. “You know how he was—he was amazing, how he spoke. He even brought kosher food with him.” Slicing open the kosher salami he’d flown to Barranquilla with, Lipskar said: “Let me show you how kosher food tastes!” Between the talk, the food, and perhaps a l’chaim or two, the crowd was mesmerized.

After that, Lipskar kept coming back, for a time flying down once a month to give a Torah class. Sometimes Chani would come with him and give a class to the Jewish women of Barranquilla. It was on one of Lipskar’s subsequent visits that Jose’s younger brother, Moshe, first met him in his brother’s house. “I was not interested in any rabbi, and of course he asked me to put on tefillin,” Tabacinic remembers. “I refused.” He adds, with a laugh: “Not long ago he reminded me, ‘There were very few people at that time whom I could not convince to put on tefillin!’”

While Judaism was important to the Jews of Barranquilla, Moshe Tabacinic explains, the way most of them expressed it was through support of Israel and community life. Torah and mitzvah observance was secondary. At the same time, their perception of religious people was more or less a negative one. “Rabbi Lipskar changed all of that,” he says. “People there began to look at Yiddishkeit completely differently.”

He was able to brilliantly convey the Torah’s eternal wisdom and insight, and especially its relevance to modern life. And it was not just what he said, but the sense of immediacy with which he conveyed it. “Sholom did not walk, he would run from one place to another,” says Jose.

This deep connection with the Jews of Colombia never fizzled, and helps to illustrate how many of the seemingly unrelated seeds planted by Lipskar in those years while doing the Rebbe’s bidding bore additional fruit years later, altering future generations. Members of the tight-knit Colombian Jewish community were already spending time in Miami in the 1970s, and as the country’s political situation disintegrated in the early ‘80s, they began immigrating to the area. Bal Harbour and Surfside were at the time under construction, brand new condo developments going up along the beachfront. “A lot of the people who later founded The Shul of Bal Harbour are from the original people in Colombia,” explains Moshe Tabacinic. “He not only influenced them, but their children as well, and then the next generations.”

One deep relationship Lipskar formed during that time in Colombia was with the Gilinski brothers—Max, Isaac and Lazar. On Lipskar’s visits to Barranquilla they’d stay up with the rabbi deep into the night, studying Torah and discussing the deepest questions in life. They’d never seen someone so passionately dedicated to Jewish education, a person who wasn’t paying lip service but seemed to care with every fiber of his being—and so young. Lipskar told them he was merely a messenger of the Rebbe; it was the Rebbe who cared for every Jew. He had tasked Lipskar with running a school in Miami, reaching out to Jews in Latin America, and a whole lot more. The brothers must meet the Rebbe, he said, he’d bring them himself. On one of their first visits, the Rebbe spoke about Miami and the Jewish work that needed to be done there, telling them they’d soon be living there. The Gilinskis were surprised. They had no plans of leaving Colombia, where the family had done very well for itself. Though they continue to maintain a relationship with Colombia—Lazar was the country’s ambassador to Israel in the 1980s, and Isaac from 2010-2013—the family is based in Miami, Bal Harbour to be precise.

Moshe Pancer, the once-head of Barranquilla’s Jewish community, likewise moved to Bal Harbour and ended up serving as a president of The Shul. His daughter Miriam and son-in-law Jose Tabicinic moved to Miami as well. Sometime after their arrival, in 1983, Jose and Miriam divorced. It was Lipskar who succeeded in reuniting the couple, and in 1986—after three years apart—they remarried in the Lipskar home. Their children and grandchildren have likewise been a part of the Lipskars’ activities in one way or another. Similar multi-generational and multi-dimensional stories appear in family after family touched by Lipskar at various junctures in his life.

Miriam clarifies that it was not his fundraising trip that had launched their community’s relationship with him, but something else entirely. “Way before 1976 my father went to New York and met with the Rebbe, and told him we need help finding a rabbi for Barranquilla,” she says. “The Rebbe told my father: Go to Sholom Lipskar in Miami, he’s going to help you. That was our first contact with him.”14

Pillars, the Rebbe had explained, rest upon unseen foundations.

