Memo to Secret Police Chief Reveals Hunt For Chabad’s Soviet Underground

by Dovid Margolin – chabad.org

On June 6, 1950, Maj. Gen. Mikhail Popereka, a deputy minister of the Ukrainian branch of the MGB Soviet secret police—the precursor to the KGB—drafted an 11-page memo on the status of the ongoing investigation into the case of the “Chassidim” and sent it to Viktor Abakumov, minister of state security (MGB) of the Soviet Union. Marked with a hand-written “Top Secret,” the report synopsized information gathered by the MGB over the course of its investigation into “the Schneerson anti-Soviet organization” via foreign agents, informants and interrogations. An anti-Soviet center headed by the “tzaddik Schneerson”—standard shorthand for the Sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, of righteous memory, in Soviet documents—had been set up in New York by American intelligence under the guise of a yeshivah, a European branch established in France, and all of it connected to an extensive anti-Soviet network within the Soviet Union. This, at least, is how the Soviet Union’s intelligence apparatus saw it, all the way to the top.

At the time that he received this memo, Viktor Abakumov was one of the most powerful men in the Soviet Union. A member of a younger generation of Communist Party cadres wholly devoted to Stalin, he joined the secret police at age 24 in 1932 and rose through the ranks to become a top deputy to the notorious Lavrentiy Beria, head of the secret police and a close confidant of Stalin. In 1943, Abakumov was appointed the head of the newly formed SMERSH (a Russian acronym for “Death to Spies”), Stalin’s particularly brutal, war-time military counter-intelligence organization, and began reporting directly to Stalin. At no point was Abakumov above personally torturing his captives. After the war, in 1946, SMERSH was merged into the secret police and Abakumov, by then one of Stalin’s favorites, was promoted to head of the MGB. “For the next five years, Abakumov was in control of the life of almost every Soviet citizen and his MGB could arrest any citizen it chose—without waiting for an order from Stalin,” Vadim J. Birstein writes in his comprehensive SMERSH: Stalin’s Secret Weapon. “Through the MGB branches in occupied countries, Abakumov also controlled half of Europe.”1

In other words, the danger posed by the “Chassidim,” a term used interchangeably with “Schneersonite” in Soviet secret police documents, to the state security of the Soviet Union and perhaps the fate of Lenin’s revolution itself, was of concern to literally the highest echelons of Soviet power.

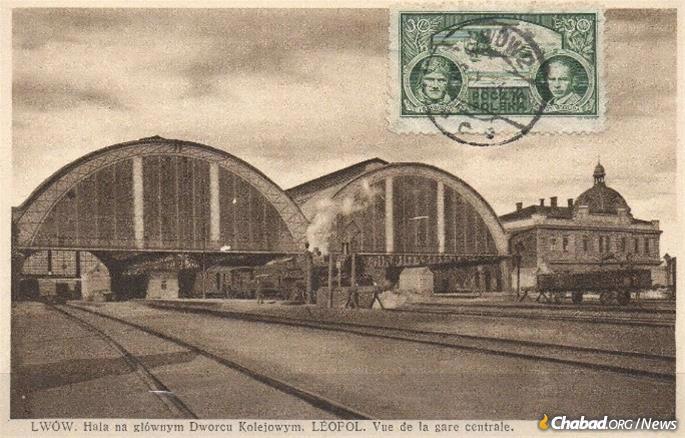

The report to Abakumov, presented below in its original form and for the first time in English, focuses on the aftermath of what is today known as the Great Escape, a sophisticated and dangerous operation conceived and executed by Chabad-Lubavitch Chassidim to illegally escape the Soviet Union after World War II. With the Sixth Rebbe’s blessings, beginning in the spring of 1946 and concluding on New Year’s Day 1947, approximately 1,200 Lubavitcher Chassidim procured false or doctored Polish citizenship papers and fled the Soviet Union via the Ukrainian border city of Lvov (today Lviv).2 The last successful crossing took place on Jan. 1, 1947 (9 Tevet, 5707), after which, as mentioned in the document and in more detail in histories of the Great Escape, the remaining organizers of the operation were hunted down and arrested.3

But the main focus of this MGB memo is a second, far less known Lubavitcher attempt to flee the Soviet Union en masse through Romania. The plan was tested in December of 1948, when four Chassidim—Moshe Chaim Dubrowski, Meir Junik, Yaakov Lepkivker and Moshe Greenberg—left the city of Chernovtsy, Soviet Ukraine, less than 40 kilometers away from the border, and smuggled themselves into Romania.

This time, the results were tragic.

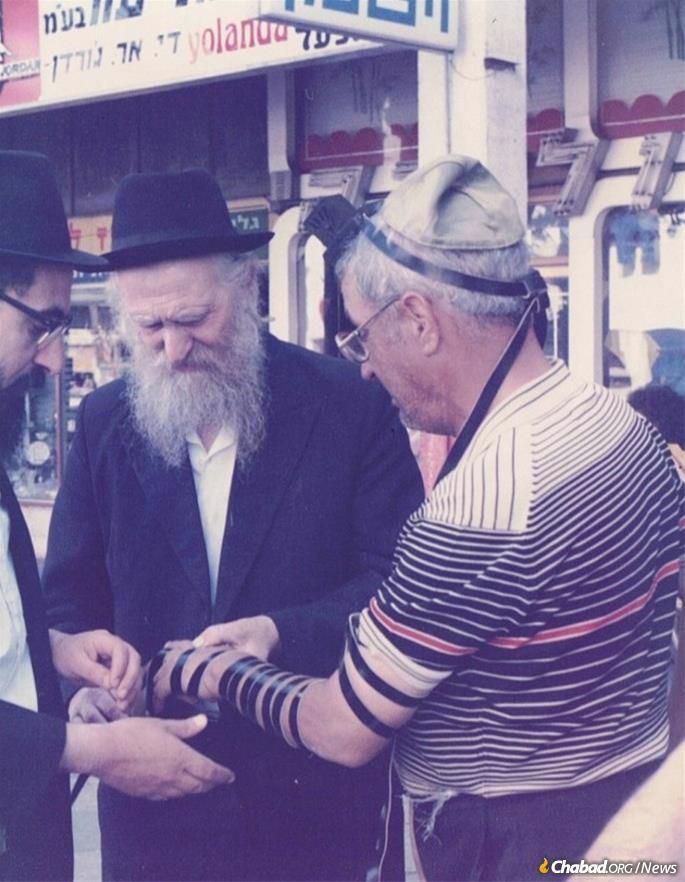

The Background: Post-Holocaust Polish Repatriation

From the start of the Bolsheviks’ war on religion, the Sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak, led the Jewish resistance. For this work, he was arrested in the summer of 1927 and initially condemned to death. His sentence was first commuted to 10 years of hard labor, then three years of exile, and finally, on the 12-13 of the Jewish month of Tammuz, full release. In October of 1927, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak was forced to leave the Soviet Union “but not before he had trained many teachers whose influence was felt in the USSR long after his departure.”4 Through the absolute hell of the 1930s, Lubavitcher Chassidim continued to risk their lives to maintain Jewish life and learning in the Soviet Union, as they’d been charged by the Sixth Rebbe. Many, including Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson—father of the Seventh Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, and until his 1939 arrest the chief rabbi of Dnepropetrovsk, Ukraine—paid the ultimate price.5

