Legendary Buffalo Campus Rabbi’s 50 Years on the Job

by Mendel Super – chabad.org

He would go wherever the Rebbe sent him, the young Chassid told his Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory. It was 1971. Twenty-five-year-old Rabbi Nosson Gurary had been married for two years and now wanted to join the growing number of Chabad-Lubavitch emissaries around the world. The Rebbe pointed him to Rabbi Chaim Mordechai Aizik Hodakov, his chief-of-staff and director of Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch, the educational arm of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement.

The first suggestions—Finland, Greece, Denver and Houston—all fell through for different reasons. At the same time, residents of Buffalo, N.Y., had reached out to the Rebbe’s secretariat, expressing concern about the lack of Jewish life on campus and how that void was being filled by Eastern religions, radical politics, cults and drugs.

“The place was going haywire,” Gurary recalls in an interview with Chabad.org. “There were thousands of Jewish students, and they were turning to the hippies for meaning and direction. The Vietnam War was raging, and riots were happening almost daily. Bombs were exploding on campus.”

Gurary accepted the position as director of the Chabad House of Buffalo—one of the very first Chabad Houses on campus—and had a private audience with the Rebbe, together with his late wife, Miriam, and their eldest child, Avrohom. “I had questions for the Rebbe. What do I answer when people ask how Jews are different from non-Jews, and when people ask my position on the war?”

The Rebbe answered the first question with an analogy: When building a house, everyone is needed, from the architect to the plumbers, electricians and carpenters—all are equally important in getting it done. But everyone needs to know their talents; if each person doesn’t carry out their specific task, the house won’t be built. In this world, the Rebbe said, everyone is here to make it a better place; we’re all in it together, but each has their own mission.

With the divisiveness and violence that Vietnam was bringing, the Rebbe told Gurary that the young rabbi should stay away from such questions, for one can only answer if they understand the issues involved and in this case, the Rebbe said, the issues surrounding the war were complex and unclear—advice that would serve Gurary well in those turbulent years.

First Encounters on Campus

Gurary’s first encounter on campus made him question if this was the place for him. He approached a young hippy-looking man and asked if he was Jewish. The student became so outraged by the very question, which to him implied a lack of equality, and told the rabbi that if not for the respect he had for his father—who taught him to always have respect for rabbis—he’d punch Gurary in the face.

But the young rabbi couldn’t be scared off. “The whole mindset was that we are only here to save these young Jews from assimilation and apathy. We had to be successful; our lives were on the line. This wasn’t a job; it was about Jewish souls.” Gurary remembers bringing renowned American literary critic and Buffalo English professor Leslie Fiedler to Brooklyn for an audience with the Rebbe. When he left the Rebbe’s room, “he was red like a beet,” Gurary recalls. “ ‘I just came down from Sinai,’ he told me. The Rebbe told him that there’s a house on fire, and we must save as many people as possible.”

Meryl Dalvin recalls that first year well. “As I was walking just 500 meters from my apartment, I saw a door with a picture of two Chassidim dancing,” she told Chabad.org from her home in Israel. Curious, she knocked. “Who are you and how did you get here?” she asked the bearded man. “It was Rabbi Gurary, and I was his first customer. I was sold before he even opened the door.”

Dalvin grew up in Brooklyn and was quite familiar with Judaism. She’d just come back from a trip to Israel, an experience which had made her rethink her religious life. “It was dramatic. As a result of the trip, I decided to become religious.” She committed to keeping Shabbat and kosher, and “regretfully” returned to Buffalo, not sure how practical it would be to lead her new life on campus. “I was sent for him and he was sent for me,” she muses.

“Rabbi Gurary didn’t get the degenerated culture of the time,” says Dalvin. “Nothing stopped him.” She recalls a tefillin stand he set up on campus, right next to another stand hawking ideas that were an affront to everything the rabbi stood for. Gurary wasn’t fazed. Instead, he asked the student staffing the table if he was Jewish, which he was. Gurary struck up a conversation and gently noted that this wasn’t fitting for a good Jewish boy. “If you were Jewish, he would let you know what that means,” says Dalvin. “His innocence charmed everyone; there was no falseness in him. These were rebellious students, full of anger, but he was beyond that. It was recognizable that he was totally honest and true to his beliefs.”