Crisis and Rebirth

By the end of 1979, the pressure was taking its toll on Lipskar. As he battled one emergency after another, relationships with both creditors and personnel suffered, leading to disagreement about the Landow Yeshiva-Lubavitch Educational Center’s path forward. For a time, Lipskar entertained leaving Miami to pursue Chabad work with university students in the Northeast. The Rebbe did not reject the idea outright, saying that while he preferred for him to remain in Miami, it was Lipskar’s choice to make. Upon hearing the Rebbe’s preference, he stayed.

The question was what Lipskar should focus on. The Rebbe granted him a year’s “leave of absence,” later extending it to a year and a half. He spent the time studying, thinking, writing and lecturing in the United States and abroad. A benefactor also sponsored him to attend every one of the Rebbe’s farbrengen gatherings in person, and he’d fly into New York for those occasions from wherever he was in the world.

It had been dedication to the Rebbe’s ideas and mission that had pulled him out of difficult times before. Back in 1972, Lipskar had been diagnosed with a heart murmur and underwent surgery. While the procedure had gone well, the situation quickly turned critical when Lipskar could not be woken up from the general anesthesia. Chani Lipskar frantically called the Rebbe’s secretariat to request the Rebbe’s immediate blessing. Rabbi Hodakov had taken the call, and asked her for a number to reach her at. A few minutes later he rang again. “I need to speak to your husband,” he told her. Chani responded that it was impossible—her husband was unresponsive. “Did you hear what I said?” Hodakov repeated. “I have directions from the Rebbe to speak to your husband. The Rebbe has a job for him.”

Overriding the nurses’ objections, Chani arranged for Hodakov to call the phone outside of Lipskar’s hospital room, pulling it inside and placing the receiver at her husband’s ear. The next thing the rabbi knew he heard Hodakov’s voice: “The Rebbe said that you should call the university in Winnipeg to organize a reception for Prof. Herman Branover when he visits there.” Lipskar could make out the Rebbe’s voice in the background as well. Branover was a noted Soviet Jewish scientist who’d become observant behind the Iron Curtain and had recently been granted permission to leave the USSR. Hodakov went on to say that from Canada Branover would come to Miami, where Lipskar should introduce him to people in his academic field.15

The fact that the Rebbe had a job for him to fulfill had literally revived him. Branover did indeed come to Miami to lecture, and his relationship with Lipskar would later also birth the Miami International Torah and Science Conference.16

Just as dedication to the Rebbe’s work had restored him years earlier, so too would it now. After Passover 1981, Lipskar had a 46 minute private audience with the Rebbe—such audiences were rare following the Rebbe’s heart attack three years prior—during which the Rebbe gave Lipskar pivotal guidance for the future.

A short while later a Montreal developer named Sam Greenberg shared his plans for new construction in Bal Harbour with the Rebbe, who asked him why there was no synagogue yet in the town. Greenberg knew Lipskar from Miami Beach, and invited him to come to Bal Harbour. Lipskar in turn asked the Rebbe whether this was the right thing for him, receiving the answer “nachon ha’davar,” or “this is the correct choice.” Direction in hand, he was off.

Lipskar opened The Shul of Bal Harbour with little fanfare in December 1981, hosting services in a store on the basement-level shopping arcade of the Beau Rivage Hotel. It was small at first, the Lipskars coming up each week from Miami Beach and staying with their two small children in a motel, but the venture quickly expanded.

“There were very few Jews living in Bal Harbour at the time,” recalls George Rohr. In fact, as late as 1982 the oldest and nicest neighborhood in the village had active deed restrictions in place requiring properties not be sold to people “with more than one-fourth Hebrew or Syrian blood.”17 Meanwhile, the beach side of Collins Avenue was being developed, and it was to these large new condo buildings that Jews were moving, including Latin American Jews leaving the instability of their home countries.

