‘Why God Why?’: A Guide for the Brokenhearted

by Yaakov Ort – chabad.org

When Rochel Leah Schusterman, a 36-year-old mother of 11 and Chabad-Lubavitch emissary and teacher in Huntington Beach, Calif., passed away three decades ago, her husband, Rabbi Gershon Schusterman, himself an experienced emissary and community rabbi, felt he needed to be able to understand as never before—and then explain to his children and his community—how it was possible for a loving, all-powerful Creator to take his wife so soon.

The rabbi was far from alone.

A caring, 29-year-old father of three has pancreatic cancer. A teenage girl who has chosen a religious life is diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. A young boy with cancer asks his parents why G‑d is not answering his prayers. A 3-year-old runs into the street and is struck and killed by a conscientious, careful driver. There is one question that is asked in one form or another, millions of times a year, in every corner of the globe when terrible things like these happen to good, innocent people:

“G‑d, how could You let this happen?”

Living a meaningful, productive life often requires a high degree of selective inattention to the tragedies that surround us. When we read accounts of terrible things that happen to others or even hear about them from friends and family, we feel a certain degree of compassion and do what we can to help those who are suffering. That’s very good. But we are built to keep things at a distance, even, or perhaps especially, when your job is to counsel people who are trying to cope with suffering and loss—as is the case with psychologists, social workers and rabbis.

Yet no matter how much training and experience we may have in helping others cope with grief, suffering and loss, it is an entirely different matter when we ourselves, and the people we most deeply love, become the victims of a tragedy that shatters both our world, and sometimes, our connection to G‑d.

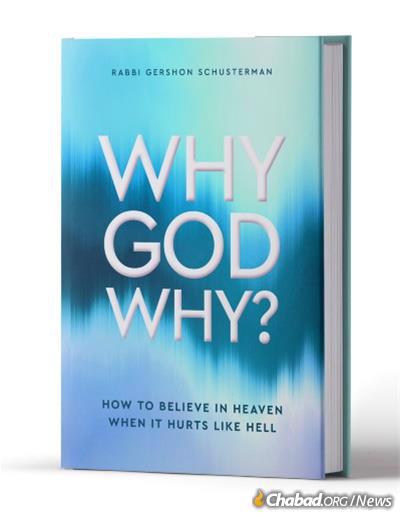

As the result of decades of study, conversation and consultation with experts worldwide following his wife’s passing to illuminate the age-old question, ‘Why do bad things happen to good people?’ Schusterman has written, Why God Why?: How to Believe in Heaven When It Hurts Like Hell (Providence Press). It is an invaluable guide for anyone seeking to maintain and deepen their faith and trust in G‑d when recovering from personal tragedies, as well as for any thoughtful reader seeking to understand better the existence of evil and suffering in a world supervised by G‑d, whose essential desire is for there to be a world filled with goodness, light and joy.

The book brilliantly weaves together classic Jewish philosophy and contemporary positive psychology to give the reader new perspectives on the age-old question of theodicy, the study of the incompatibility of G‑d and evil. Some of the perspectives the author analyzes for G‑d’s permitting the existence of suffering are: The refinement of character, punishment for sin, testing of faith, the result of deeds done in previous incarnations and the idea that ultimately, every bad thing that happens is a Divine decree that will remain beyond the understanding of any human being. While it’s never possible to identify the spiritual cause of any individual tragic event, Schusterman writes, he convincingly demonstrates the value of having a general understanding of each of these often-contradictory perspectives in Jewish thought.

The richly detailed theodicies presented in the book do not appear as dry intellectual exercises but as urgently essential tools in helping people who are coping with loss to navigate the five stages of mourning: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

The author points out that questioning G‑d’s goodness is not only permissible but important, even when done in anger and despair. As he writes:

A human being only cries out passionately to someone with whom that person is truly and intimately engaged. Turning to God, even with a critical and angry tone, brings God into the conversation and opens the door for meaningful dialogue with the Creator.

At the heart of the book is the notion that the perception of evil and the experience of suffering have their purposes, and an ongoing relationship with G‑d is vitally essential to overcome negative feelings and emotions and, wherever possible, to transform them for the good.