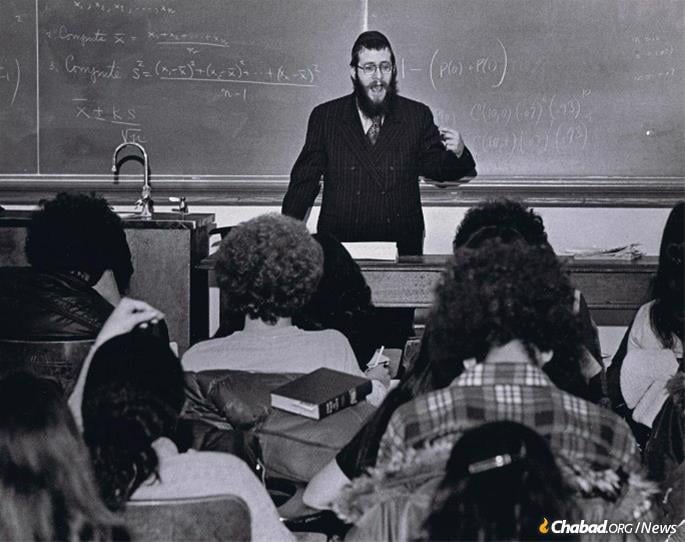

From when she met Gurary, Dalvin went to Chabad every Shabbat and attended every class. The classes were all accredited, and students were tested and graded on the material. The impetus to deliver classes this way likely came from the Rebbe himself.

“Early on, I got a call from headquarters,” says Gurary. “It was Rabbi Hodakov on the line. ‘Don’t give any classes that aren’t for credits,’ he instructed me.” Gurary wrote up a résumé detailing his achievements including advanced rabbinic ordination, which the university accepted as an equivalent of a master’s degree, published a paper and “by miracle” was approved to give accredited classes. “From year one, I gave three classes: Jewish mysticism, Chassidic philosophy and Chassidic music.” The latter attracted many music students. “I had a mob of students coming. Once they came for the credits, many became involved in Judaism in a deep way.”

Gurary served for decades as an adjunct professor in Judaic studies at the State University of New York (SUNY) and adjunct professor in the State University Law School, both in Buffalo. His teaching eventually also led him to earn a Ph.D. in philosophy, gained long-distance via Moscow State University.

In his capacity as a law professor at the State University Law School, during the early 2000s, he invited the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia to speak at the law school. Scalia in turn introduced the rabbi to his Jewish colleagues Stephen Breyer and the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg, with whom he’s maintained a relationship for years.

That relationship led to Gurary hosting a dinner at the Supreme Court to launch his National Institute for Judaic Law.

“Eventually, we offered 20 different courses on a huge variety of subjects,” he recalls, noting how the courses became a central part of Chabad’s work on campus.

As for Dalvin, by the time she returned home she had become a Chassid and her parents were aghast. “They said I had joined a cult,” she remembers.

“It’s under the leadership of Rabbi Schneerson,” she countered. That suddenly changed everything. “If it’s Rabbi Schneerson, it’s OK,” Dalvin’s mother said in an about-face. Unbeknownst to Dalvin, when the Sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory, arrived in New York from war-torn Europe, her grandfather would attend his farbrengen gatherings at 770 Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn.

A Generation Searching for Meaning and Truth

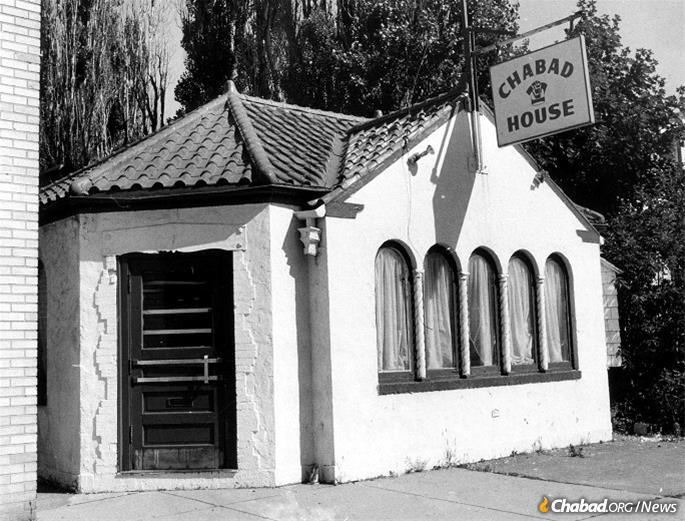

The very elements that made the ’70s a challenging decade may have been what pushed people through the doors of the small Chabad House on 3292 Main St.