The Rohrs initially rented in the area, purchasing their home only once it was clear that the Lipskars were becoming a vibrant presence in Bal Harbour. “Already then you could sense tremendous momentum,” he says. “My father would often speak admiringly about the creativity and force of personality that Rabbi Lipskar brought to bear building this community—he was thinking very big from the very beginning.”

Many of the Jews living in the area hadn’t been involved with their Judaism in any real way in decades—if ever. “I haven’t gone to Simchat Torah since I was a kid carrying a flag with an apple on it 60 years ago,” 69-year-old Saul Tabb told the Miami Herald at the time. “I’m not going to call it a miracle, but [Rabbi Lipskar] gave me the inspiration I was looking for. He gave me faith I can’t explain but that I just feel good about.”18 A year later, the Herald wrote about Harry Persky, an 82-year-old snowbird who hadn’t put on tefillin since before World War I. “My faith was not a daily practice,” he said. “Now it is.”19

“Every speech that he gave in The Shul, people were mesmerized,” recalls Moshe Tabacinic. “At that time the majority of the crowd was not actually observant, and The Shul that he eventually built was really created with his Baalei Teshuvah [returnees to Jewish practice.] He was able to give strength and reinforce the kernels of people’s Judaism, and nurture it to grow.”

“We moved to Bal Harbour in 1987 because of The Shul, because of the rabbi and the rebbetzin, and because we wanted to be a part of this community,” says Jana Falic. Following the familiar pattern, her family’s connection with Lipskar stretched back to the ‘70s, when Lipskar used to visit her husband Simon’s father at his little jewelry shop on 41st Street in Miami. When she got married in 1979, it was Lipskar who officiated.

“He was like a part of our family—you think I’m just saying that, but it’s true,” she says. “He married me, he named my children, he married my four children, and he named my grandchildren.”

Falic notes that Lipskar treated everyone with respect. “He was as good with a child as he was with the prime minister of Israel,” she says. He also never shied from pressing people to steadily advance in their personal mitzvah observance, whether laypeople or major donors. This was the path to a life of connection and meaning, he’d share from the Rebbe, the Jew’s connection to the Divine—it was for everyone.

“A big part of his connection with people lay in his ability to inspire everyone—regardless of age, background or profession—to recognize their own importance to the Jewish story,” explains Rohr. “He made you understand that you couldn’t just be a spectator; you were an essential partner in shaping the future of the Jewish people. Whether you were a donor, a teenager, or someone just beginning to explore your heritage, he empowered you to take ownership and responsibility. His message was clear: if you know aleph, you teach aleph. Everyone has something to give, and everyone is needed.”20

Between Lipskar’s speeches, classes, counseling—it was not unusual to see the cars of people he was counseling parked outside his home at 2 a.m.—and sheer passion for Judaism, The Shul kept growing. They rented space in a shoe store, then in the Sheraton, then a larger storefront, before breaking ground on their 80,000 square foot new building in 1991. Lipskar himself rammed a bulldozer into one of the old motels sitting on the property during the ceremony. The building was finished three years later, becoming not only a South Florida landmark, but breaking the mold of what a Chabad center could—and should—look like.

“At a critical time, Rabbi Lipskar modeled for his fellow Chabad emissaries what visionary leadership looks like,” Rohr continues. “He didn’t just dream big—he inspired others to dream with him, and he articulated those dreams in ways that felt natural and achievable to everyone: donors, community leaders, city officials, and beyond. Bal Harbour started with nothing. But one man’s tenacity, vision, and unwavering belief in people’s potential showed us all what could be accomplished. Rabbi Lipskar’s legacy is not just what he built, but how he empowered others to build alongside him.”

