Dr. Bernard Lown and the Rebbe’s Matzah

by Dovid Margolin – chabad.org

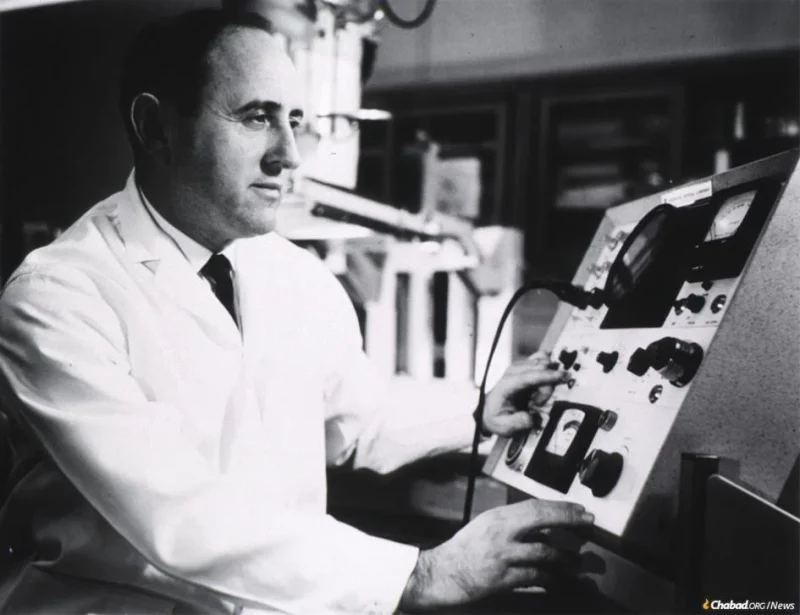

There are many reasons for the late cardiologist Dr. Bernard Lown’s fame, any one of which could have been a life’s achievement.

Born Baruch Latz in Lithuania in 1921, he immigrated to the United States with his family as a teenager, later going into medicine. Lown’s early research uncovered the link between potassium levels and the safe usage of the centuries-old heart failure drug, digitalis. His early investigation of the role that arrhythmia played in sudden cardiovascular death made him an expert in a subject not well understood by most in his field. At the time, Lown recognized that administering a well-timed shock to the heart could break dangerously abnormal rhythms and restore a normal heartbeat, leading to his 1962 development, together with engineer Baruch Berkovits, of the DC defibrillator and his creation of a device called a cardioverter. These advances not only saved many thousands of lives directly, but opened the doors for safer open-heart surgery and the development of the pacemaker. A few years later, he became the first to use Lidocaine to treat arrhythmias. In 1964, when he opened a coronary care unit at what is today Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, it was one of the first in the world.

Then comes perhaps his greatest contribution to cardiology, the “chair method” he developed together with his Harvard mentor, Dr. Samuel Levine. Beginning in the early 1950s, the two discovered that by seating patients with cardiovascular diseases in an armchair instead of lying them down on a bed allowed patients to breathe easier and their heart to recuperate. This simple observation, Lown later explained, “changed the whole course of cardiovascular care.” Though met by fierce resistance from the medical establishment of the time—bedrest was deemed an unquestionable part of hospital care—the chair method is in wide use today and has saved an immeasurable number of lives.

Lown’s expertise was regularly sought by world leaders, and among Lown’s patients were King Hussein of Jordan, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau of Canada and U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas.

Beginning in 1977 and continuing for some time after, the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, was a patient of his as well. How this happened is a whole other story, which can be read in detail here. Suffice it to say Lown was sitting in the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow, which he was visiting to treat high-ranking Kremlin officials, when he was called out to the phone. “Boruch!” shouted the caller in Yiddish. “The Lubavitcher Rebbe isn’t well, you must come to New York now!”

The man on the line was his Chassidic cousin, who explained that the Rebbe had suffered a heart attack on the holiday of Shemini Atzeret, and that Boruch, a.k.a. Bernie, a.k.a. Dr. Bernard Lown, must get on the next plane heading towards New York.

Lown arrived at the Rebbe’s office at 770 Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn to find a team of young, talented and energetic cardiologists already overseeing the Rebbe’s care, two of them, Dr. Ira Weiss and Dr. Louis Teichholz, his former students at Harvard. Lown did not restructure the systems they’d set in place, instead examining the Rebbe and offering advice from his vantage point as a senior doctor in the field.

The Rebbe’s heart attack took place in October 1977, and in the hours and days that followed Weiss, Teichholz and others set up a makeshift hospital room for the Rebbe at 770. Five weeks later, on Rosh Chodesh Kislev, the Rebbe returned home.

Nevertheless, the Rebbe’s cardiologists continued to monitor him. Aside from them, over the next year or so Lown would come to examine the Rebbe about once a month, decreasing in frequency in the years that followed.

The Shmurah Matzah

Every year on the eve of Passover, the Rebbe distributed shmurah matzah to individuals for use at their seders. Since the Rebbe’s matzah was baked that very morning and people tend to stick close to home on Passover, the distribution was mostly limited to those in the immediate New York City area—people who could receive the matzah and be back home in time for the holiday.