“They were searching for the truth,” says Gurary. “They were thinking people, and they were fighting the establishment; they knew something was wrong. Unfortunately, the last place they would go to was Judaism.”

It was the commercialized, institutional Judaism in America during the 1950s and ’60s that created a generation that wanted nothing to do with the religion of their parents, Gurary feels. “They didn’t know the religious aspect of Judaism, just the lavish bar and bat mitzvahs. They sold the world the Brooklyn Bridge,” he explains. “You want your child to be ‘bar mitzvahed?’ You have to join a congregation, and the Hebrew school will teach him the Haftorah. It’s malarkey; there is no requirement that a bar mitzvah boy needs to read a Haftorah.”

That example, he says, was symptomatic of a broader, systemic approach: Judaism was confined to grandiose structures devoid of its spirit and soul. “The whole emphasis of the education wasn’t to teach these kids their religion. They weren’t taught about Torah and mitzvot. After the party, the child had no respect for his religion, it wasn’t taught.” If anything, he says, those bar mitzvahs were a turn-off. “How could you blame them for looking to other religions or intermarrying? They weren’t taught about the Jewish soul.”

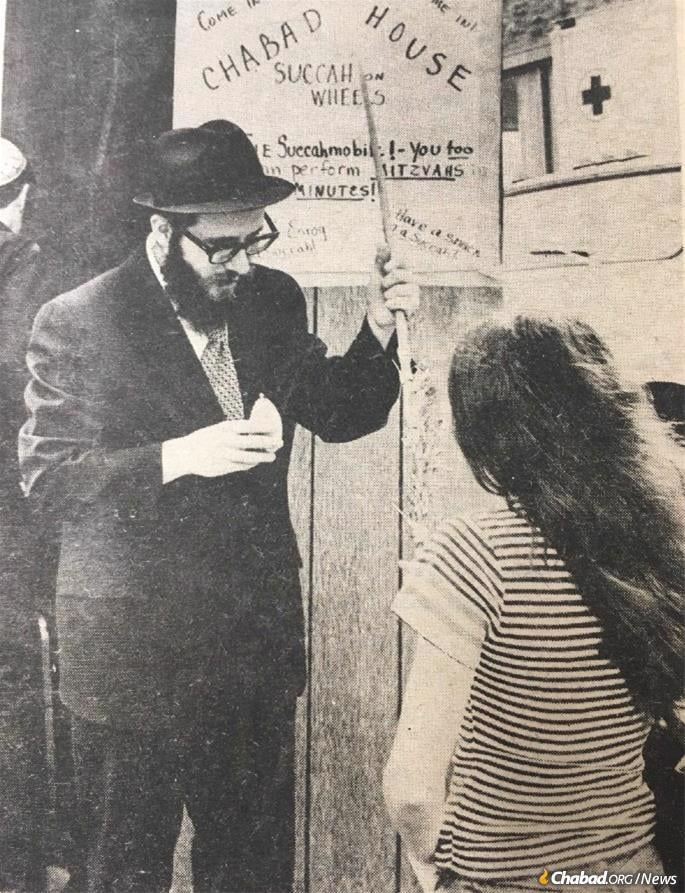

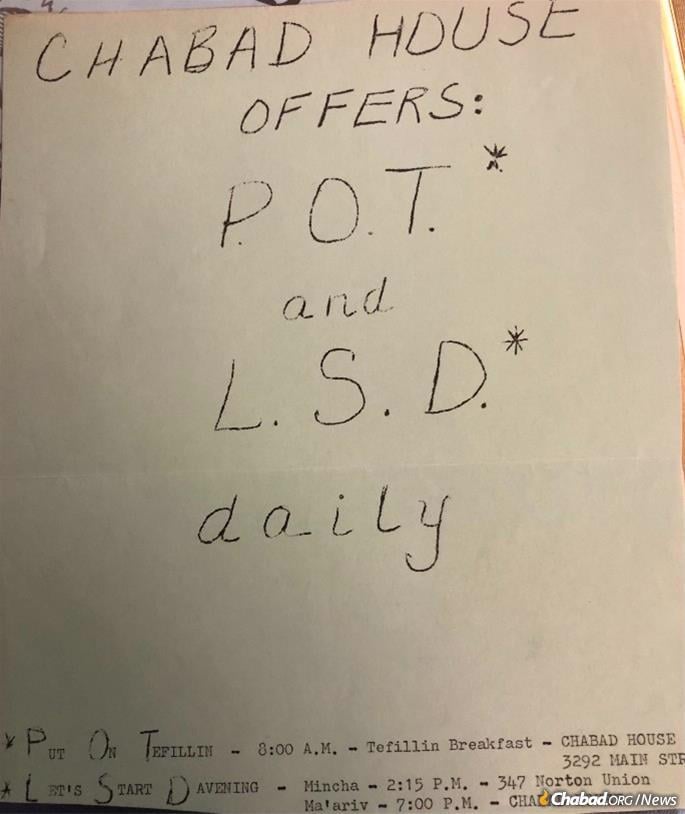

When students encountered Chabad on campus—often through Gurary’s persistence and creativity, such as signs hanging in the unions reading “Chabad House Offers: POT* and LSD* Daily” with a footnote below explaining that “Pot” was “Put On Tefillin” every morning at 8 a.m. and “LSD” meant “Let’s Start Davening”—they indeed got hooked, but on a substance that mattered: Judaism.

Gurary didn’t need the pricey marketing strategies and membership plans of the large congregations that failed to engage his students before they went off to college. All he had was his persona, authenticity and love—and large poster boards and colorful markers.