Long before the Gilinski family grew into financial partners in Lipskar’s work, he was their mentor, teacher and friend. That’s the way Lipskar formed relationships—it was about Torah and mitzvahs, not dollars and cents. “My priority was to learn with people and share Jewishness with them,” Lipskar shared of his approach. Fundraising can never be the goal, he explained. It is by connecting individuals with G‑d and His instructions for life, that they can also grow into partners—whether as donors, connectors, motivators or volunteers—a core aspect of Jewish life in and of itself. “… Programs came into existence as outgrowths of those relationships. People recognized that there were needs; they weren’t my needs or my agenda, they became a common agenda.” So it was with the Gilinskis, who sought to partner with Lipskar in strengthening Jewish life and education in their new hometown. When Lipskar was building The Shul in the early 1990s, they dedicated the synagogue’s sanctuary. More recently, the next generation of the family dedicated The Shul’s new youth building.

![“The way to meaningfully memorialize and honor the victims and martyrs of [the Holocaust] is to rebuild that which was destroyed, to bring to life again that which was razed and burned and plundered,” Lipskar told the papers. “The way to meaningfully memorialize and honor the victims and martyrs of [the Holocaust] is to rebuild that which was destroyed, to bring to life again that which was razed and burned and plundered,” Lipskar told the papers.](https://w2.chabad.org/media/images/1321/UybK13211012.PNG?_i=_nC373D4D4185A783403BE975A24EAD9F9)

During the construction of The Shul’s recent expansion, Lipskar asked the Gilinski family whether they wanted to dedicate the campus’s central structure in the family name. They demurred—it seemed too big of an honor to take. When Lipskar offered that they name the expansion in the Rebbe’s honor instead, they jumped at the opportunity, sponsoring the dedication that today carries the Rebbe’s name.

Emblematic of Lipskar’s standing in Bal Harbour and Surfside was the aftermath of the horrific 2021 Champlain Towers collapse. In the first days after the tragedy, The Shul community rushed to fill the center’s massive, soon-to-be-completed expansion with everything their displaced friends and neighbors and families of the missing needed. It became a hub of hope and relief for everyone. During that devastating time, it was to Lipskar’s steady spiritual leadership and moral voice that the broken community turned, both Jewish and not.

“We do not have it within our capacity to understand such a tragedy,” he said at the time. “The human mind does not have the ability to absorb something of this nature intellectually. The only thing that has any semblance of ability to communicate during this period of time is G‑dliness, is the neshama, the soul.”

The Aleph Institute: Lifting Society from its Lowest Point

What moved Lipskar and motivated him most was the Rebbe’s transformative vision for society and its profound philosophical underpinnings. The Rebbe, his boss ultimately, had suggested he remain in Miami, so he focused his energies on building a community in Bal Harbour. During the aforementioned 1981 private audience, Lipskar asked the Rebbe what else he should work on. “Der Aibershter vet dir gebn a machshava tovah,” the Rebbe responded, “G‑d Almighty will give you a good idea.”

As Lipskar recalled to Chabad.org in 2019, the following Shabbat he was at the Rebbe’s farbrengen gathering in New York when the Rebbe deviated from the subject he was addressing for a moment. “It’s an astonishing thing … People go and search for a Jew with whom to put on tefillin, and with whom to share the wisdom of Chassidus, which is a very good thing,” Lipskar recalled the Rebbe saying, in Yiddish. “Meanwhile, hundreds and thousands of Jews are sitting and waiting for someone to come and help them put on tefillin, or study Chassidus with them, and although we’ve spoken about this on numerous occasions, nothing [comprehensive] has been done about it. I am referring to Jews who are currently in prison.”

It dawned on Lipskar that he had his project. The very next morning he wrote to the Rebbe stating that pursuant to the “good idea” he’d said G‑d would give him, he was thinking of getting involved with Jewish prisoners. The Rebbe responded with an immediate blessing, and the Aleph Institute was born.

