A U.S. Assistant Treasury Secretary’s Passion for the Chassidic Masters

by Yaakov Ort – chabad.org

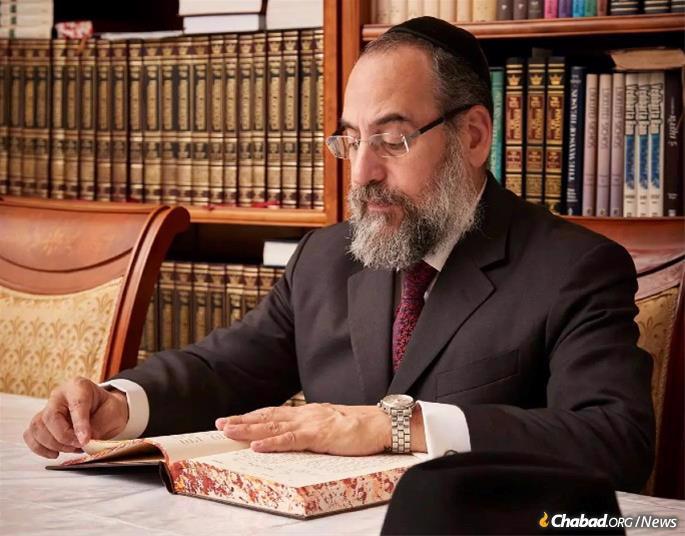

Throughout his life, Moyshe (Mitchell) Silk has been immersed in three extraordinarily diverse civilizations and the languages that are foundational to them.

Raised in a Jewish home in Chicago, his first language was English. A mastery of the language served him well at leading U.S. universities and law schools, where he became an acclaimed lawyer and legal scholar, and later when he served in the Trump administration as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for international markets. In his voluntary life as a champion of religious rights, Silk employs English prose and legal argument in leading large teams of pro-bono attorneys for Agudath Israel of America.

Silk learned to speak Cantonese while working in a Chinese restaurant during high school. He later mastered Mandarin Chinese in college and developed a deep understanding of Chinese history, philosophy and ethos through academic study. As one of America’s leading experts on Chinese law and finance, he writes and speaks Chinese in his interactions with Chinese lawyers, economists and officials, and in his many visits to China.

Applying his continuing study of Hebrew and Yiddish, Silk became an acclaimed editor of the works of early Chassidic masters, including his recent groundbreaking translation and commentary on Kedushas Levi (sometimes rendered “Kedushat Levi”), by the seminal Chassidic master, Rabbi Levi Yitzchack of Berditchev. He has plans to supervise the English-language translations of similar such works which are still available only in Hebrew.

In a wide-ranging interview with Chabad.org, Silk, a resident of the Boro Park neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., discussed the impact of Jewish, American and Chinese cultures and values on his life and work; his lifelong fascination with languages in general and Hebrew and Yiddish in particular; and his deep desire to spread the teachings of early Chassidic masters to the English-speaking public through accessible translations of their works.

Q: How do you approach learning a new language? How did you become fluent in Chinese, for example?

Immersion and a ton of hard work were two basic keys to my mastery of two dialects of Chinese. The manner in which I gained fluency in both dialects is interesting, full of hashgacha pratis (“Divine Providence”) and illustrates the importance of immersion when learning a language.

My family circumstances required me to go out and work at a young age. I was born in Chicago, where all of my grandparents settled from Galicia in the early 1900s. My family moved to South Florida just before my bar mitzvah. Shortly afterward, I took a job in a restaurant to help supplement my mother’s income. A Chinese family emigrated from Hong Kong during my first year in high school and moved into a house just across the street from us. Three of the sons of that family were in my immediate age group, and I spent a lot of time with them helping them get accustomed to the United States. One of their relatives owned a Chinese restaurant just two blocks from our house, and I was offered a job in the kitchen.

It was tough work. I manned the dishwasher, and before the dinner rush started, I would help out with prep in the kitchen—mainly peeling and chopping onions and cabbage (that came in 100-lb. sacks). The work was physically challenging and there was no air conditioning in the kitchen! Shvitz we did! I became quite proficient with a Chinese cleaver, and could get dishes scraped, rinsed, through the machine, dried and stacked in no time. I gradually worked my way up to a busboy and, then, finally, waiter.

