History of Crown Heights: The Farband – 305 Kingston Avenue

by Crown Heights Historian Shmully Blesofsky VIA his Instagram account History of Crown Heights.

305 Kingston Avenue is a building with a uniquely designed exterior and an interesting story. Located in the heart of Crown Heights on Kingston Avenue and Union Street, the building is home to a Kollel, several stores, Tzach headquarters, and a children’s library. It is still referred to as “The Farband” by longtime Crown Heights residents. Let us explore its history.

In 1898, when Frederick Rowe, a real estate developer, formed the Eastern Parkway Company, he envisioned Crown Heights as a “Restricted quiet neighborhood.” He even proposed erecting pillars at the Eastern Parkway junctions on Brooklyn and New York Avenues to limit traffic. Rowe also saw Kingston Avenue as a residential thoroughfare with few commercial buildings. In 1909, in character with the neighborhood, developer M.F. Gleason, the builder of 784 and 788 Eastern Parkway, purchased a 40×100 lot on Union Street for $3400 where he erected a three-story residential house with an “Elegant new cornerstone circular front” on the corner of Union and Kingston. A hosiery, a tailor, and a bootblack were rented out along Kingston Avenue starting in 1912.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle Brooklyn, New York Thu, May 27, 1909. Developer record of M.F. Gleason purchased the lot.

Circa 1923. Union Street and Kingston Ave towards Eastern Parkway with a residential house at the corner which would be demolished in 1930 to make way for a building.

Same view circa today.

By 1920, the Kingston Avenue subway station was completed, and the development of the neighborhood was in full swing. In 1930, despite the onset of the Great Depression, two leading developers of the United Improvement Corporation of Brooklyn purchased the first two homes on Union Street. They announced plans to demolish them and build a 40×80 “Business building” for $35,000. Unlike other areas in the city, demolishing an already established structure was extremely rare for the neighborhood but reflected the commercial change that overtook Kingston Avenue. (The commercialization of Kingston Avenue was solidified in 1924 when the Municipal bank moved in on Kingston and Eastern Parkway.)

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle February 27, 1930, announced the new building.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 29, 1930

The developers hired architect Morris B. Adler, who deviated from the traditional brick design and created an Art Deco-style building with a cast stone terracotta facade. It had “Choice Stores” of different sizes along the ground floor on Kingston Avenue, a main hall on the second floor, and a Bowling & Billiards in the basement. The main entrance to the upstairs hall and the bowling alley were on Kingston Avenue, while the emergency exit was on Union Street. The Union Street emergency exit later became the entry stairway to the Kollel.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 12, 1930, advertised the stores for rent at the newly built building.

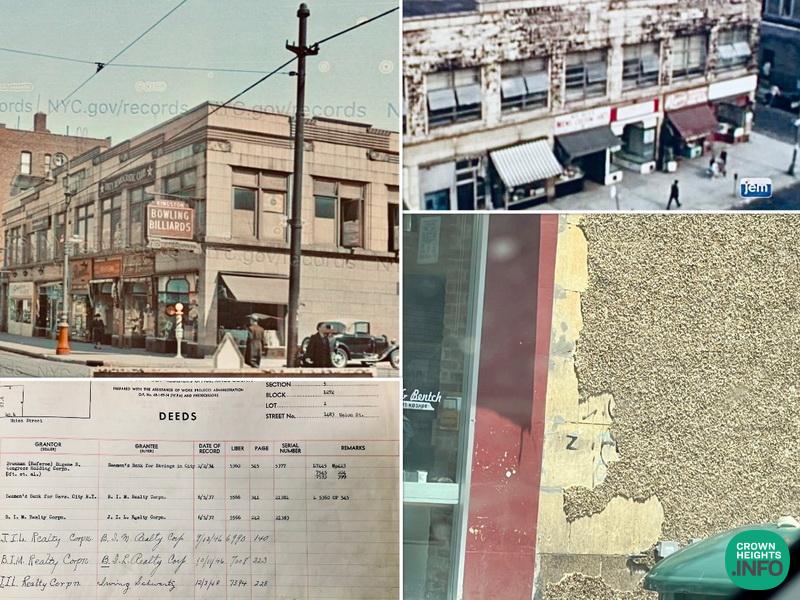

Circa 1940, The Farband Building on Union and Kingston. Note the ‘Kingston Bowling Billiards’ and ‘Unity Democrat Club’ signs.

A duplicate of the building built on Western and Atlantic by the same developer and designer.

The building was an immediate success and became a bustling center of social activism, specialty dress shops, political party headquarters, and a bowling alley. In the 1930s it housed the Wolkoff Tolerance Society, which in addition to “Spreading tolerance” raised funds for Jewish charities and organized an annual ‘matzah drive’. Politicians from all over the city frequented the venue to deliver speeches and engage with the community. Mayor John Patrick O’Brien spoke at their opening.

Times Union Brooklyn, New York Tue, Jan 16, 1934

The great depression did have its effects and in 19334 the building went into foreclosure.

