Obituary: Philip Wexler, 79, Scholar Chronicled the Rebbe’s Social Vision

by Bruria Efune – chabad.org

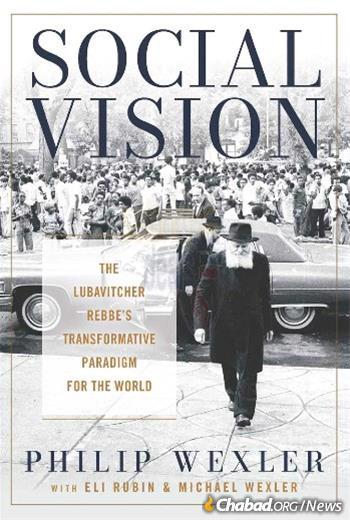

Philip Wexler, a renowned professor and sociologist who devoted his long career to studying the role of education and spiritual practices in the construction of identity, and whose final work— Social Vision: The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s Transformative Paradigm for the World—detailed and reassessed the social dimensions of the Rebbe’s vision and legacy, passed away on March 25 (Nissan 3). He was 79 years old.

Raised in Brooklyn, N.Y., by Max (Mordechai) Wexler and Mindy Wexler, the young scholar graduated from New York University and earned his Ph.D. from Princeton University. He was then awarded fellowships by the Woodrow Wilson Institute and the National Institute of Mental Health. He was also a Lecturer in Sociology at Queens College, City University of New York, and a visiting professor at Griffith University, Australia.

A professor on the faculty of the University of Rochester since 1979, Wexler became dean of the School of Education in 1989. Five years later, he was appointed to the newly created Michael Warner Scandling Chair, with the school also being renamed the Margaret Warner Graduate School of Education and Human Development. While serving as dean at the University of Rochester, he was also named Distinguished Best Practice Professor at the University of Newcastle in Australia. He later served as the founder and Executive Director of the Institute of Jewish Spirituality and Society.

Throughout his academic career, Wexler was especially concerned about the need to counteract the modern sense of alienation that increasingly erodes self, relationships and community. His concerns about society were as practical as they were theoretical. On being appointed dean at the University of Rochester, before the advent of the Internet, he expressed his concern that people were not being educated in a way that would equip them to deal with the “electronic information network” or “to understand and control the symbolic [virtual] environments in their lives.”

In other words, he understood the implications of the Internet age and the dangers of social media before social media even existed.

In a 1992 New York Times feature on education, he said that the most important thing missing from schools “is a sense of community.” Teachers need to “pay attention to kids as whole people” and take care of “their needs as members of society” rather than only “looking at them as thinking machines.”

Rabbi Nechemia Vogel, director of Chabad-Lubavitch in Rochester, met Wexler nearly 30 years ago when Wexler attended the rabbi’s class in Tanya, the foundational work of Chabad philosophy.

“We did quite a bit of learning together and became good friends,” Vogel told Chabad.org. “He was a brilliant man, very accomplished and prominent in his field, yet he was always kind and gentle and had a humility about himself that was truly remarkable.

“We had many lengthy discussion about Chassidic philosophy and about the Rebbe [Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory] in particular,” Vogel recalled. “Despite the fact that he already knew so much, whenever he encountered something he hadn’t learned yet, he was eager to delve into it, to immerse. Once when we were studying a particularly deep teaching of the Rebbe, he stopped and looked up at the picture of the Rebbe on my wall, and said: ‘You know, I wish I could have met him.’ Through his deep analytical thinking into the Rebbe’s teachings, he developed his own connection, which later grew into Social Vision, which so excellently expresses much of the Rebbe’s message to the world.”

Mid-Career Pivot to Jewish Studies

In the early 2000s, Wexler was at the height of a successful career. Intellectually, however, he was restless. The modern academy was now so specialized that sociology was at risk of simply repeating old ideas without finding new solutions.

Wexler felt compelled to make a mid-career pivot and start out on a new path. It had much to do with a growing coherence about his own identity as a Jew and a descendant of rabbis, and with his discovery of the socio-mystical teachings of Chassidism. But it was also informed by his deep reading of the founding fathers of sociology, Max Weber and Émile Durkheim, who grounded their study of society in the study of religion.

In 2001, Wexler went on leave from the University of Rochester and took up a fellowship at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. Soon afterward, he was appointed professor of sociology of education and then Unterberg Chair in Jewish Social and Educational History, at Hebrew University. He also directed the School of Education at Hebrew University. Between 2008-09, he convened a year-long international working group at the Institute of Advanced Studies in Jerusalem. In subsequent years, he served as a visiting professor at Brandeis University in the United States and at the Bergische University of Wuppertal in Germany.