No one in the kitchen spoke English, and it became abundantly apparent to me that I needed to speak the lingo to get my orders in and my food out of the kitchen efficiently. Thus began my six-year journey to master “Chinese.” My learning experience involved a lot of critical listening, and showering my friends with questions on how do you say “this” and how do you say “that.” The listening part was critical because Chinese is a mono-syllabic tonal language—every character is pronounced in one syllable (some words comprise compounds of two or even three characters) in one of many tones. If you got the tone wrong, you would be saying, unintended, something completely different than what you meant. Take the word chou in Mandarin. Depending on the tone, the word can mean smoke (as in smoke a cigarette), worry, ugly or smelly! Imagine telling someone they looked worried, getting the tone wrong and telling them that they smell! Oy!

After two or so years, I was pretty good. I had a solid basic vocabulary and had mastered the tones. My fluency and ability to express myself was solid enough. I was certainly able to get my food out of the kitchen with ease enough to keep my customers happy. But then, I got the shock of my life when about three years in I learned, one fine day, much to my consternation, that there was more than one dialect of Chinese. In fact, there were eight major ones! Oy vey! And … the dialect that I had learned (Cantonese) was spoken by over 90% of the Chinese in America, but only 5% of the Chinese in China! Oy vey iz mir! The official language of China is Mandarin Chinese, and Cantonese is only spoken in the Southeast province of Guangdong. The vast number of Chinese immigrants to the U.S. until around the 1980s were from the Guangdong Province, explaining why Cantonese was so prevalent in the U.S.

I needed a plan, then, to master Mandarin. A friend of my late father made a great suggestion. Why not go to the Summer Chinese program at Middlebury College? During the summer, Middlebury turns into an intensive foreign language training ground. In my day, they offered 11 different languages, including Hebrew. It was a nine-week intensive program that offered a full year of college credit. There was one catch. You had to sign an undertaking as a condition of attendance to speak only the language you were studying during the course.

Well, it worked! I had a truly wonderful summer in idyllic Middlebury, Vermont, studying Mandarin Chinese with a passion. From there, I spent the next academic year studying Mandarin and related China subjects (in Chinese) at the National Taiwan Normal University. It was full immersion because very few people spoke English in Taiwan at that time.

Those couple of years really defined my professional career since China and Chinese factored so heavily into my law practice. And my fluency in Chinese and experience in China transactional work were key reasons why the Trump administration tapped me for a senior position at Treasury.

Who would have thought that working in a Chinese restaurant would have led to a presidentially nominated, Senate-confirmed senior leadership position in the federal government? With immersion, a little hard work, subject matter interest and the usual dose of hashgacha pratis, you can achieve all you desire—the sky’s the limit!

Q: What is it like to master such different means of communication? English reads from left to right, Hebrew from right to left, and Chinese reads vertically from top to bottom. What’s to be learned by the fact that these different civilizations communicate in such different ways? Do you have any advice for those engaged in cross-cultural communication?

A: Every language has its own cadence, intonations and idiomatic expressions, all of which have linguistic significance, are informed by relevant sociology, history and culture, and are highly nuanced. Mastery means a command of not just pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar and syntax, but, perhaps more importantly, all of the highly nuanced soft sides of the language. The “soft sides” include those very intonations and manners of expression and the sociological, historical and cultural underpinnings of the language.

“Cracking the code” of a new language is so much more than breaking one’s teeth on differentiated pronunciation, seeming endless hours of rote memorization of words and making sense of rules of foreign grammar. Every language has its unique sociological, historical and cultural foundation. That is the interesting study of linguistics. It is impossible to understand, appreciate and certainly master a language in isolation from its rich sociological, historical and cultural underpinnings.

Conversely, the deeper the student’s understanding and appreciation of a new language’s foundation, the quicker and more efficient his grasp of the language will come. If a person wishes to speak the loshen (“language”) of the Gemara, that student must understand life in the time of the Gemara. If one desires to engage an older Chinese person in the hinterlands of China in his mother tongue, the speaker must come with not just monosyllabic sounds rendered in the correct tone, but also have a sufficient appreciation of 5,000 years of Chinese history, local circumstances in that piece of the Chinese hinterland and some general knowledge of Chinese culture. If you wish to convey your thoughts to someone who speaks a language other than yours, you will be infinitely more successful in getting your point across by knowing that person, and his/her native country’s culture and history.

Q: Your translation and commentary of Kedushas Levi includes both the original Hebrew, and in English, translation and commentary. If the goal is to communicate the Chassidic concepts to an English-speaking audience, why was it important to include the Hebrew original as well?