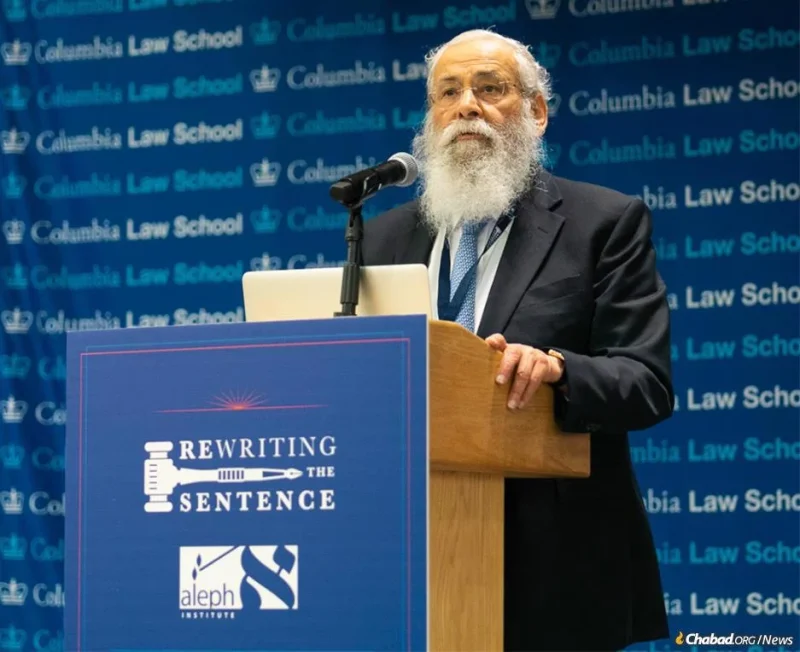

There were two central prongs to the idea, Lipskar explained in the 2019 interview, which took place as the Aleph Institute was holding its landmark Rewriting the Sentence summit on alternatives to incarceration at Columbia Law School:

The first was the Rebbe’s pure love for humanity. “He hurt when someone was hurting, it was that simple.” At the same time, Lipskar continued, “the Rebbe’s philosophical approach was that we have to repair the world to bring Moshiach, period. To fix the world. The Rebbe explained many times that when you need to lift a building you don’t lift it from the top, you put a lever on the bottom. When you lift the bottom the top gets lifted too. You have to deal with the people at the bottom of the totem pole. You judge a society not by how its best people fare but how you treat the most unfortunate.”

Lipskar had big ideas when he began, but the prison system is an alternate universe, one that can take years to break into. By an early stroke of Divine providence, someone mentioned to the rabbi that Judge Jack B. Weinstein, then the chief judge of the Eastern District of New York, might be a sympathetic ear. Lipskar made a cold call and set up a meeting.

During their initial conversation, Weinstein was heartened to learn that the Rebbe’s outlook on criminal justice closely mirrored his own. Over the next decade, Weinstein personally met the Rebbe as well, encounters whose impact would remain with him until the end of his long life. Lipskar credited Weinstein with putting the Aleph Institute on the map.

“Who was Aleph at that time? We didn’t have an office, it was just one person running around to prisons,” Lipskar recalled. Weinstein encouraged him in his work when they first met, telling him he was on the right track. “But nobody is going to listen to me,” Lipskar responded. Weinstein picked up the phone and dialed Norman Carlson, director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, and told him there was a young rabbi he wanted him to meet. “That changed everything. Because of that we were able to come in right at the top.”

In the beginning, Lipskar worked on the basics: even providing prisoners with access to religious materials and kosher food entailed uphill battles, with officials routinely denying such requests. He visited prison after prison to meet incarcerated Jews, teaching them and connecting with them. Within a few years of its launch Aleph was running yeshivah programs in prisons, and creating programming for federal prisoners granted furlow to immerse themselves in Torah study and prayer. On more than one such occasion Lipskar brought groups of prisoners to the Rebbe’s farbrengen.