The record of the city deeds. Usually deed records start from 1898 but here they only start from 1934

The Farband Culture Center, the ‘Yiddish Natsionaler Arbeter Farband’ or the Jewish National Workers Alliance, purchased the building in 1952. The Farband was a socialist, Yiddish speaking labor Zionist movement across America and they purchased this building for their Crown Heights local. There was a bigger Farband on Utica Avenue. The Labor Zionist party engaged in various activities, including oneg Shabbat, housing and health insurance for its members. The building was subsequently referred to as the as the “Farband” (association in Yiddish).

In the late 1960s, the neighborhood underwent significant changes and the Rebbe sent a directive, a “Tzetel,” to a community activist, Rabbi Leibel Alevsky of Tzach, saying, “Does Tzach have anything more important to do than helping in the Shchuna?” Subsequently, Rabbi Alevsky worked to ensure that real estate stayed in the hands of the community.

When they got word that the Farband was about to be sold to a club some leading community members including Mendel Shemtov and Rabbi Alevsky worked on purchasing the building. Story has it that at first Rabbi Chadakov asked Mendel Shemtov to approach the Farband and inquire whether they would remain in Crown Heights if offered funds. They responded that the issue was not financial but rather a lack of people. When questioned about why Lubavitch was offering money to essentially anti-religious Jews to stay in Crown Heights, Chadakov explained in Yiddish, “Es iz an ort vos Yiddin kumen tzuzamen, darf men dus shtitzen,” meaning “It is a place where Jews come together, it need to be supported.” Historically, it is clear that such an action taken by Rabbi Chadakov was a directive from the Rebbe, especially if he was offering funds and to such an organization. This aligns with the Rebbe’s commitment to supporting Jewish organizations, even if it involved assisting groups that were explicitly anti-Lubavitch.

Consequently Mendel Shemtov with Rabbi Alevsky and others put considerable pressure on the Farband not to go ahead with the sale to the club and instead sell to Lubavitchers. They weren’t dealing with local Crown Heights residents who may have understood Lubavitch’s conviction, but rather, they were negotiating with the directors who didn’t care much for the neighborhood. They applied significant pressure on the Farband and even reached out to the then-president of Israel, Zalman Shazar, to ensure that the building stayed in Jewish hands. Despite the fact that the Farband had an offer for $100,000, they succeeded in bringing the price down to $60,000. Tzach was able to purchase the building by assuming two mortgages which was paid for by the stores below and paid a small amount in cash.

The Farband circa 1960s. Notice the castone façade fading.

Circa today some of the original castone showing.

In 1970, as the building fell into decline, Horav Dovid Raskin, a founding member of Tzeirei Agudas Chabad (Tzach) for decades, had the task of making the building usable for Tzach activities, asked Reb Aharon Blesofsky to assist in the renovations. Being that the cast stone was wearing out, the facade was given a facelift by covering the outside with aggregate stone, which is essentially pebbles spread on a paste cement. Colored pebblestones and specific patterns were chosen to accentuate the building and the stores along the Avenue, and that facade remains to this day.

In 1972, the Yeshiva Bochrim’s Seder was held at the newly purchased Faband, and the Rebbe came to visit as he would every year. After a short sicha to the bochurim and visiting the kitchen to wish a special Good Yom Tov to the Yeshivah cook Mussia, the Rebbe headed down the stairs with Yankul Katz at his side and the bochrim in tow. The Rebbe appreciated all the work Yankul Katz did for the Frierdicker Rebbe and that is why they walked together. When they got to the bottom of the long staircase, perhaps noting its length and Katz’s advanced years, the Rebbe said with a smile, “Es is tzvei un tzvantzivk trep!.” “There are 22 steps!”.

Following Tzach’s purchase, the changes were palpable. Where the ‘Unity Democrat Club’ once held their meetings in the upstairs main hall, they now held the gatherings known as Pegishas. Where members of the Farband once earnestly spouted their Socialist ideals in Yiddish, was now available to host an engagement party L’chaim for a mere $60. The double-wide storefront club center where Harry Wolkoff’s fantasies of spreading tolerance were spoken has now transformed into Crown Heights’s beloved Kievman’s Shoe Store.

The once brand new fancy “Choice stores” on Kingston were able to accommodate the businesses when the viber-shul was built across the Avenue. While a big story in 1936 was about a $16 hold-up at the Kingston Bowling & Billiards function in the basement, that area was now turned into Tzach’s main offices and the Levi Yitzchok Library for children. Finally, where the barber shaved the locals’ beards for over 30 years, now turned into the home of the World Lubavitch Communication Center (WLCC). Coincidentally, where there was an unnoticed large closet at the top of the staircase leading into the main hall on the 2nd floor is where Mr. Johnny Hackner now gave haircuts to yeshiva bochurim.

Today, 305 Kingston Avenue boasts the Crown Heights Kollel, offices of Tzach, Sarai wig shop, the Mercaz Stam bookstore, Union Car Service, See View Optical, and the busy Ess-and-Bentch eatery. Tzach’s main offices and the newly renovated Levi Yitzchok Library are still down the stairs from the entrance on Kingston Avenue, and we know for certain that the building will be part of the neighborhood’s ever-developing story as the community grows.

Shmully Blesofsky All Right Reserved.

(For reprint permission sblesof@gmail.com)

Update:

Sarai wig shop has now been replaced by Hidden Treasures jewelry store

The Rebbe

I had heard that the Rebbe himself even got involved in making sure this property, right across the street from 770, wasn’t sold to a club.