A: Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev, who is sometimes known by the title of his opus as the Kedushas Levi, recorded his chochmah or “core essence” of his monumental work, the Kedushas Levi, in the “Holy Tongue”—Lashon Hakodesh, as is the case with all of our great works, whether nistar [the esoteric parts of Torah] or nigleh [the exoteric]. Our version of the Kedushas Levi is a learning tool that assists in unlocking the meaning of the work to those who do not have a command of Lashon Hakodesh or otherwise needed a learning aid to greater or lesser extents. Our version is not meant by any means to replace the original sacred and authentic version of the work. Rather, we hope that our work will serve as an important learning aid or tool in making the work more accessible to the English-speaking world. There are many phrases and terms that we simply are not able to render exactly or perfectly in English. In addition, it is important to have easy reference to the original Hebrew for precise terminology—the quotes from classic sources like Tanach or Talmud—while reviewing the English.

Chassidus and all of Torah is meant to be learned in the original Holy Tongue. And, alas, there are many—from learned scholars to the uninitiated—who need and want a learning aid. We set out to provide that learning aid by presenting the original text of the Kedushas Levi along with a readable, accessible and flowing English translation that is true to the original. We hope that we have provided that important bridge for English speakers to cultivate a closer personal connection with the personage of the Kedushas Levi and the written word Kedushas Levi.

Q: What was the genesis of the Kedushas Levi project from conception to publication?

A: The thought of producing a readable and flowing English translation of the Kedushas Levi and other Chassidic Classics came to me while riding in the back of a little red Lada through Ukraine visiting Kivrei Tzaddikim (“gravesites of the righteous”) in 1996. It has been a journey of passion—at times, a derech arucha uketzra (“a long, short route”), at times a derech ketzara va’arucha (“a short, long route”)—but at all times a very long journey.

Our trip involved visiting a number of tzaddikim throughout Ukraine over a period of just three days. We arrived in Berditchev in the afternoon of our first day. The inside of the Kedushas Levi’s Ohel was barren—just a few volumes of Tehillim, the tzion (“gravestone”) and a shelf above it with a ner tamid (“eternal flame”) made of a glass jar filled with oil and a makeshift wick. But the flame was not burning. It had not occurred to me at the time that the flame had no chance because there was no wick holder, and, tried as I did every which way, I could not get the wick to stay lit.

I couldn’t get the incident out of my head for the rest of the trip, and I decided to take action when I got home from the trip. If I couldn’t keep the physical flame lit at the Kedushas Levi’s tzion, I would bring the light of the Kedushas Levi to the world by making his Kedushas Levi available to the English-speaking world by preparing and presenting an English translation of this great work, as well as other Chassidic classics.

My family has been aligned with Nadvorna Chassidus for over five generations, and I began with a translation of the Ma’amar Mordechai, attributed to the Rebbe, R’ Mordechai of Nadvorna. My team completed a translation of the Ma’amar Mordechai in a little over a year, but after considerable deliberation, I decided that it would be best to publish the Kedushas Levi as the first volume in the series, given its status among the Chassidic Classics.

I did not fathom what all might be involved to get this project off the ground. I just went in head-first, enlisted a few friends who are gifted translators and skilled copy and style editors to form a team. And off we went. It was ultimately a 30-year journey, with personal and professional obligations many times getting in the way and seeming insurmountable translation, editing and production challenges causing significant delays.

The work required a team the size of a small army. I built a team of senior and associate translators, style editors, copy editors and citation checkers. In addition, once we got into the final stages of production, we added a legion of technical experts, covering translation and refinement, design and layout and the like. In all, not less than 30 technical experts supported this effort. Resource management and availability of experts when you need them are highly challenging.

The challenges were many—technical translation issues of accuracy and readability of translation and hitting the right tone and settling on a layout and design that best suited the translation. Toward the very end of draft production, we hit a major snag in that the layout approach we settled on initially did not work well with the translation. As a result, we had to go back to the drawing board, unwind layout work that we had completed for the whole volume and recreate the volume using a completely different layout. This was easily a six month setback. It was hard work and highly tedious, and we finally got there.

Our translation also incorporates some unique features. The volume opens with a lengthy introduction setting the stage on the life of Rabbi Levi Yitzchok and providing a brief overview of the sefer, and a concise overview of the general Chassidic concepts covered in the work. In terms of study aids, the set includes a 40-page subject matter and source index, as well as titles and a few framing sentences for every entry. This latter feature provides simple and clear signaling to the reader on the content of every entry.

It was a long and arduous 30-year journey that I liken to a marathon. I was OK for the first 26 miles; it was that last .2 miles that really got me!

Q: What are some key teachings in Kedushas Levi that would be of greatest interest to a thoughtful contemporary Jewish man or woman?