With the outbreak of World War II, a sizable portion of the Chabad-Lubavitch community escaped the German onslaught and local collaborators’ zeal by evacuating to Tashkent and Samarkand, in Soviet Uzbekistan. There, joined by tens of thousands of Jewish refugees from the USSR and Poland, they recreated Jewish life, opening yeshivahs, building mikvahs and praying together in synagogue. The Lubavitcher Chassidim did not just care for themselves but actively recruited Jewish children to study Torah, many for the first time in their lives. The children, who were cared for materially as well, drew from the widest background, including Bukharian locals, Polish refugees and members of the Soviet nomenklatura. Among their students was even a 16-year-old relative of Stalin acolyte Lazar Kaganovich.6 This is how the memo to Abakumov describes this period: “According to SCHNEERSON’s directives, the Chassidim intensified their anti-Soviet activities and created illegal schools in the cities of Samarkand and Tashkent, in which Jewish youth who fell under their influence studied in a religious and nationalist spirit.”

The war years in Uzbekistan were by no means easy, with the secret police continuing to operate, and adults and children dying from privation and diseases. Nevertheless, this was a relative period of peace for the beleaguered Chassidim of the USSR. With the end of World War II, however, it became clear that this situation would not last for much longer. That’s when a rare opportunity to escape the Soviet Union first presented itself.

Just a few months after the war, on July 6, 1945, the Soviet Union signed a treaty with the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland agreeing on a population exchange. Ethnic Russians, Ukrainians, Belorussians and Lithuanians would have their Polish citizenship exchanged for a Soviet one, while ethnic Poles and Polish Jews who now found themselves in the Soviet Union would be repatriated to Poland. “A secret instruction of December 1945 specified that Poles and Jews (i.e., not Ukrainians and Belorussians) who had lived on the territory of Poland up to September 17, 1939, might return from the USSR.”7 This meant that even eligible individuals who’d formerly been residents of the eastern half of Poland, which in the aftermath of the Hitler-Stalin non-aggression pact has been annexed by the Soviet Union (and to this day is a part of Belarus), could renounce their unilaterally granted Soviet citizenship and return “home” to Poland.8

Special joint Polish-Soviet committees were established to facilitate this repatriation, and as 1946 progressed, ever larger numbers of people were granted permission to leave. Many traveled to Poland in separate cars attached to regularly scheduled trains. Albert Kaganovitch estimates that over the duration of 1946 about 147,000 Jews were allowed to leave the USSR in this way. This might appear generous on Stalin’s part, but the truth was the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland, formerly called the Lublin Committee, was a pro-Soviet puppet entity that Stalin was using to outflank the Polish government-in-exile in his plan to transform post-war Poland into a Communist satellite state. Whatever Stalin’s reasons were for allowing Jews out, the fact remains that Polish repatriation presented a limited window of opportunity to leave the Soviet Union.

The Lubavitchers in Central Asia and other places of evacuation throughout the Soviet Union had for the duration of the war lived side by side with Polish Jewish refugees. Now the Polish Jews were heading to Lvov to be repatriated back to Poland, from which they could go on to Mandatory Palestine, the United States or other countries in the West. As Soviet citizens, the Lubavitcher Chassidim were ineligible to leave, but by the end of 1945 the idea of somehow taking advantage of this window was percolating.9

The Great Escape From Lvov to Poland

In the beginning of 1946, a 22-year-old yeshivah student named Leibel Mochkin arrived in Lvov to scout out the town. With the help of his older brother, Shmuel (Mulle) Mochkin, and former Latvian-Jewish parliamentarian Mordechai Dubin, by then in Moscow, he connected with the chairman of the Lvov Jewish community, who in turn opened doors necessary for the operation’s success.10 The first trickle of Lubavitchers arrived in Lvov in the spring of 1946 and slowly began crossing the border. Their success encouraged others. As the months went by more and more Chassidim arrived in Lvov, abandoning their jobs, homes, furniture and any other immovable wealth for the chance to get out.

“The situation was becoming desperate, with a severe shortage of food and accommodation,” Moishe Levertov recalled. “Officially, as elsewhere in the Soviet Union, it was illegal to stay in the city for more than 24 hours or to receive food coupons without being registered as a resident. To obtain registration papers, one needed a work permit. Worst of all would be if anyone were stopped by a policeman without appropriate documentation. Since the situation was so dangerous, everyone clamored to be on the first [train] that would become available.”

It was no longer a matter of procuring a handful of false passports, but hundreds, and a larger and more complex escape infrastructure quickly came together. Its leaders learned to doctor passports, arranged phony marriages, and of course bribed necessary officials, including those who worked at the train station and officers of the local MGB.

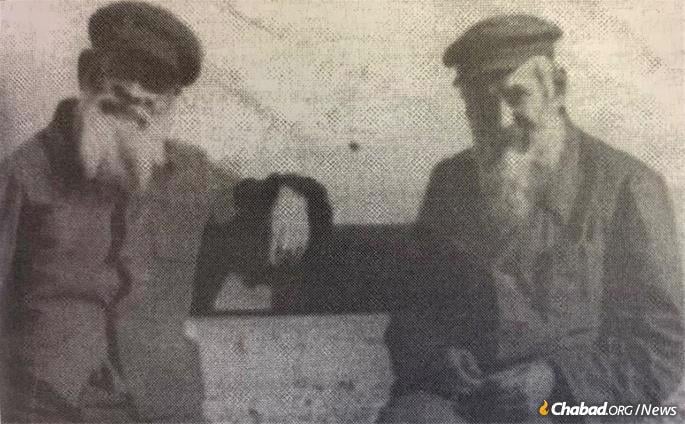

With matters of life-and-death at hand, a specially formed rabbinical court of 23 judges was convened.11 The judges12 determined that everyone participating in the operation had to contribute whatever money or valuables they had to the pot to assist as many people as possible to leave. One of the members of the smaller operating committee leading day-to-day operations (as well as a member of the rabbinical court) was Moshe Chaim Dubrowski, whose story we’ll return to shortly. Dubrowski’s grandson, Berel Dubrowski, was about 17 or 18 at the time.

“I didn’t have a beard yet [and therefore less conspicuous], so I was sent to collect money from people … ,” recalls Dubrowski, 94. “I remember one time I needed to pick up money from someone. How do you do it? We made up he’d be sitting in the park on a bench holding a particular newspaper with a briefcase next to him. I came up to him and we exchanged briefcases, his was filled with cash, and mine had more newspapers.”