As Aleph grew, so did its programs. There were family services, reentry training, preventative education and advocacy. It was a pioneer in alternative sentencing precisely because Lipskar knew from the Rebbe’s teachings that Torah by and large frowns upon incarceration as a mode of punishment. Even when prison is necessary, Lipskar explained in an essay, it cannot lose focus of its goal. “Our prison systems spend much time and money on vocational, academic and psychological programs,” he wrote. “To really accomplish the rehabilitation that is possible in prison, we should also focus on emancipating and structuring the soul—maximizing the human potential even while temporarily incarcerating the body.”

“[Rabbi Lipskar] stimulated me, helped me see who I am and lifted a weight off my shoulders,” a prisoner told the Miami Herald in 1984. “ … Your being, your soul, knowing who you are, is more important than any party you can go to.”21

Aleph’s military branch likewise grew. It was instrumental in the successful effort to get the military to lift its ban on beards for religious purposes, and currently endorses 45 active Jewish military chaplains. Today, it works with more than 3,500 Jewish military personnel on 600 bases in 30 countries.

‘A responsibility to the whole world’

The difference between his first career at Landow and his second life in Bal Harbour, Lipskar explained, was moving away from a reactive, emergency mode he felt he’d too often operated on to a proactive investment model—not soliciting donors, but partners. It also meant scaling properly and growing in a sustainable way. That did not mean he ever stopped working or dreaming of more. During his interview with Chabad.org in a cab between Weinstein’s Brooklyn chambers and Aleph’s summit in Morningside Heights, Lipskar grew most passionate not about the things he’d built and accomplished, but about the ones he still wanted to do. He’d once had a learning program, a school, really, for seniors called Torah Academy for Adult Jews—Kollel Tiferes Zekainim Levi Yitzchak. It was founded upon the Rebbe’s teachings that the elderly should not be cast aside, but instead be given the opportunity to study, find renewed focus in their lives and be enlisted to share their wisdom with society.22 It had been successful, but he’d been forced to cut it to focus on The Shul and Aleph. “It’s still on my planning board,” he said.

Lipskar’s lifelong motto was “over the top,” words he used to convey the Chassidic aphorism “l’chatchila ariber” that the Rebbe had written in a letter to him. There was no time to aim for mediocrity, only excellence. “That’s what the Rebbe taught us,” he said. “We have a responsibility to the whole world, that’s our job, that’s who we are.”

Lipskar is survived by his wife and life partner Chani; daughter Devorah Leah Andrusier; and son Rabbi Zalman Lipskar, who is continuing his father’s work as spiritual leader of The Shul of Bal Harbour and chairman of the Aleph Institute. He is also survived by many grandchildren, great-grandchildren, as well as the countless souls he touched across generations.

Footnotes

1. Letter from the Rebbe to Mordechai Shoel (Mel) Landow, 22 Adar II, 5733/March 26, 1973, available here. As will be detailed below, Landow and Lipskar had grown close by this time, and Landow’s name was already destined to grace the Lubavitch educational complex in Miami that Lipskar built. On Landow’s first occasion meeting the Rebbe, he detailed his plans to build a grand health and tennis club in Israel. The Rebbe rejected the idea, suggesting he instead invest in educational projects in Israel. After the meeting, the Rebbe wrote to Landow: “Frankly, I had wondered what your reactions might be to my ‘un-American’ manner of welcoming you. For, the accepted American way, if I am not mistaken, is to greet one with a shower of compliments and praise, even if not always fully merited. In your case, of course, it would have been very well deserved credit, for I was fully aware of your accomplishments and generosity in behalf of the Lubavitch work in your community, given in the best tradition of inspiration and dedication, even to the extent of getting your friends involved in it. Yet, instead of verbalizing my appreciation at length, I glossed over it briefly, and immediately challenged you with new and formidable projects.”