A: Born in 1740 in Eastern Europe to a prominent rabbinical family, Rabbi Levi Yitzchok distinguished himself at an early age both in the breadth of his scholarship and his unswerving dedication to ordinary people. He was a leader for and of the people. As such, he delivered simple yet insightful insights into human life, behavior, and psychology, and was as concerned with life in the real world as he was in providing profound meditations on Scripture. And because the real world is relentless in challenging us, his great work, the Kedushas Levi, has a lot to say about what to do when our challenges appear overwhelming. His considered and heart-felt words have, for centuries, helped anyone who cared to read his teachings navigate hardships and doubt and inspire them to achieve greater spiritual fulfillment.

The sefer Kedushas Levi is a very accurate and unique reflection of the man, the Kedushas Levi. The Kedushas Levi was unique in so many ways, two most fundamental being the depth and breadth of his scholarship and his love for each and every Jew. The Kedushas Levi was a master of both nigleh (the revealed aspects of the Torah) and nistar (the concealed aspects of the Torah, including what we refer to as mysticism). Reflective and representative of that are the entries of the work that provide profound and deep insights on challenging issues presented by primary sources, as well as profound thoughts on esoteric issues like the creation and on-going function of the world. Beyond that, so much of the content of the sefer is focused on how each and every one of us can be a better person, how we can be a better servant of Hashem, how we can be a better friend, sibling, son/daughter, spouse, business partner or communal member.

His plain-spoken, heartfelt and immensely uplifting messages are timeless truths that help clear the mind, steady the nerves, strengthen faith and Divine service, and ready the heart for whatever challenge may lie ahead. Here are but a few.

The Kedushas Levi also serves as a powerful moral compass. He provides the basic formula for ensuring Hashem’s favor

“The Baal Shem Tov would often [encourage] people [to strive to be better through simple service] by referring to the verse [in Tehillim 121:5] “G‑d is your shadow.” Just as a shadow mirrors the movements of a person, so, too, God, as it were, mirrors a person’s conduct. Consequently, a person must strive to continuously perform mitzvahs, give tzedakah, and be merciful to the poor, so that G‑d bestow favors upon His nation.”

On a related point, the Kedushas Levi reminds us, particularly when preparing for Rosh Hashanah, just how important the concept of reflective justice is.

“Daily, the Almighty judges us with great compassion and kindness. But we have to arouse this compassion by conducting ourselves with kindness and by looking at the positive points of our fellow Jews, judging them favorably.” And he also reminds us that Divine justice is a two way street. “[O]n Rosh Hashanah, when the Jewish people are judged by G‑d, the judgment also applies to G‑d, as it were, because G‑d receives pleasure by giving to the Jewish people. When the Jewish people are worthy and are able to receive His goodness, G‑d rejoices. … G‑d will not focus on your deeds and your merits, but will bestow His beneficence upon you on account of His innate goodwill. … When He confers goodness and blessings on you, He will overlook you and your deeds. … G‑d will not focus on your deeds and your merits, but will bestow His beneficence upon you on account of His innate goodwill. … For G‑d will once again rejoice over you for good, as He rejoiced over your Avos—in order that He derive joy and happiness by us receiving goodness from Him. Amen.”

Again and again, I found the Kedushas Levi to be speaking directly to me—instructing me to see my problems and those of the world from a different perspective and walk away with renewed charges of energy, optimism and faith. Here is a good example on suffering:

For this reason, when any Jew suffers, G‑d forbid, the resultant kindness that is the intended purpose of the suffering has already been prepared. It is only through the sickness that the person becomes a vessel to receive bounty. Just like a person who wants to enlarge a small vessel has to break it first, when G‑d wants to grant a person more copious goodness, He first dispatches some challenge or sickness in order to have the effect on the person of making him greater. Sending a disease or challenge breaks the smaller vessel and enlarges it, that is, it forces the person to become better. So a person afflicted with an illness is analogous to a pot because he becomes a larger vessel through the illness.

Finally, he so simply and elegantly shed light for the questioning or unaware on the purpose of the evil inclination.

A king is truly honored only when his subjects honor him freely. Although they could refrain from honoring the king, they elect to do so. This is genuine reverence for the king. If tribute to the king would be forced, and the subject lacked free choice, this would not be true honor. This is the purpose of the creation of the evil inclination, so that greater honor is accorded to G‑d since it is given freely. Although a person has free choice and an evil inclination, which attempts to persuade him not to serve G‑d, he conquers the evil inclination and thereby sincerely honors, extols, and serves G‑d. This truly glorifies Him. If a person did not have an evil inclination and had only a single option, then his Divine service would not glorify G‑d as much. Thus, “All that G‑d created, He created just for His glory,” meaning that G‑d removed the brightness from one thing in creation, leaving an empty and dark pit, and this refers to the evil inclination. He did this strictly for His honor, so that His honor would be augmented by man’s free choice.