Beginning in 2012, Wexler began organizing a series of international conferences that brought together scholars from different disciplines in the humanities and the social sciences for workshops and conversations that were designed to advance both scholarship and social transformation. As someone whose own career bridged very different spheres of study, he had a unique ability to bring diverse groups of people together, encouraging them to step out of their intellectual comfort zones and engage in generative discussions that moved from theoretical analysis to practical application. These meetings led to the establishment of the Institute of Jewish Spirituality and Society, with its mission to advance scholarship and social transformation.

His research and teaching in the U.S., Israel and Europe developed into a number of books and lectures, especially in Mystical Sociology: Toward Cosmic Social Theory (Peter Lang, 2013) and in his final work, Social Vision: The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s Transformative Paradigm for the World (Herder and Herder, 2019).

Immersion in the Chassidic World

“Mainstream culture, mainstream politics and mainstream intellectual discourse all seem increasingly and inexorably commercialized, reduced either to tokenism, or to frivolity, if not to endless futility and to the weighty grind of work, work, work.

“Is there a way to repair society?” he asks.

Wexler’s desire to find a sociological route by which to escape this paradigm led him to leave his career in traditional sociology behind and to extend the horizons of his research to include the Jewish mystical tradition in a search for a new sociological beginning. He explained that he was most motivated to find a path by which humanity could escape the iron cage of the capitalist order, and on the way, analyze why religion had not only survived the scientific revolution but was even thriving.

Through his acquaintance with the Chabad Chassidic world, Wexler became inspired by its practical philosophy, in his words: “Hasidism does not bifurcate the paranormal from ordinary life in the world, but rather integrates the paranormal within the normal.”

Wexler studied the Rebbe’s talks and writings. He was impressed by a leader who sought to address some of the most pressing social and political problems of our own age from an explicitly Chassidic and mystical perspective, and did not simply assent to agendas emanating from sources external to his own tradition.

Judaism and Social Connectedness

Through Chabad Chassidism, Wexler found a new way in which education can be at once social and critical, but also religious, spiritual and mystical, producing enhanced measures of agency and social connectedness.

Wexler became acquainted with Rabbi Eli Rubin, a writer and editor at Chabad.org, at the University of Pennsylvania, where Rubin was involved in organizing a conference focusing on the theory and practice of education in Chabad. Rubin, who would become Wexler’s co-author of Social Vision, recalls how the relationship developed over several years. Although Wexler was many decades his senior, he was treated like an equal almost from the outset.

“With time,” remarks Rubin, “and through many conversations and study sessions together, it began to feel like we were thinking together. He was fashioning a new set of conceptual tools through which to study and understand Chassidism as an intellectual and social movement, and specifically to understand how the Rebbe used ideas, words, to galvanize activism and thereby engineer a transformative renaissance of Jewish life.”

Rubin remembers when he and Wexler had been deep in the midst of researching Social Vision. They had been planning the book and doing a lot of reading and talking, but still didn’t have a clear roadmap. “One afternoon we watched a video recording of a farbrengen of the Rebbe. It was several hours of talks on different topics, interspersed with singing. It was almost an immersive experience, as if we were embedded in the crowd, and able to get a real sense of the social dynamic that the Rebbe was orchestrating. For Philip, it seemed as if the whole book came together though that ‘participation’ in the farbrengen. Afterward, we went outside and sat at a table overlooking Keuka Lake in Upstate New York. There and then, he dictated the entire outline of the book to me, chapter by chapter, while I scribbled away furiously on a yellow pad.”

Social Vision would go on to earn extraordinary praise from a wide variety of academic sources. William B. Parsons, Professor of Religion and Culture at Rice University, called the book “the needed prescription for our times.” Jonathan Garb, Gershom Scholem Professor of Kabbalah at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, said the work “may well become the foundation of fresh sociological thought,” and was “a model for socially meaningful scholarly writing.” Rachel Werczberger, Professor of Sociology at Ariel University, noted that Wexler’s “artful and engaging study will be of great interest to scholars of religion, spirituality and society and to educated readers alike.”

Jonathan D. Sarna, Professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis University, said Wexler “illuminates the Rebbe’s distinctive views on American society, the role of the individual and the community, the purpose of education, and much more.” He called Social Vision “a bracing introduction to the central ideas that shaped Chabad-Lubavitch in America.” Ellen Koskoff, Emerita Professor of Ethnomusicology, the Eastman School of Music at the at the University of Rochester, said Social Vision was “an extraordinary portrait of a visionary leader whose message continues to be both relevant and imperative for us, today.”

Over the course of several decades, Wexler wrote and edited more than 15 books and dozens of scholarly articles. He also served as a mentor to hundreds of students and colleagues, many of whom went on to forge distinguished scholarly careers of their own.

Above all, he held his family near and dear to his heart.

In addition to his wife, Ilene, he is survived by their four children, Michael Wexler, Ari Wexler, Helen and Ava, as well as by four grandchildren. He was predeceased by his sister, Helen Wexler.