The rabbi rejects calling them gimmicks. “The only gimmick we had was genuine concern and love. We never gave up. It wasn’t easy getting rejected but you stomach it. We always called again.”

Drawing Students to the Rebbe’s Mitzvah Campaigns

Student by student, things began to change on campus. It was personal, one-on-one conversations, classes and late Friday-night discussions that turned the tide. “When I would talk to a student, I would tell them, ‘You are Jewish, there’s nothing you need to do, you have it all,’ it was a new world for them. You just need to bring it out, and how? ‘Mitzvahs! Mitzvahs!’ ” Gurary exclaims. “Your personal connection to G‑d; it starts now. It’s not about the afterlife; it’s right now.”

The Rebbe’s mitzvah campaigns—wrapping tefillin, blessing the lulav, and other quick, easy mitzvahs—ubiquitous today but rather novel then, gave a structure for engaging students in meaningful Judaism before they even entered the Chabad House. “The mitzvah campaigns were such an incredible idea,” says Gurary. “They gave students an experience that connected them with G‑d. Not one minute, but an eternal moment. Kids just never heard of this before: G‑d, the neshamah (“soul”)—it was all foreign to them.”

Gurary pioneered what has become the ubiquitous Chabad approach to Jewish outreach—a proactive attitude and the goal of meeting people where they are at. “From day one, we reached out. We never waited for students to come to us.” The majority of students, he says, weren’t looking for more Judaism in their lives. “I went to the dorms, I went to the bars—wherever they were. We’d invite them for Shabbat dinners, holidays; we were constantly reaching out.”

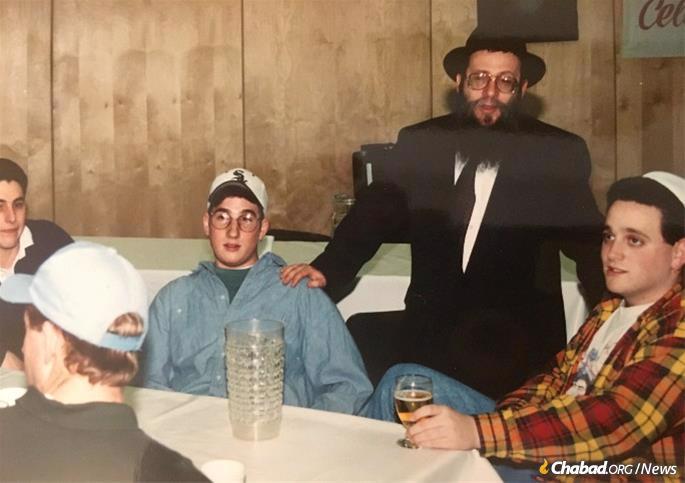

Andrew Livingston, today a Manhattan businessman, will never forget that Shabbat morning in 1991 when Gurary marched into his dorm room. “He knew where we were. He came in to wake us up. None of us complained, we all went to Shabbat services happily and hung over.”

