Here’s My Story: The Ultimate Rush Job

Rabbi Leibel Altein

Click here for a PDF version of this edition of Here’s My Story, or visit the My Encounter Blog.

When the Previous Lubavitcher Rebbe escaped from Warsaw in 1940, he was forced to leave his precious collection of books behind. Part of the library was rescued the following year, but the rest of it was lost for the next few decades. In 1977, a large portion of the books was discovered in a museum in Warsaw, and they were redeemed and brought to America.

A few months later, the Rebbe declared his intention to create an institution to publish and distribute the manuscripts of chasidic texts contained in the collection, and called for volunteers to get involved.

One of these manuscripts was a Tanya, the basis work of Chabad philosophy, authored by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, also known as the Alter Rebbe. Only this manuscript of the Tanya was different from the printed version we have; it was the first draft of the Tanya.

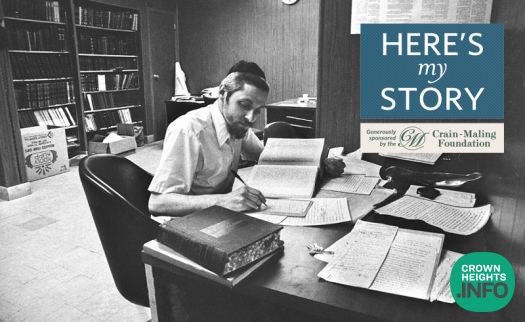

At that time, I was working for Vaad L’Hafotzas Sichos, transcribing, editing and publishing the Rebbe’s talks. Over the next couple years, a few items from the collection began to see the light of day, and then, in the second half of 1981, the Rebbe wrote to the Vaad that we should undertake to print this original draft of the Tanya.

Now, besides this manuscript from Warsaw, there were several other old and variant manuscripts of the Tanya. Our work, then, would entail comparing all of these various written versions with the printed Tanya.

This is technical, difficult work and it wasn’t our specialty. But, we asked the Rebbe exactly what he had in mind and, after he told us how to edit and print the book, we got started.

The task was overwhelming, and it was in addition to our existing job of publishing a booklet of the Rebbe’s talks each week.

Working on those booklets, which bore the Rebbe’s name, was a serious responsibility, and put us under tremendous pressure; to make sure we were capturing his intended message, we had to study his teachings in depth. In order to begin to get an inkling of what the Rebbe was saying, we had to first familiarize ourselves with every aspect of the Torah subject under discussion, and then try to grasp his innovation on the topic. And remember, back then there were no electronic databases where we could search for things – we simply had to learn a lot.

At times, the Rebbe could be quite critical if we had not understood or properly written up a particular point. Sometimes we would receive a sharply-worded rebuke, but when that did happen, there was no time to dwell on it because we had to keep going to get the next issue ready.

So, preparing this publication was already a 24/7 job, and now we had the Tanya on top of it. The Rebbe also said that he wanted it ready for the 19th of Kislev, the anniversary of the Alter Rebbe’s 1798 release from Czarist prison, so we literally moved into our office. We simply left home and spent all day working like madmen.

Because much of the text was identical in the different versions of the Tanya, but some parts were different, comparing the manuscripts, recording the differences, and making sure all the variations were documented correctly was intricate work. The typesetting was also difficult because each page needed to include many different fonts, and the proofreading was nerve-wracking.

When it came time to print it, we realized that if we were going to get it printed in book form with a regular printer, we would never have it in time.

Zalman Chanin, the director of Vaad L’Hafotzas Sichos, had the idea to use the printing press in our offices above 770. We didn’t have the facilities to print an entire book, but we could print little pamphlets. He said, we’ll print the books thirty-two pages at a time, and then we’ll just take all those booklets to a binder to get them glued or sewn together.

The 19th of Kislev was on a Tuesday that year, and on the preceding Friday, a bound book was ready and presented to the Rebbe. On Shabbat, the Rebbe came out to the farbrengen holding the new book, and he devoted his first talk to it.

In his talk, the Rebbe explained the point of printing the earlier drafts of the Tanya when we already had the final version: Much could be learned by seeing what the Alter Rebbe originally had in mind, and then comparing it with the final version. Later, the Rebbe actually took the book out, noted some of the differences between the versions right in the beginning of the book, and explained at length why the Alter Rebbe initially wrote one way and then decided to edit it.

The Rebbe also told the story of how, originally, the Alter Rebbe had wanted the first edition of the Tanya to be printed in time for the 19th of Kislev, 1796; before it become the date of his liberation from prison, this was the anniversary of the passing of his Rebbe, the Mezritcher Maggid, in 1772. In practice, however, the book was not ready until the next day. Now, continued the Rebbe, releasing our book in time for the 19th of Kislev was a correction for what had happened in the times of the Alter Rebbe.

From the Rebbe’s talk, it was clear just how proud he was that the project had been completed in time. “Taking into account the tremendous amount of work involved,” he said, “comparing the manuscripts; composing the footnotes, sources and glosses; typesetting, printing and binding; and taking into account that all the people who were involved are limited by the number of hours they are able to devote to this goal; it was impossible for them to be able to complete the printing of this book before the 19th of Kislev!”

“Nevertheless,” he continued, “they worked in a way that transcended all measure and limitation, beyond ordinary human ability… and in this way they completed the printing and binding… even before the Shabbat preceding the 19th of Kislev.” He also gave credit to the instrumental role played by our wives, who supported us throughout the project.

The Rebbe even confided that when he asked us to try and complete the project in time, he had no rational grounds for thinking we would be able to do it. Instead, he had faith, “faith in the power of chasidim, that when they truly desire to fulfill a command, and they decide that it will happen, then they will prevail. That is why I believed that they would succeed.”

The upshot of all this, according to the Rebbe, was that if “human beings were able to work on promoting the teaching of Chasidus with such unbounded haste, despite only being flesh and blood,” then surely G-d must do the same: Bring about the final Redemption with that same unrestrained, boundless haste.

For nearly fifty years, Rabbi Leibel Altein has worked on publishing the Rebbe’s talks as well as the teachings of the previous Chabad Rebbes. Today, he is the director of Heichal Menachem in Borough Park. He was interviewed in August of 2020.