He was at various times also charged with distributing forged Polish documents. Once he was tasked with arranging a truck to bring a number of families to the train station in the middle of the night. Things nearly went south when the truck headed to the wrong place, leading to a Soviet sentry overhearing a member of the group speak Russian, a red flag that they weren’t in fact Poles. Dubrowksi followed the sentry into his post. “I asked him: ‘How much do you want?’ and he said ‘700.’ I told him, here, I have 300 in my pocket, 200 for you and 100 for your friend,’ he said ‘Okay.’ ”13

Leibel Mochkin was in charge of arranging fake Polish passports, Kahan and Futerfas handled the money, and the elder Dubrowski dealt with various emergencies. Another active member of the smaller operating committee was Tzipa Kozliner.14 Ultimately, combining Divine assistance, cunning, wits and a healthy dose of bribes, the operation successfully transplanted the nucleus of the surviving Lubavitcher community from Russia, where it had always been, to the West and Israel. That the transports were made up of visibly Chassidic men, women and children, none of whom spoke a word of Polish, is all the more startling.

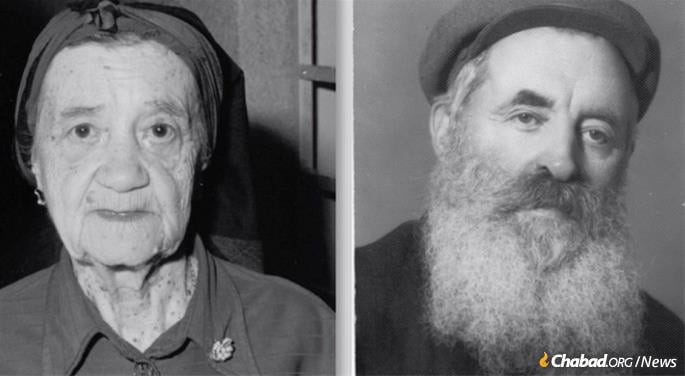

By far the most prominent person brought out of the Soviet Union in this way was the Rebbe’s mother, Rebbetzin Chana Schneerson, who smuggled her late husband’s precious writings out with her.15 The single largest illegal transport arranged by the Chassidim from Lvov left on Dec. 2, 1946 (9 Kislev, 5707), all together numbering 232 people.16 Kaganovitch estimates that only about 1,500 Soviet Jews escaped illegally using false Polish documents during this period. The vast majority of them were Chabad Chassidim.

In Poland, the Chassidim connected with members of the underground Bricha (B’riha), a Zionist organization that smuggled Jewish Holocaust survivors into British-controlled Palestine. “The B’riha men were amazed at [the Lubavitchers’] ingenious escape from Russia and deeply impressed by the discipline, the sense of solidarity and the reverence for their Rebbe in New York which held the Hasidim together,” recalled former Bricha commander Ephraim Dekel. They were secretive, he notes, and cooperated with the Bricha strictly on their own terms. “The ‘Lubavitchers’ were, in fact, running an underground network of their own … .”17

Among the Chabad leaders arrested in the operation’s aftermath were Mendel Futerfas (arrested on the train leaving Lvov in 1947, released from the Gulag in 1956); Yona Kahan (“Poltaver,” arrested in 1948, died in the Gulag in 1949); and Mordechai Dubin (arrested in 1948, died in Soviet custody in 1957). Not named in this memo but arrested on the same train as Futerfas was Shmuel Notik (“Krislaver”), previously a beloved Chassidic mentor in Chabad’s underground yeshivahs throughout the USSR, who perished in the Gulag in the beginning of 1949.18

The Second Attempt: The Chernovtsy-Romania Plan

Following the end of the Great Escape, a number of Chassidim decamped to the city of Chernovtsy, Soviet Ukraine, which prior to 1940 had been a part of Romania, and before that the regional capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s Bukovina region.19 Though now firmly within the expansionist borders of the Soviet Union, Chernovtsy was still close to the Romanian border, and Chassidim who had been involved in the initial escape through Lvov, namely Moshe Chaim Dubrowski, Moshe Vishedsky, Chaim Zalman Kozliner, Asher Sossonko and others, had heard it was feasible to illegally cross from there into Romania. This was by no means a fantasy. Between February and April 1946, 22,307 Jews illegally immigrated from Chernovtsy province into Romania, a process authorized by Stalin himself and organized by Soviet authorities. “… [T]he decision was not motivated by concern for the suffering of the Jewish population,” the historian Mordechai Altshuler notes. “Rather the decision appears to have been primarily influenced by consideration for the hostility of the local population toward the Jews [returning to their homes and towns following the Holocaust] and the general tendency to Ukrainize areas that had been annexed to the Soviet Union.”20

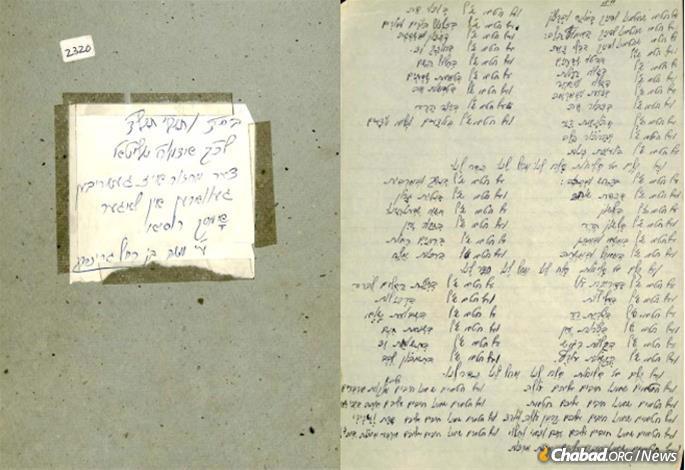

The Chernovtsy-Romania pipeline appears to have remained viable past the middle of 1946. In July of 1947 Chassidim in the USSR sent a coded message21 to Yitzchak Goldin, a Lubavitcher escape coordinator based at the time in Prague, Czechoslovakia, laying out the idea and requesting that someone be sent to Bucharest, Romania, to help coordinate an escape from the other side of the border.

Ultimately, a young Moscow-born yeshivah student named Zalman Abelsky was dispatched to Romania. Like most Lubavitcher Chassidim in Europe at the time, Abelsky had escaped the USSR via Lvov in 1946, and his starting point was the Displaced Persons camp in Pocking, Germany. He headed first to Prague where with the Bricha’s help he crossed into Austria. It proved impossible to move further so he returned to Czechoslovakia and from there crossed illegally into Hungary, reaching Romania months later. There he connected with the Skulener Rebbe, Rabbi Eliezer Zusia Portugal, who directed a network of orphanages for Jewish children in Bucharest and served as a heroic Jewish leader in Communist Romania. Abelsky was also aided by Yaakov Griffel, a war-time Orthodox Jewish activist who represented the Vaad Hatzalah, Agudas Yisrael and the Central Orthodox Committee. The MGB memo prominently mentions both the Skulener Rebbe and Griffel.