Perhaps owing to his sobriety, Gurary remembers his encounter with Livingston more vividly. “I went into the wrong dorm room. A guy had a cover over his head, I thought I knew who it was. ‘Get up! Time to come to Chabad to pray!’” The guy stirred. “He was a long, tall guy. Basketball player look. I got so scared that I woke the wrong guy. Turns out, he was Jewish, and he said he would come. We gave him an aliyah, he stayed for lunch and he became a regular.”

“He actually bar mitzvahed me that week,” remembers Livingston. “I received my Hebrew name, Avraham. It’s something I’ll cherish for the rest of my life. He cared so much about us; he was a mentsch. It renewed my faith in Judaism.”

Growing up in Surrey, England, Livingston says he didn’t have much exposure to his heritage until he connected with Gurary. “From that point on, it’s been in my life. Chabad was fun! I took the rabbi’s classes, and he took an interest in my life. They had huge catered Shabbat meals; we prayed and partied. In Buffalo in the middle of the winter, there wasn’t much going on. Chabad was a home away from home and always well-attended.”

In the decades since he graduated, Livingston notes that “Chabad has continued to be a part of my life, anywhere in the world.” When Chabad rabbinical students began visiting his Manhattan office weekly, like they do with many offices and streets in New York and other cities, he connected with them immediately, putting on tefillin with them and discussing the weekly Torah portion. Frequently, he treats them to dinner at a kosher restaurant. “The Chabad guys are so chill, they help me stay connected.”

An Unlikely 10th Man for a Yom Kippur Minyan

Gurary’s trademark charisma and charm brought in students who would have never come on their own. He recalls one memorable tale, of the many at the tip of his tongue.

“One Yom Kippur, the university was closed. We stayed open, as we felt there should be something for those who stay behind. But would we get a minyan? It would be a disaster if we didn’t.” Gurary knew what he had to do. He went to a Jewish fraternity leader and told him: “Tomorrow is Yom Kippur. I need you to send me nine guys for a minyan.”

Sure enough, at exactly 10 a.m. the next morning, in marched nine men. He had his minyan. “I led the service. During the Amidah, I hear the door opening and closing. When I finished, I turned around, and the room was empty. They’d all gone.” The rabbi wasn’t having any of it. Wrapped in his tallit and kittel, he marched through the campus looking for them. “I found them watching a ball game. ‘How could you leave in the middle of the service?’ I asked them. They all came right back with me and stayed until the end of the service.”

They promised to come back for the mincha prayer and stay until the end of the holiday. But as the sun began to set, only eight of them were there. Desperate, the rabbi told them to stay put and ran to the cafeteria, hoping to find a Jewish boy. “He was sitting there eating; he had such a sweet, Jewish face.” Gurary convinced him to come and complete the minyan, and the student agreed after he’d finished his meal. “I waited 20 minutes with him watching him eat his non-kosher food on Yom Kippur.” But he came, and stayed for the break-fast meal at the conclusion of the holiday. “This boy, who didn’t know it was Yom Kippur, ended up at the yeshivah in Morristown, N.J. and became observant,” says Gurary. “Never give up on anyone.”

From Student in Buffalo to Emissary in Safed

Rabbi Mordechai Siev, better known as Big Moe, went to Buffalo from 1976 to 1979. He says he didn’t show much interest in Judaism until college. “I grew up on Long Island, my family wasn’t religious. We went to a Conservative congregation on the holidays, like many on Long Island,” he says. “In my sophomore year at Buffalo, I experienced some antisemitism. I had a reaction: I began to wear a Jewish star, I wanted to tell everyone that I was Jewish.”