Based on everything I have experienced in life, including the traumatic loss of my own dear wife at a young age, and based on all that I have studied and learned to be true, I believe that there is no such thing as an absolutely bad occurrence. How bad something is will depend on our perspective, and that perspective is likely to be limited.

The idea of simultaneously seeing life from both the perspective of man and, to the extent we are able, from G‑d’s perspective, is foundational to Chabad Chassidic thought and a perspective that permeates the book. There is no place where this dialectic is more important than in our approach to the existence of evil. While from our perspective we must see all evil as a challenge to overcome, from a higher perspective we need to appreciate that without evil there would be neither the need for nor the possibility of free will, and thus, no real accomplishment in this lifetime.

Yes, evil does exist, and it is not just the absence of good. Instead, evil is its own entity, one that was put into this world in order to give us the opportunity to fight it. Human beings must do battle against it every day. It may be the most mixed blessing possible in life, because what may be seen as a curse is actually our blessing. Our opportunity—our challenge to override evil—contributes to our life’s purpose. Without evil, we would not have had the ability to exercise our free choice to choose goodness.

Yet for all of the benefits of evil, there is no excuse, or in many ways, there is no explanation for it. In an important addition to the Holocaust literature, Schusterman discusses the question of how a loving G‑d could countenance the quintessence of evil embodied by the Nazis. In approaching this ever-timely challenge to faith, he draws on the perspective of the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory:

The Rebbe was one of the wisest men of our generation, yet even with his staggering level of knowledge and wisdom, he could not offer a definitive response about the reasons for a specific tragedy. The Rebbe affirmed that there is more to human existence and what happens to us than the here and now. There’s also a before and an after. Life’s mysteries, including its tragedies, often defy full understanding while we are still in the here and now. We do know that each soul comes into this world for a purpose, and the soul also lives on after the body’s death. It may go on to heaven and even go through another incarnation. Life in this physical world is just one part of an individual’s total existence. Within our limited frame of reference during this lifetime, the pains and losses we suffer may be doubly painful because we can’t see the reasons for them … so, we perceive them as bad. This may be a new and difficult concept for many people. What we can see and understand in this lifetime is very limited. Much more will be revealed in the Afterlife.

As rooted as we are in this world and this lifetime, no true understanding can come during this lifetime, but only in the next one, presented in fascinating detail in Chapter 9, “The Afterlife: Heaven, Hell and Seeing the Light,” which provides much information and insight about the world to come.

The soul remains aware of its earlier life. The soul retains consciousness of its previous worldly life. It also transitions through stages of realization and refinement, leading to the ultimate enlightenment. By working through these stages, the soul finally sees that which was there all along, hidden in plain sight. This insight, or “heavenly light,” gives the soul a new retrospective awareness concerning what took place during its worldly lifetime.

Since the ultimate answers cannot be provided in this lifetime, we see that the most valuable answer to the question “Why do bad things happen to good people?” is another question: “What can I do now that this bad thing has happened to this good person?” In fact, it can be said that G‑d does not want us to know the answer to the question of why the bad thing happened in the first place.

As we now understand, if this ultimate question about why the innocent suffer were answered, we would be able to make peace with the suffering of innocents. We would no longer be bothered by their cries or feel their pain, because we would understand why it is happening. And that is unthinkable.

Replete with the author’s heartfelt personal reflections, positive anecdotes of those who have successfully coped with tragedy and loss, and the timeless wisdom of Chassidic masters from the Baal Shem Tov to the Rebbe, Why God Why? is an extraordinarily accessible contribution that is sure to provide an invaluable perspective to every reader interested in developing a deeper connection with G‑d and the world under even the most difficult circumstances.

“Why God Why?: How to Believe in Heaven When It Hurts Like Hell” is available for purchase online from Kehot and at Jewish bookstores.

Levi Bukiet

its an awesome and mind provoking book. A true academic rollercoaster. Real, Truth and real Life struggles and pain. A must read for all during these difficult times we live in.