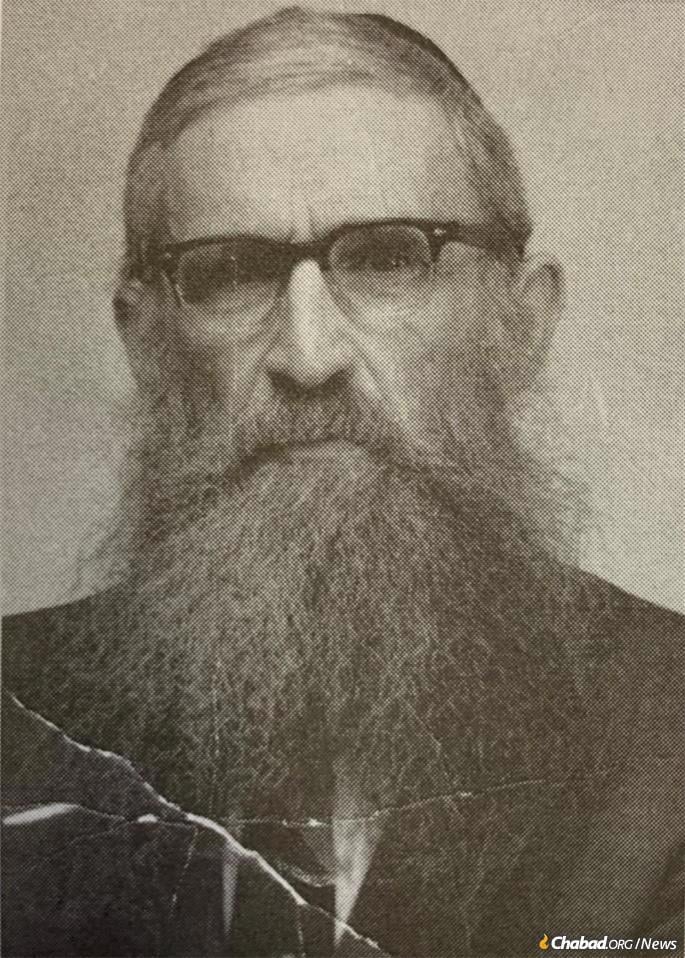

In December of 1948, 17 months after the idea was first broached, three young yeshivah students—Meir Junik, Yaakov Lepkivker and Moshe Greenberg—set out over the border into Romania with the intention of testing out the escape route before a larger-scale flight was attempted.22 At the last minute, Dubrowski, a widower in his upper 60s or low 70s, decided to join them as well. All of them were caught by Romania’s new Communist authorities and handed back to the Soviet Union. They were brutally interrogated, convicted of treason and sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment, the harshest punishment on the Soviet books at that time.23 Lepkivker would later recall his interrogator telling him they were lucky there was no official death sentence for they would have otherwise received it.24

The three younger convicts would have their sentences commuted during the post-Stalin amnesty, the charge of treason being re-adjusted to illegal border crossing. Junik, Lepkivker and Greenberg were all released in late 1953 or early 1954, and eventually allowed to leave the USSR.25 Dubrowski, on the other hand, was held for longer. The aforementioned Mulle Mochkin, who was arrested in 1951 as part of a separate case and spent time with Dubrowski in the Gulag, traveled to Siberia not long after his own 1958 release to visit his still-imprisoned friend. The shocking sight of Dubrowski’s physical deterioration left a life-long impression on him. Dubrowski was finally released sometime in 1959, but died shortly after returning to Chernovtsy.26

There is one more tragic detail. It was not, as the MGB document below asserts, four Chassidim caught crossing the border, but five. The fifth was Dubrowski’s 15-year-old grandson. Following the drowning death of Moshe Chaim’s son-in-law some years earlier, Dubrowski had taken in his two grandsons, Berel and Yehuda, and raised them as his own. Back in Lvov, Moshe Chaim had been particularly worried for the Jewish education and spiritual well-being of his teenage grandson Berel, and made sure to get him on a train out of the USSR.27 The younger grandson, however, remained with him. When Moshe Chaim chose to join the trek into Romania, he took Yehuda with him. At the time of their arrest, Yehuda was taken into custody and placed in a Soviet state orphanage.

It was decades before Berel Dubrowski managed to find his younger brother, by then known as Yura. Berel learned that his brother had gone on to serve in the Soviet army after which he settled in Chernovtsy. They exchanged letters over the years, but never saw each other again.28

The Crackdown

It was Abakumov who in October of 1946 first alerted Stalin to the threat posed to Communism by “Jewish bourgeois nationalism” and launched into the post-war antisemitic campaign against “Rootless Cosmopolitans,” i.e. the Jews.29 This dark period would see the liquidation of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee—the Jewish organization Stalin had established during the war to rally support to the Soviet cause and raise much-needed funds, whose members were arrested and shot after the war—and the lead up to the Doctors’ Plot, in which Jewish doctors were announced to have been part of a vast conspiracy to poison Soviet leadership, the development of which was only halted with Stalin’s sudden death in 1953.30 At this time of frenzy, it was only natural for the MGB to once again target the Lubavitcher Chassidim, a subversive group according to both Communist ideology and long-time Soviet policy.31 The case of the “Chassidim” was thus an important part of the investigation into the “Jewish bourgeois nationalists” being undertaken by the Ukrainian MGB, acting in accordance with the instructions it had received from the brigades of the MGB of the USSR in December of 1949, and order No.2 /3/1692 issued on Jan. 7, 1950, by the Second Main Directorate of the MGB of the USSR, the department charged with domestic counterespionage.

That this case was investigated as part of a broader attack on Jews helps explains the inclusion in the memo of Ben Zion Goldberg32 and doomed Yiddish poet Itsik Fefer,33 both of whom figure prominently in the case of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee.

The MGB had initially looked the other way as Lubavitcher Chassidim poured out of the Soviet Union in 1946, but things changed quickly. For one thing, by the end of the year there were so many obviously fake Polish Jews in Lvov that the MGB could no longer ignore it. The bigger factor, of course, was Stalin’s drastic shift on the Jewish question, with the years up to Stalin’s 1953 death remembered as the blackest for Soviet Jewry. Difficult times were in store for Jews in general and Chassidim in particular.

The Romanian endeavor appears to have been a trap set by the Soviet secret police. At one point during his months of interrogations, Yaakov Lepkivker’s interrogator demanded he stop lying. This office, the MGB investigator shouted, was “a temple of truth—khram istiny!” Interrogations nearly always took place at night, and the norm was for a prisoner to be led from his cell to the interrogation room and see no sign of life aside from his escorts. Once, due to some misunderstanding, Lepkivker was led out of his cell and contra protocol caught sight of a few people in the hallway. They’d quickly scurried away, but not before Lepkivker recognized one of the men. There, dressed in the uniform of an MGB officer, had been one of their “Romanian” guides.

“My father went into the room and yelled at the interrogator, ‘this is a temple of truth?!’ ” recalls his son, Rabbi Boruch Lepkivker. “Your officers are provocateurs and this was all a provocation!”