Soon, friends told him about the Chabad House on Main Street, and together with a group of friends, he came one Friday night “for the free meals,” he quips. “We met Rabbi Gurary, and we became part of the community.”

“That was the beginning of my connection. I started to feel more Jewish.” Gurary asked the tall, muscular Siev to accompany him on his Shabbat morning trips through the dorms, wanting to avoid trouble. “We went room to room, it was quite something to see him in action,” recalls Siev. “He would knock on a door if he knew there was one Jewish student in the room. He didn’t know what would be with the three others. He’d walk in, these guys would be sitting on the floor drinking or smoking pot, he’d sit down next to them and ask, ‘What’s your Jewish name?’ He connected with so many people that way,” says Siev.

“I remember one Rosh Hashanah we walked from Chabad to the campus. The rabbi got up on a table and announced to the students that it was Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and blessed everyone.” Then Gurary blew the shofar and invited everyone to the Chabad house for lunch. “All these experiences were quite amazing. I never saw Judaism like that. At our congregation on Long Island, you walked in, put on a kippah and removed it as you walked out.”

One Friday night, as Siev and a friend stood outside the Chabad House talking with Gurary, a car drove by. The windows rolled down, and out came “Heil Hitler! We didn’t finish the job!” “Rabbi Gurary looked at us and said, ‘You guys aren’t going to do anything?’ ” Then the car spun around and someone inside yelled “Turn on the ovens!” Siev gave chase, catching up at a red light. “I snapped off the antenna and scrawled a Star of David on the hood.” A brawl broke out in the street, and the police came. They wanted Siev and his friend to accompany them to the station, but Gurary insisted that it was Shabbat and they weren’t going anywhere. The police acquiesced and arrested the antisemitic hooligans.

That’s when Mordechai Siev was transformed to “Big Moe,” a moniker he still goes by today as a Chabad emissary in Safed, Israel, where he serves as outreach director at the Ascent center.

Staying in Touch

At one point, when the going got tough and covering the budget was increasingly difficult, Gurary wrote to the Rebbe. “I told the Rebbe that I am considering leaving for a position where I wouldn’t have to fundraise.” But the Rebbe didn’t accept his resignation. “Thousands of students have come closer to Judaism through your courses,” came the Rebbe’s response. “How can you consider leaving?”

Not only did Gurary stay, but he also spearheaded an entire Chabad network in the city and the broader region—from a day school in Buffalo to Chabad centers on campus in Binghamton, Rochester, Syracuse and Ithaca.

Today, Gurary focuses his efforts on the alumni, many of whom he’s still closely in touch with. He also gives regular online classes to them, which are joined by alumni from all over the world. His children—Rabbi Avrohom and Chani Gurary, and Rabbi Moshe and Rivka Gurary—led Chabad at Buffalo into the last decade and continue their father’s tradition of warmth, care and genuine love for every student.

Shely Finberg, 24, graduated from Buffalo in 2019. She’s an American-Israeli and says that many Israelis tend to stay away from religion outside of Israel. She thought she would, too, but she ended up rooming with an American Jew who told her “We have to go to Chabad; my mom wants me to go.” Finberg was apprehensive, but she went along. “Rivka Gurary is Israeli, and we connected right away. I never stopped going—I would walk through the rain and snow to go, I didn’t care. When I was sick, they helped me. When I needed advice, they were there. When I needed community, family, they were my family away from home,” she says.

Finberg says she took advantage of everything Chabad offered—from the Sinai Scholars classes and women’s classes to their trip to Poland. “I staffed the Birthright Israel trip, I went to [Chabad’s] Key Largo trip, and though I graduated in 2019, I’m always looking for more things to do with local Chabad centers.”

After a difficult breakup in a relationship, Finberg turned to Rivka Gurary for a listening ear and a shoulder to lean on. “Rivka helped me get through it,” she attests. Following that experience, Finberg came to a deep, personal realization.

“I don’t know if I’ll ever keep everything,” she admits candidly, “but what Chabad taught me was how much I want to marry Jewish and how badly I want to have a Shabbat meal with my own family.”

More than 50 years since the Rebbe first sent Rabbi Gurary to Buffalo, Chabad is still there reaching out to each and every Jewish student on campus. Never giving up on anyone.