Passover 1978, the first after the Rebbe’s heart attack, was no different: The Rebbe stood outside his office distributing matzah to a line of supplicants. Towards the end of the distribution, about 4:30 or 5 in the afternoon, one of the Rebbe’s secretaries, Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky, asked for matzah for himself to use at his family’s seder that evening.

“I don’t know why, but when I went over, I also asked for a piece of matzah for Dr. Lown,” Rabbi Krinsky explained in a 2021 interview with Chabad.org. “The Rebbe looked at me, gave me a whole matzah, and asks ‘Will he get it before Pesach?’ What that told me was that no question, the Rebbe wants him to get it before Pesach.”

Passover was mere hours away. Krinsky packed up the matzah as quickly as he could, got hold of a yeshivah student and gave him cash for a cab. He then told him to rush to the Marine Terminal in Queens to catch someone boarding an Eastern Air Shuttle flight to Boston and ask them to take the package. During that more innocent era of air travel, Eastern ran an hourly shuttle service between New York and Boston which did not even require reservations. Then Krinsky rushed back into the office and called his brother in Boston, the late Rabbi Pinchas Krinsky, to inform him of the matzah on its way to Beantown.

Rabbi Pinchas Krinsky’s children remember that after his brother called him from the Rebbe’s secretariat, their father sped to the airport. It wasn’t just the eve of Passover, but also a Friday afternoon—erev Shabbat. The airport was mobbed with weekend travelers. He also had no idea who was bringing the Rebbe’s matzah from New York, not what he or she looked like—or even their name. As he stood in the terminal wondering how in the world he’d ever find the matzah-bearer, he suddenly saw a man coming down an escalator awkwardly holding a massive, plastic-wrapped box. He had his man—and the matzah. But Passover and Shabbat were dawning, and time was ticking away.

“My father said that the whole drive was miraculous,” recalled his son Rabbi Mendy Krinsky, director of Chabad of Needham, Mass. “Any road he took somehow was suddenly cleared of traffic, whichever way he turned everything opened up for him. It was amazing.”

Guided from Above, and taking advantage of his deep knowledge of Boston’s maddeningly winding roads, Rabbi Pinchas Krinsky sped from Logan to Chestnut Hill, where the Lowns lived, and then back to his own home in the Brighton neighborhood, arriving with just minutes to spare before the holiday.

“I remember the Rebbe was very pleased that it worked out,” Rabbi Yehuda Krinsky recalled. With the tradition now initiated by the Rebbe, every year from that point on Krinsky would send a box of shmurah matzah to the Lown residence. Other than that and mailing out the Rebbe’s periodic personal donations to Lown’s foundation, Krinsky didn’t have a whole lot more contact with Lown in the ensuing years. Unbeknownst to him, though, the matzah became an important part of the Lown family’s Jewish life.

Though Lown had studied in a yeshivah in the old country, the family “Americanized” in the New World, which many Jewish immigrants of the era took to mean dropping religion in totality. Bernard and his siblings were not raised religious at all. In fact, the only reason why his son Fred had a bar mitzvah and went to Hebrew school was because his grandfather was a big figure in a temple and insisted on it, not because of his father.

But there was something special about Passover.

“Every Pesach, a week before, we’d get a big box of shmurah matzah … from the Lubavitchers in Brooklyn,” Fred Lown told Chabad.org in 2021. “ … My mother would place it on one of her most beautiful pieces of china, wrapped in a gorgeous embroidered napkin, and the shmurah matzah would sit in the center of the table, at every seder.”

For Dr. Lown, it was not only the matzah that became a tradition, but recalling the man who sent it to him. “He spoke about the Rebbe often with family members and close friends, but every Passover, when the shmurah matzah was passed around, it was a story about the Rebbe,” Fred shared. “I remember that vividly from all the seders that I’ve attended … . [My parents] became the reigning patriarch and matriarch of our extended family, and the Rebbe and the shmurah matzah was a central part of it.”

Lown may not have been religious—he was perhaps even anti-religious—but over the course of a long life he communicated an unyielding belief in something higher. He did this in his approach to medicine, in the stories he told, and in the matzah he ate, a love for which he passed on to his children and grandchildren.

It’s not incidental that Lown, the healer, was drawn to the matzah, which the Zohar refers to as “the food of faith” and “food of healing.”

Matzah, the Rebbe explained on more than one occasion, represents the raw spark of faith found within the deepest recesses of the soul. By consuming matzah on the nights of Passover the Jewish soul reconnects with its Creator not on the intellectual or emotional plane but the essential one, where man and G‑d are one.

The Zohar refers to matzah first as the food of faith, and then as that of healing. The order is not random, but a prescription for the ultimate preventive medicine.

“On the first night [of Passover], matzah is ‘the bread of faith.’ On the second night, it is ‘the bread of healing,’” Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of the Chabad movement, explained. “When healing leads to faith, in that a person says, ‘I thank You, G‑d, for my recovery,’ he was, nevertheless, sick. But when faith generates healing, a person is not sick in the first place.”

It’s a vision of healing Dr. Lown well understood.

This article was adapted from “The Nature of Healing: The Rebbe and Nobel Prize Cardiologist Bernard Lown,” published on Chabad.org in 2021.