Q: You hope to follow Kedushas Levi with similar endeavors for the works of Chassidic giants whose books have been studied for centuries in Chassidic communities but have not been available in English. What are some of the first works you hope to continue the project with, and why have you chosen them, in particular?

A: As mentioned, in the 1990s, I started working on a project to translate the Nadvorna Chassidic classic Ma’amar Mordechai. My dream was (and is!) to usher that volume in with other Chassidic classics and eventually produce a whole series of like titles. The Kedushas Levi was the volume that I chose to be the inaugural volume of this series. My motivation when I started this project was to make the whole of the Kedushas Levi accessible to a greater audience by rendering in a readable English the thoughts of the great Levi Yitzchok of Berditchev that were originally recorded in classical Hebrew.

My dream from the beginning was to bring to the world a series of the Chassidic Classics presented in readable and flowing English. This is because the rich literature of the Chassidic movement, extant for over three centuries, has grown considerably in quantitative and qualitative contribution to Judaica literature in areas of basic textual commentary, festival and other worship, spirituality, personal growth, ethics and so many other areas central to Jewish life. With few exceptions, however, classic Chassidic texts are heavily underrepresented in the extraordinary literature of classic texts that are now translated into accurate, clear and readable English.

I have over 70 titles on my “wish list,” ranging from works of the Baal Shem Tov (Sefer Baal Shem Tov) to his direct disciples and all the way down to fourth- and fifth-generation Rebbes. After publishing the Kedushas Levi, I have had a few requests for specific titles. My decision on which titles to choose next will be guided by practical considerations. In the next round of work, I will consider (1) the proximity of the author to the Baal Shem Tov, since I would like to focus on earlier generations in the first phase; (2) the book’s accessibility (limited amount of esoteric content); and (3) its length.

I started with the Kedushas Levi because it is befitting “first appearance” prominence—Rabbi Levi Yitzchak learned with the first generation of students of the Baal Shem Tov, and the book is widely recognized as a classic and learned by virtually all Chassidim. It is a long sefer and not without its complex/esoteric content, which increased the degree of difficulty and time of completion. Future works that are briefer than the Kedushas Levi and with more easily accessible content will allow us to complete work in a shorter time period and get to market quicker.

I am hoping and praying for continued divine assistance in this work. My ability to continue will require a dedicated translation and editing team and funding.

Q: You are the first Chassidic Jew to have been confirmed by the United States Senate to a senior position in the federal government. What are some of the most important ways that the values and practice of Torah Judaism and the wisdom of the Chassidic masters, have influenced your life from your first job as a teenager to becoming a leading attorney and a senior representative in negotiations between two great superpowers?

A: Chassidic thought is very much focused on the concept of “energy”—how we can energize the material, and specifically, how we can spiritualize the mundane. Put simply, I have focused as much as utterly possibly on how I can create positive spiritual energy and a Kiddush Hashem (“sanctification of G‑d’s name”) through my work.

I knew in my 30-year career as a lawyer and while serving in government that my every thought, word and action would have a potential impact, and it was up to me whether the impact was positive or negative. And, as an extension of that thought, given my distinct Jewish look—black hat, black suit, white shirt and beard—I also knew that my every thought, word and action had a potential of making a Kiddush Hashem (“sanctification of G‑d’s name”) or a Chillul Hashem (“desecration of G‑d’s name”).

The Kedushas Levi includes a related thought. He provides simple and straightforward views on how we should view our priorities in life.

There are two approaches to lifestyle. One is that of the unenlightened individual, in which it seems to him that working is the main priority. The second approach is that of the enlightened individual, the approach of a person who has a pure heart and who knows the truth, that the purpose of the creation of all the worlds is to study the Torah, to engage in prayer, and to perform mitzvahs and good deeds. He realizes that business and work are only a means to the end, the end being the worship of G‑d. Work, therefore, is secondary to the primary priority, which is the study of the Torah and the performance of good deeds, for they are the ultimate purpose of Creation.

If we can perform our work in so it enables us to learn Torah, serve G‑d and to do acts of kindness—for example, for me to have the kavanah (mindfulness) during work that my work produces a salary that enables me to raise a family of G‑d fearing children, support my community and maybe even get in the translation of a great work of Jewish thought—so that the worldly work is a means to a spiritual end—we then bring added sanctity to the workplace and our work. That’s a double win in my book!