2. Peter Whoriskey, ‘Designing God’s House,” The Miami Herald, Oct. 16, 1993.

3. Some of the biographical details here are drawn from ‘“Ich For Doch Mit Eich:” An Interview with Rabbi Sholom Ber Lipskar,’ A Chassidishe Derher, Sivan 5780.

4. Derher.

5. Adon Taft, ‘Homework’ Revives Tradition,’ Miami Herald, March 20, 1970.

6. Jewish Educational Media (JEM) publishes one story from their interview archive each week in a pamphlet called “Here’s My Story.” ‘Game, Set, Wrap,’ in which Lipskar speaks about his early interactions with Landow, was released for Shabbat of Tazria-Metzora, 5785/2025, the day Lipskar passed away.

7. The Rebbe said these words in Yiddish, and Lipskar wrote them down at the time, Letters To My Father, (Miami, 2006), p. 11. For more context see above, fn. 1. Twenty-five of the Rebbe’s letters to Landow are accessible here.

8. Adon Taft, ‘Landow Yeshiva To Be Dedicated Sunday on Beach,’ Miami Herald, Sept. 6, 1974.

9. Adon Taft, ‘Eleven Youths Arrive in Dade To Start Rabbinical College,’ Miami Herald, Dec. 7, 1973.

10. One noted non-Chassidic pulpit rabbi who led a congregation in Miami Beach in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s reportedly said at the time, “hair will grow on my palms before a yeshiva succeeds in Miami Beach.”

11. Cathy Lynn Grossman, ‘Hasidic Students Reach Out To South American Jews, Miami Herald, July 11, 1975.

12. The last letter the Rebbe is known to have signed before suffering a stroke in 1992 was addressed to the annual dinner of this synagogue, Congregation Levi Yitzchak-Lubavitch of Hallandale.

13. Cathy Lynn Grossman, ‘Lubavitchers: Kosher All the Way,’ Miami Herald, March 13, 1977.

14. Rabbi Yehoshua Binyamin and Rivka Rosenfeld established Chabad of Colombia in the capital city of Bogota in 1980. (Rosenfeld had also been part of the first cohort of rabbinical students sent by the Rebbe to Yeshiva Gedola of Miami in 1974). Chabad of Barranquilla has been helmed by Rabbi Yossi and Chana Liberow since 1989. Today, there are also Chabad centers in San Andres, Salento, Cartagena, Cali and Medellin.

15. JEM’s Here’s My Story No. 533, ‘Time to Rise and Shine,’ March 31, 2023.

16. Branover lectured at the University of Miami and spent Purim 1973 in the city “at the invitation of Lubavitch Rabbi Sholom Lipskar.” Bob Wilcox, ‘Purim has special meaning for ex-Soviet professor,’ The Miami News, March 13, 1973.

17. Gelareh Asayesh, ‘Diversity moves in: Jewish families settle in Bal Harbour neighborhood,’ Miami Herald, Aug. 21, 1986.

18. Adon Taft, ‘Sukkah is a first for Jews in a new Bal Harbour Shul,’ Miami Herald, Oct. 8, 1982.

19. Laura Owens, ‘Growing congregation finding Jewishness at Bal Harbour shul,’ Jan. 13, 1983.

20. This included Rohr’s father, Sami, whom Lipskar encouraged to give a regular class on the weekly Torah portion. Rohr visited the Rebbe in 1991 to thank him for this.

21. Andres S. Viglucci, ‘Jewish inmates find their heritage,’ Miami Herald, Nov. 8, 1984.

22. “I don’t like to say it but I guess I was wasting my time,” 66-year-old retired postal worker Milton Helfgott told the Miami News of his life before joining Lipskar’s Kollel Tiferes Zekainim Levi Yitzchak in Miami Beach. “I was leading an empty life. [The learning] is always something I wanted to do but I never had the opportunity. This gives me more value in my life. It gives me a feeling of accomplishing something … it’s like rekindling the light of knowledge.” See Norma A. Orvitz, ‘Rekindling lights of faith,’ Miami News, Dec. 18, 1981.