The final iteration of the Romanian escape plan might have been a trap, but the deputy minister of the MGB of Ukraine was not writing updates to Viktor Abakumov to keep him abreast of a mere local police affair. Senior Soviet security officials clearly believed that the Chassidim, led by Schneerson in New York, were a dissident group. While mixing in all sorts of nonsense, be it Polish imperialism in the 1930s or American intelligence in 1950, their case ultimately rested on the decades of leadership, organization and lobbying undertaken by the Sixth Rebbe, and his son-in-law and successor, the Rebbe, on behalf of the Jews of the USSR.

If Jews walking through fire to continue serving G‑d the way their ancestors had, through Torah study and mitzvah observance, was anti-Soviet, then Chabad-Lubavitch was indeed a threat to the regime. And in this sense, the Soviet security chiefs were absolutely right.

***

Note: We’ve tried to keep the translation of the MGB document as close to the original as possible. All handwritten notations in the document are rendered below in italics, with minor explanations included in brackets and larger ones in the footnotes. Biographical information for every known individual mentioned is included in the footnotes. A PDF of the original file, which comes from the Regional State Administration of the SBU, Kyiv, f.1, d.258, and has been made public by the Nadav Foundation, is appended at the bottom of this page.

******

Top-Secret34

June 6, 1950

N. 1487/n

To the Minister of State Security [MGB] of the USSR

Comrade Abakumov, V.S.,35

[Copy to] the Head of the 2nd Main Directorate of the MGB of the USSR, Major General Comrade Pitovranov, E.P.36

In 1949, information was received from foreign agents of the Ministry of State Security [MGB] of the Ukrainian SSR [Soviet Socialist Republic] that in the city of New York /USA/, under the cover of a school for the training of rabbis, an anti-Soviet center was created by American intelligence, which is headed by the famous Jewish tzaddik SCHNEERSON, who was expelled from the USSR in 1928.37

A European branch of this center was established in the city of Paris /France/ led by an American intelligence officer, GRIFFEL, Yakob [Yaakov], who is deputy chairman of the Zionist organization “Central Orthodox Committee.” /“KOK”/.38

According to the same information, the foreign Schneerson organization established contact with the anti-Soviet underground in the cities of Moscow and Chernovtsy and in December of 1948 organized an illegal escape from the USSR to Romania of four Chassidim /a religious sect/ Schneerson’s followers, who were detained as illegals by Romanian authorities and returned to the Soviet side.

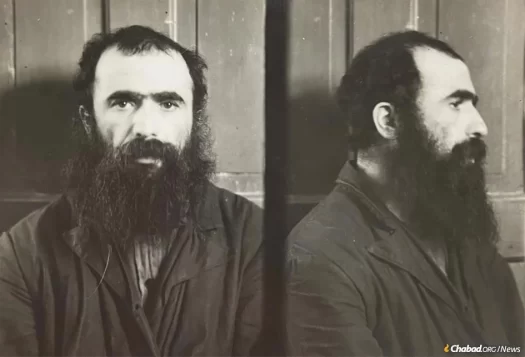

In reviewing this data, it was established that on December 9, 1948, the Romanian authorities did in fact hand over to the 31st detachment of troops of the Transcarpathian Border District the following defectors from the USSR, who were detained in the city of Radeutsy [Romania]: DUBROWSKI, Moshe-Chaim Evseevich – born in 1881; JUNIK-MARGULIS, Meir Tulovich – born in 193039 ; LEPKIVKER, Yakov Borisovich40 – born in 1930; and GREENBERG, Moses [Moshe] Naftulovich – born in 1930.41

During the investigation, these persons hid their membership in the illegal Schneerson organization and in March 1949 they were convicted as defectors by the Military Tribunal of the troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Carpathian Military District.

In order to verify the information received from the foreign agents, the convicts – DUBROWSKI, JUNIK, LEPKIVKER and GREENBERG were brought to the MGB of the Ukrainian SSR in the city of Kiev and underwent enhanced interrogation.

In the course of additional investigation by the MGB of the Ukrainian SSR, the enemy work of the Schneerson anti-Soviet organization illegally existing on the territory of the USSR, its connection with the Schneerson center in the USA and the branch in France, was partially revealed, and newly identified members of this underground were arrested.

Arrested in the case:

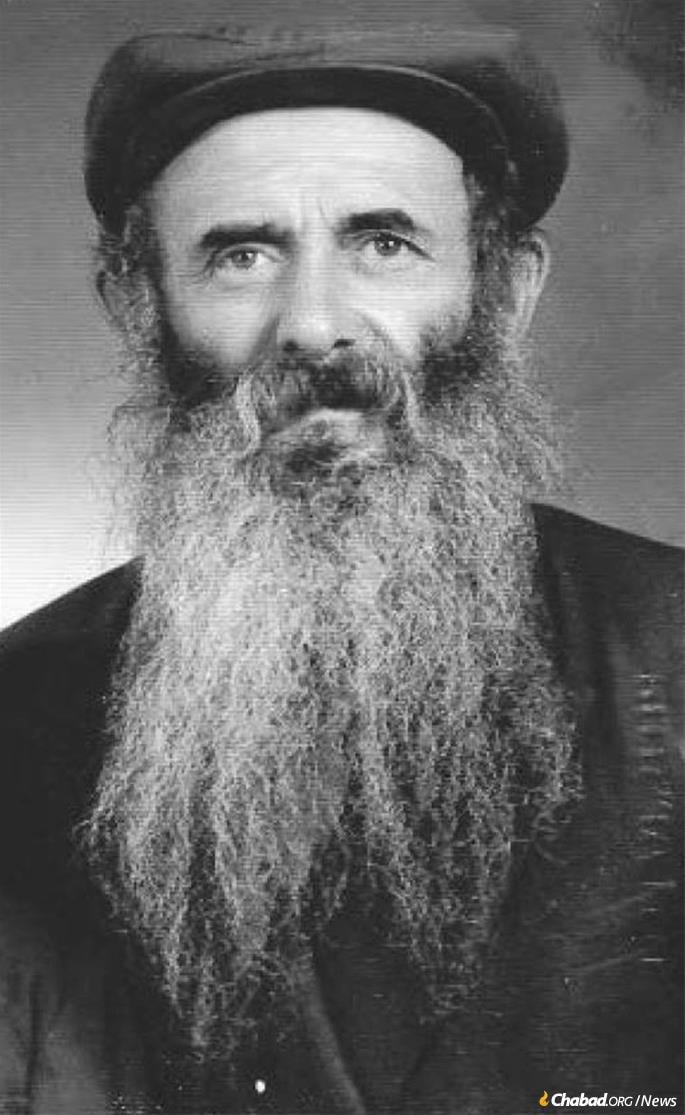

VISHEDSKY, also known as VITEBSKY Moses [Moshe] Pinchasovich – born in 1912 in Vitebsk, Jew, citizen of the USSR, without [political] party, prior to his arrest resident in Chernovtsy, worked as a foreman in a knitting factory.42

KOZLINER, Chaim Zalman Boruchovich – born in 1894 in Disna /Poland/, Jew, citizen of the USSR, without [political] party, no concrete occupation, resident of Chernovtsy.43

FLOM, Chaim Yechielovich – born in 1882 in the village of Secureni, Chernovtsy region; Jew; citizen of the USSR; with medium religious education; rabbi; resident in the city of Chernovtsy.44

Additionally, in April of this year in the city of Tashkent, at the orientation of the Ministry of State Security of the Ukrainian SSR, the Ministry of State Security of the Uzbek SSR discovered a Chassid-Schneersonite who had been evading arrest in the city of Chernovtsy:

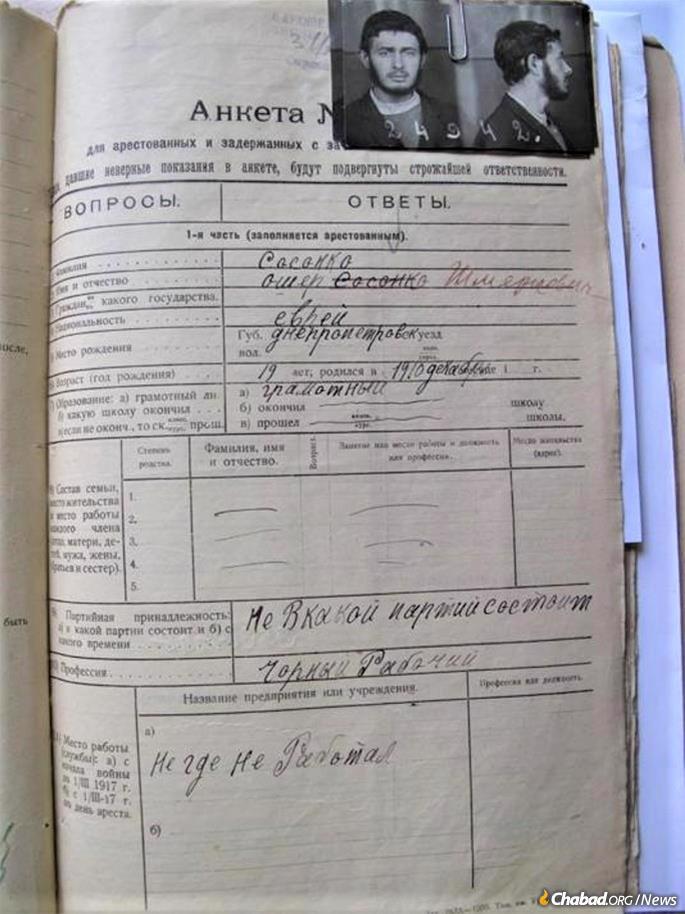

SOSSONKO, also known as BATUMSKI Asher Shmerkovich – born in 1889 in the city of Dnepropetrovsk, Jew, citizen of the USSR, without party, without concrete occupation or permanent place of residence.45

Materials regarding SOSSONKO-BATUMSKI have been sent to the Ministry of State Security of the Uzbek SSR for the purpose of his arrest and transfer to the MGB of the Ukrainian SSR – in the city of Kiev.

As established in the case, after Schneerson was expelled from the USSR, his followers, the Chassidim, continued to maintain illegal contact with him and did not cease their anti-Soviet activities.

During the period of the Great Patriotic War, the main mass of Chassidim evacuated to Central Asia, where, through Iran, they renewed their contact with SCHNEERSON in the USA.

According to SCHNEERSON’s directives, the Chassidim intensified their anti-Soviet activities and created illegal schools in the cities of Samarkand and Tashkent, in which Jewish youth who fell under their influence studied in a religious and nationalist spirit.

Those studying in the Schneersonite schools were provided with food, board and work in handicraft artels46 headed by Chassidim.

The arrested in the case, JUNIK-MARGULIS and GREENBERG, were students in these schools.

At the end of the war a directive was received from SCHNEERSON in the USA, through Chassidim associated with him – LEVITIN Samuel [Shmuel] – the son of the former rabbi of Kutaisi, who fled abroad to SCHNEERSON, and LEVITIN Samuel’s brother-in-law – BOBRUISKY, Eli [Gorodetsky, Binyamin], ordering the Chassidim of the USSR to flee abroad, for which it was recommended to utilize the Moscow-Lublin agreement on the repatriation of former Polish citizens from the USSR to Poland in force at that time.47

In the furtherance of this goal, the Chassidim – DUBROWSKI, Moshe; MOCHKIN, Leib / who has escaped over the border; FUTERFAS / arrested in 1947 by the MGB of Lvov as a defector; and others, in connection with the former chairman of the Jewish religious community [of Lvov] SEREBRYANI48 /convicted, did not testify/ organized an illegal crossing point in Lvov through which were ferried into Poland more than 100 Chassidim and Jewish nationalists,49 including those with connections to SCHNEERSON—LEVITIN, Shmuel and BOBRUISKY, Eli.

In their anti-Soviet work DUBROWSKI, MOCHKIN and FUTERFAS were connected with the Moscow-based representatives of the leadership of the Chassidic organization in Moscow- DUBIN, Mordechai; KAGAN, Yeina50 ; GURARI, Mottel; and LEVERTOV, Berel51 / who were at various times arrested and convicted by the MGB of the USSR/, [and] at whose direct instructions [Dubrowski, Mochkin and Futerfas] carried out their work.

During the period of the Great Patriotic War DUBIN, Mordechai lived in the city of Kuibyshev, [Russia], where he maintained suspected espionage connections with representatives of the Polish, English and American embassies.

As has been established, SOSSONKO-BATUMSKI and DUBROWSKI were connected with the Chassidim KANTROVICH, ZHIVOTOVSKY, SHILENSKY, MINTZ and others in the city of Lvov, as handled by the agent in the case of the “CHASSIDIM,” influencing them and slanting them towards the activation of anti-Soviet activities.

According to intelligence data, these persons organized gatherings in the apartment of SHILENSKY and other Chassidim, engaged in illegal crossings of Jews over the border, and also organized an illegal Schneerson school, the funds for which were received through the Jewish religious community.

According to the same information the Chassid – SHILENSKY, Boris Nachmanovich – born in 1896, doctor by profession, received higher education in Germany, fluent in English, French and German, lived in Moscow until the beginning of the war where he worked as a translator in the “Intourist” hotel, was acquainted with the former U.S. ambassador to the USSR HARRIMAN, with whom he allegedly met in person in the synagogue.52

SHILENSKY currently resides in the city of Vilnius, and the MGB of the Lithuanian SSR is preparing to arrest him.

In addition, the MGB of the Ukrainian SSR has intelligence information that Lvov resident MINTZ /no other information/ met with the American spy WAIFE-GOLDBERG, [Benjamin/Ben Zion], who visited Lvov in 1946 under the guise of journalism, and told MINTZ that in the USA lives the famous rabbi of LUBAVITCH/SCHNEERSON – born in the village of Lyubavichi/ who gave the orders for the relocation of Chassidim from the USSR to the other side of the border.53

According to information provided by the source “YUREVOI” and the testimony of the arrested FEFER, Isaac [Itzik], who is in the custody of the MGB of the USSR, in 1946 MINTZ, at the direction of WAIFE-GOLDBERG, traveled to the Drogobych region to search for the daughter of the former rabbi of Lvov FEINER-GUTKO, who lives in the USA, in order to transfer her abroad.

It has been established that the thirteen-year-old daughter of FEINER-GUTKO was really brought up by citizen PETRIKEVICH, Darya Nikolaevna, who lives in the Truskovets settlement, Drogobych region, and was taken from there in 1946 by an unknown foreigner.

Whether this MINTZ is the same person as the one handled by the agent in the “CHASSID” case has not yet been established. There are several individuals in Lvov with the family name MINTZ, and it is still under investigation.

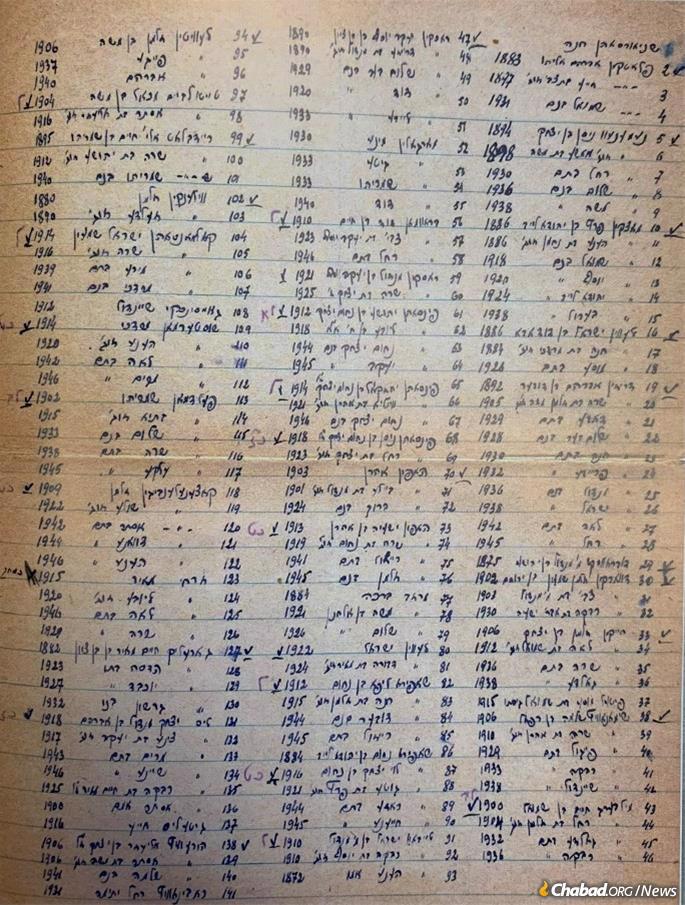

Pursuant to the undercover “CHASSIDS” case of the Ukrainian MGB of the Lvov region, 12 people are currently being investigated.54

Investigative measures by our agents also established that after the arrest in 1947 in the city of Lvov of a number of participants in the illegal crossings [including] / FUTERFAS, SEREBRYANI, [and] KOZLINER / the Chassid DUBROWSKI hid in Minsk, where he tried to resume the illegal crossing of SCHNEERSON’s followers, but was allegedly unsuccessful, while SOSSONKO-BATUMSKI fled to Chernovtsi, where he established an illegal connection with Zionists living in Bucharest.

As has been established, the crossing of the state border by the convicted JUNIK, LEPKIVKER and GREENBERG in December of 1948 was organized by the French branch of the Schneersonite center through the chairman of the Bucharest Zionist organization “AGUDAT”55 – PORTUGAL, SUZI [Zusia]56 ; emissary of the Zionist center “KOK” in Paris SHUB, Zalman [Abelsky, Zalman],57 and the Chassidim SOSSONKO-BATUMSKI, FLOM and VISHEDSKY.

PORTUGAL, [Zusia] – rabbi, former deputy chairman of the Jewish religious community in Chernovtsy, from which he ran to Bucharest in 1946 where, aside from the Zionist organization “AGUDAT,” he directs Jewish childrens’ orphanages.

SHUB, Zalman, who is suspected of belonging to American intelligence, arrived in Romania illegally from France in the interests of bringing the children of the Jewish orphanages to Palestine. He hid in PORTUGAL’s apartment for two months.58

Having established contact with the Zionist underground in the USSR and in an attempt to resume their escape over the border, SHUB, Zalman and PORTUGAL [Zusia] sent two couriers to Rabbi FLOM with a letter for SOSSONKO-BATUMSKI containing SCHNEERSON’s instructions that Chassidim escape over the border, and it was proposed to use the services of the letter-couriers for this purpose. This was attempted by the Chassidim in Chernovtsy, albeit unsuccessfully.

Having received a message from members of the “AGUDAT” organization BOYMAN, Naftul, who lives in the city of Radeutsy,59 and WAGNER, Michel, who lives in Gura-Gomurului,60 regarding the detention by the Romanian police of a group of Hasidim who had fled from the USSR, SHUB, Zalman, together with the senior administrator of orphanages SALTEPER, immediately left for Radeutsy, with the intention of offering a large bribe to release the detainees, but they were too late, since the detained Chassidim had already been handed over by the Romanian police to the Soviet border guards.

Likewise preparing to cross the border was the arrested Chassid-Schneersonite KOZLINER Chaim-Zalman Borukhovich who, while living in Lvov back in 1946-47, was also associated with the Chassidim and their illegal border crossings.

His wife KOZLINER, Tzipa, was arrested in 1947 as a participant in the illegal border crossings and sentenced to 10 years in Corrective Labor Camps. In 1949, however, she was released from custody under unclear circumstances, and [after that] lived with her husband in Chernovtsy. Having learned about the arrest of DUBROWSKI, she went into an illegal hiding.61

During the investigation Rabbi FLOM, who was arrested in the case, confirmed his relationship with PORTUGAL, [Zusia], which, according to his statement, was carried out through his daughter SHLINGER, Chaya, who lived in Bucharest at 37 Poparadu Street.

FLOM likewise testified that in 1949, after the collapse of the illegal crossing of the Chassidim into Romania, PORTUGAL was arrested by Romanian organs but after two months under custody was released.

This information became known to him shortly before his arrest, allegedly from his daughter’s letters, [which is] of a specific nature.62

The case of FLOM continues to be thoroughly investigated.

Upon the transfer of SOSSONKO-BATUMSKI from the MGB of the Uzbek SSR to the MGB of the Ukrainian SSR, the latter will be taken for enhanced interrogation.

I will report on the results.

Attached are the protocols of interrogation of Junik [and] Lepkivker on 22 sheets, copies only for the 2nd Main Directorate of the Ministry of State Security of the USSR.

DEPUTY MINISTER OF STATE SECURITY OF THE Ukrainian SSR

Major General Popereka

Below is a copy of the memo to secret police chief, Viktor Abakumov dated June 6, 1950.

FOOTNOTES

1. Vadim J. Birstein, SMERSH: Stalin’s Secret Weapon (Biteback Publishing, London, 2011) pp. 193-206, 404.

2. On Jan. 14, 1947, William Bein, director of the post-war American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (AJDC) in Warsaw, wrote to the JDC’s Dr. Joseph J. Schwartz in New York: “This is to follow up my letter #4 concerning the Lubavitcher. … Summarising [sic] all the persons arrived up to-day we come to a total of 1,223 souls.” At the time, Bein was expecting the imminent arrival of another group of 386 assembled in Lvov, but by that time the Soviet secret police had closed in and begun arresting Chabad activists. There would be no more escapes via Lvov from that point on. JDC Archives, Records of the New York Office of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, 1945-1954, Folder: Lubavitch Yeshivah, 1945-1954, Letter from Melvin S. Goldstein to Dr. Joseph J. Schwartz. A January 1947 report sent from Poland to the Sixth Rebbe in New York and signed by organizers Yitzchak Goldin, Bentzion Shemtov, Schneur Zalman Butman and Leibel Mochkin states that “more than 1,000 souls” had arrived safely in Poland, all of whom are thankful for their deliverance and share “the hope we can see the Rebbe soon.” See Sholom Dovber Levine, Toldos Chabad Be-Rusia HaSovetis, (Kehot Publication Society, Brooklyn, 1989) p. 397.

3. For more extensive descriptions of the Great Escape, see Sholom Dovber Friedland, Peilot Chutzah Gevulot Vol. 1 (Paris, 2017), a fantastic resource based on the extensive archives of Sholom Mendel Kalmenson, a key coordinator of the escape effort; Levine, pp. 390-398; Irina Osipova, Hasidim: Save Thy People (Russian-language, Moscow, 2002), pp.125-153; and Dovid Eliezrie, The Secret of Chabad (Toby Press, 2015), pp. 73-88. See also Moshe Levertov’s chapter on the escape in his memoir The Man Who Mocked the KGB, available here.

4. Zvi Gitelman, Jewish Nationality and Soviet Politics (Princeton, 1972), p. 307, fn. 204.

5. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson was arrested in 1939 and passed away in 1944 as a direct result of his treatment in Soviet custody. Stalin ended the Great Terror in the end of 1938, and after that point, especially in the immediate aftermath, harsh exiles and terms of imprisonment were more common. Lubavitcher activists arrested during the Great Terror of 1937-38, such as the Sixth Rebbe’s secretary Chonye (Elchonon Dov) Morozov, were for the most part shot.

6. The boy, whose last name was Kogan, was the nephew of Lazar Kaganovich’s older brother Aaron M. Kaganovich. Aharon Chazan, one of the underground yeshiva network’s administrators, recalls that Kogan’s father was a Communist Party member purged in 1938 and that the yeshivah was initially afraid of accepting the boy due to his family connections. They took him anyway and Kogan excelled in his studies. He ultimately decided to have himself circumcised. “Seeing him in such pain during the operation [this being before readily-available anesthetic], his mother started to cry. He shook his hand at her, though, and said, ‘Whose fault is it that I have to go through this now?’” Aaron Chazan, Deep in the Russian Night (CIS Publishers, 1990), p. 126.

7. Albert Kaganovitch, “Stalin’s Great Power Politics, the Return of Jewish Refugees to Poland, and Continued Migration to Palestine, 1944–1946,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 26, no. 1 (Spring 2012): 59–94.

8. Gennady Estraikh, “Escape through Poland: Soviet Jewish Emigration in the 1950s,” Jewish History 31, 291–317 (2018).

9. Friedland, Peilot Chutzah Gvulot, Vol. 1, p. 53.

10. Forthcoming memoir of Leibel Mochkin.

11. The Lvov court of 23 (Beis Din Chof Gimmel) modeled the “lesser Sanhedrin” of 23. Since the question of whether to attempt leaving the Soviet Union and if so, how to do it, was deemed a matter of life-or-death, the Chassidim chose 23 judges—the minimum number required by Jewish law to adjudicate capital cases. See here for more on the Sanhedrin.

12. Moishe Levertov recalled that not all of the court’s members were ordained rabbis, “but all were Torah scholars and respected Chassidim.” The rabbis included Rabbi Nochum Shmaryahu Sossonkin, Rabbi Shneur Gorelik, Rabbi Shmuel Notik and Rabbi Avraham Glazman. The respected Chassidim included Mendel Futerfas, Abba Levin, Moshe Chaim Dubrowski, Shlomo Chaim Kesselman and Yona Kahan.

13. Interview with Berel Dubrowski, Aug. 19, 2022.

14. Osipova, pp. 136-42.

15. In a talk on her yahrtzeitin 1981, the Rebbe pointed out that while low-level Soviet officials might have been fooled, the top echelons were well aware of the escape.

16. Friedland, Peilot Chutzah Gvulot Vol. 1, p. 118.

17. Ephraim Dekel, B’riha: Flight to the Homeland (Herzl Press, New York, 1972), pp. 194-97.

18. The group including Mendel Futerfas and Shmuel Notik was on a train and just over the border in Medyka, Poland, when they were stopped and arrested on Jan. 24, 1947. Osipova pp. 268-69. Futerfas was released from the Gulag in 1956 and made it out of the USSR in 1964. The Rebbe later appointed him as the Chassidic mentor in the Lubavitcher yeshivah in Kfar Chabad, Israel. Notik, who died in the Gulag in 1949, is warmly recalled in the memoirs of dozens of his students. His surviving family would later emigrate from the USSR.

19. Chernovtsy is the Russian spelling of what is today Chernivtsi, Ukraine. It was called Cernăuți when it was part of Romania and Czernowitz in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

20. Mordechai Altshuler, “The Soviet ‘Transfer’ of Jews from Chernovtsy Province to Romania, 1945-1946,” Jews in Eastern Europe 2 (33) (1998), pp. 54– 75.

21. It was written in “mezuzah code.”

22. Friedland, Peilot Chutzah Gvulot Vol. 1, pp. 275-295.

23. Between May 1947 and May 1950 a term of 25 years formally replaced the death sentence as the harshest Soviet punishment. Soviet security organs nevertheless had ways of executing people, including specially-administered poisonous injections. Former KGB spymaster Pavel Sudoplatov describes in detail Lab X located in the Lubyanka (secret police headquarters in Moscow) and believes this was how Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg was murdered in July 1947. See Pavel Sudoplatov, Special Tasks (Little, Brown and Company, 1994) pp. 269-71. The Yiddish actor Solomon Mikhoels was likewise killed with a poisonous injection in January 1948 before his body was thrown under the wheels of a truck to make it look like an accident, Sudoplatov, p. 297.

24. Interview with Yaakov Lepkivker’s son Rabbi Boruch Lepkivker, Aug. 18, 2022. