Weekly Story: The Farbrengen Continues

by Rabbi Sholom DovBer Avtzon

One of the basic teachings of Chassidus is, that when we communicate and celebrate a special occasion, it is pertinent not only for that day, but that day should influence our conduct from then on.

Therefore, this week, and b’ezras Hashem next week, I will be posting a few of the stories or anecdotes that I heard from various individuals at farbrengens recently on Yud Beis Tammuz as well as Gimmel Tammuz, which I believe the readers will enjoy.

As always, your comments and feedback are welcomed and appreciated.

Rabbi Moshe Raitport related the following:

Some years ago, on Simchas Torah, he was in a shul in Boro Park and an elderly respected individual noticed him and seeing that he is a Lubavitcher chossid, came over to him.

He said, “I am going to relate to you a story, however, you are not to ask me questions about it.”

Moshe said, “I don’t know if I can agree to that condition”; however, that person started to speak with tears flowing down his beard. It was evident that he was becoming extremely emotional, as if he was reliving an experience.

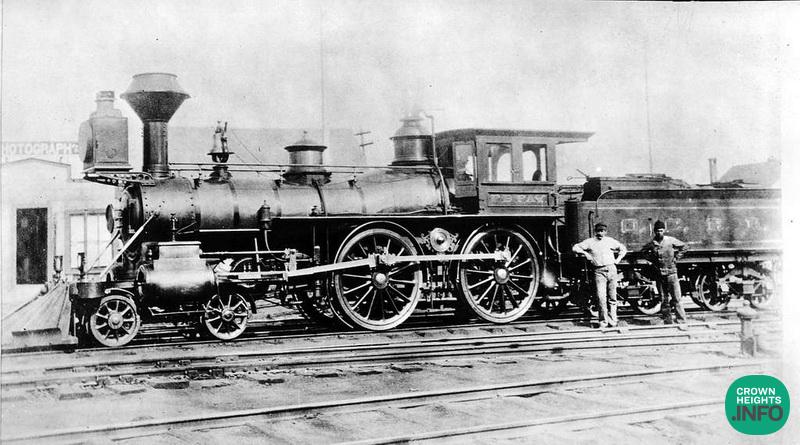

Once in the 1920’s the Frierdiker Rebbe was sitting on a train. Opposite him said an agent of the notorious NKVD. He began berating and belittling the Rebbe and all observant Jews, in a very vulgar way.

During his entire tirade, the Rebbe sat in his seat and did not give any response. When the train arrived at the station that he planned to get off at, the Rebbe stood up to disembark and that person did so as well.

At that point, the Rebbe faced the man and said, “Hayitochen (how is it so), that you spoke such vile language, especially as you were raised in a chassidishe family [it is unbecoming of you]?”

Full of indignation the officer angrily retorted, “How do you know that I come from chassidim?”

The Rebbe responded, “I observed you while you were eating, and I noticed that you had crackers in your hand. However, instead of biting a piece off of it, you first broke a piece off and then ate it, and that is how you continued eating them. That comes from a chassidishe upbringing.” Saying that, the Rebbe left, and the man was utterly stunned.

The man came home that evening and was extremely reflective and thoughtful. In a short time, he made a drastic change in his life and returned to his roots.

The man continued his narrative and said, I know this story because that officer was my father. Not only did he become religious, but he merited to see that all of his children and grandchildren are Shomrei Torah and mitzvos.

When I related this story, someone mentioned to me, without a question, the words of a tzaddik have tremendous power and can change even an avowed atheist. However, often as in this story, the person has to be ready to listen to and internalize the tzaddik’s words, and then it will accomplish its objective.

On Gimmel Tammuz, I heard the following from Rabbi Silberberg.

He noted that when the Frierdiker Rebbe was extremely ill and also when he was arrested, chassidim pledged years to his life.

Reb Elchonon Morosow (known as Reb Chonya) was one of the people who brought this concept to the attention of the other chassidim. In his emotional plea, he stated that he is willing to give away whatever number of years he had, in order that the Rebbe should live.

Now, the purpose of relating incidents and anecdotes of the Rebbeim or the chassidim from the past, is to inspire ourselves and others to emulate these actions. The question is, how, or better said, in what manner, can this story be emulated and applied to us nowadays?

He noted that although this is not being requested from us nowadays in the actual sense, nevertheless it does apply to us in a figurative sense.

Everyone who is connected to the Rebbe does actions that the Rebbe inspires and requests of us. It may be learning with another Jew, encouraging an individual or a group of people to be careful in the fulfillment of a mitzvah, or helping another in a physical sense.

However, while we all do it, there are different ways one can do it.

A person can do it when it is convenient for them. This is commendable, for the main thing is that they are having a positive interaction with another and helping them in one or more ways.

Yet there is a higher way to do this, and that is by giving the Rebbe a part of your life. In other words, I am dedicating or giving a certain amount of time to the Rebbe on a daily or weekly basis.

For that time period, I am not a spouse, a parent etc., which carries its own responsibilities, but at that time I am completely dedicated to fulfill the Rebbe’s wishes and guidance. Those minutes or hours belong to the Rebbe, and that is my focus.

A Taste of Chassidus

Boruch Hagomel L’Chayovim Tovos 5733

When the Frierdiker Rebbe was released from his exile in Kostroma, he said four ma’amorim (chassidic discourses) to commemorate the occasion. One of those ma’amorim was on this verse.

This verse or better said, this blessing is said by an individual who was in a life-threatening situation, and fortunately remained alive and healthy. However, the person is acknowledging that his survival was not a natural occurrence but rather it is a result of Hashem’s kindness and mercy and proclaims so publicly, by reciting this blessing.

However, one may ask, the code of Jewish law states that one who passes by a place where they experienced a miracle says, “Blessed be the one who performed a miracle for me in this place.” So why when that same person says this blessing, they are instructed to say “Blessed be the One that showed kindness to one that was guilty” (and subsequently perhaps deserved a harsh punishment)?!

To answer this, we must clarify which people are obligated to recite the above

mentioned blessing.

Our sages inform us that there are four categories of incidents that mandate this blessing:

1. One who was seriously ill and was healed.

2. One who crossed over the rivers or oceans.

3. One who was imprisoned and faced the possibility of a death sentence.

4. One who traveled through the wilderness.

We know that the Torah came down from heaven (a spiritual aspect) into this physical world. Subsequently, this means that these four categories are referring to a Jew who is in a serious spiritual danger. We will now explain what each category is referring to.

1. A sick person means their health is not up to par. This represents a person whose mind (intellect) and heart (emotions) are dulled, preventing them from truly comprehending a thought of G-dliness and being inspired by it.

2. One who traversed the seas. This is a reference to a Jew who is occupied with earning their livelihood, and as a result of this preoccupation is not focusing properly on serving Hashem.

3. A prisoner is bound by chains; this is referring to a Jew who is bound to the physical attractions that the world offers.

4. One who traveled through the wilderness. The possuk states that a wilderness is a place where man does not dwell. Chassidus explains this to mean that a wilderness is a place of snakes and scorpions, a dangerous place, devoid of man. ‘Man’ is referring to Hashem, meaning that it is lacking spiritual attraction. Simply put, the person who is in the wilderness is too caught up with everything but G-dliness.

Anyone who finds themselves in any of these groups, is obligated to elevate themselves to a higher level, and bring more G-dliness into their life. And indeed, this is a common thought that he discussed in all four ma’amorim after his liberation.

We can now answer the question.

The common translation of the Hebrew word Chayov is “guilty”, as in the case when a judge informs one of litigants that they are chayov – guilty.

However, there is another meaning to this word and that is you are obligated, (which is the extension of a litigant being guilty, subsequently that they are obligated to pay).

So we are saying and praising Hashem for extracting us from that spiritual danger, that in essence we were responsible to do on our own, but in His tremendous kindness, He noticed our distressed situation and gave us the strength that we thought was lacking in us, which allowed us to elevate and extract ourselves from one of those four situations.

This is also the deeper meaning of Boruch, which we previously translated to mean Blessed be the One, however, in a deeper sense it means to bring down the power and ability that is in the spiritual realms to help us in this physical world.

Rabbi Avtzon is a veteran mechanech and the author of numerous books on the Rebbei’im and their chassidim. He can be contacted at avtzonbooks@gmail.com

Mushkie

Can one really “give” her years of life to another person? I know the Midrash of Adam giving 70 years of his life to Dovid, but maybe because Adam was a neshama klali. Really 2 questions: Can a person just give his years to another? And if so, is she permitted to do so, because she is shortening her life and mission on Earth? Are our years something we can give or trade like a piece of clothing??

Mushkie

On that topic, someone pointed out that there is a mishna in Sanhedrin 18 that when a Kohen Gadol suffers the eloss of a relative, we tell him, Anu Kaparasc’ha, we are in your place for the suffering due to you. Thus we see that one can (at least say) that she is taking upon herself the suffering of another person. Does that work and also apply to granting another one’s years?

Mushkie

Further, someone else pointed out that if a person is required to fast for personal reasons, another can fast in her place (Ma’avor Yabok). Some would pay another person to fast for their own attonment. But this all seems odd! Hahsem granted someone a specific amount of years. Can another person restructure the plan by giving that person some of their own years?

Mushkie

How can it work if Hashem decreed suffering on a person for their sins, and another` accepts the suffering upon herself? If Hashem deducted years from a person for their sins, can another person accept that punishment??? Wouldn’t every mother give up years of her own life for the sake of her child??? I am so confused!!!!!!!!!

Rabbi Sholom Avtzon

Your questions are valid and in general you are correct.

However, perhaps I should have noted it, let us take the story of Rebbetzin Devorah Leah. We know for a fact that she indeed passed away a few days later, while her father the Alter Rebbe continued to live for an additional twenty years.

However, as you are aware it didn’t happen just because she offered it. The Alter Rebbe sent a messenger to the tzaddik HaRav Levi Yitzchok of Berditchov, that he should agree and pasken that the exchange can indeed be done.

Simarlily, when the chassidim gave years to the Frierdiker Rebbe it was done with a Beis Din. So it is not just a person says so and it is automatic.

Then comes a second point to consider. As you write, how can a person do this or something similar?

But you are assuming that it is the person who is making the switch. In reality it is that the person is pouring out their heart to Hashem that He should accept this request and plea of theirs.

Then there is a third point. The Rebbe notes in a maamar, that a wealthy person came to the Baal Shem Tov and requested a brocha for a child.

The Baal Shem Tov replied, if you are willing to relinquish your blessing of wealth, you would be blessed with a child and the person responded, yes. He lost all of his possessions but his wife gave birth to a healthy child.

The Rebbe explains, that being that he was granted kindness by Hashem, the tzaddik redirected the kindness to a different aspect.

At the same time we know that tzaddikim often give a brocha for a child, health and many other things, without removing Hashem’s kindness from a different aspect.

Concerning your question of how can one fast or do something else on behalf of someone else, there is two aspects to consider.

A. Being that bnei Yisroel are considered one body, so therefore it is not really someone else.

B. When one does something on behalf of another Jew, this gives Hashem tremendous pleasure and therefore he fulfills that person’s requests for the person who is in need. As the Rebbe Rashab explained to the Frierdiker Rebbe by his mitzvah, that a father has enjoyment seeing that his children are looking out for each other and therefore before we begin to daven we say I am accepting upon myself the mitzvah of loving another Jew as myself.

Furthermore, if you see an item that is hefker, and state I am.picking it up for a certain friend, it belongs to that person and you are not allowed to change your mind and keep it. This is the concept of doing something good on behalf of someone else, and it is considered that they did it.

So yes, we say Tehillim, give tzedokah and even fast on behalf of others.

Concerning your question when this is permitted and when not, that should be asked to a practicing Rov, and being that I am not a practicing Rov, I will not respond to it.

Mushkie

Rabbi, Thank you so much for taking the time to clarify this perplexing and confusing subject. Very few people have the clarity and courage to answer logically and with authority. I am sure many people think about the question but just sweep it under the rug, which doesn’t work for the youth of today. We want answers and are fortunate that you are willing to give the answers we seek. Thank you!!!!

Anonymous

“if you see an item that is hefker, and state I am picking it up for a certain friend, it belongs to that person and you are not allowed to change your mind and keep it” – but Rabbi, I read a Midrash that when Adam reached 930 years, he changed his mind about the 70 years he gave to Dovid. Hashem showed him the “contract” that was signed and witnessed. So we see a person “can” change their mind?

Sholom Avtzon

One can change their mind if the other person didn’t acquire it already.

But when you picked it up for a friend, the friend immediately acquired it. It is theirs, so you can’t take it out of their possession.

Anonymous

Thank you! You are the BEST!

Gedalia

These comments are very precious. To get the youth to engage in the conversation, and to educate and inform them. And us old timers, we also learn and get inspired from them.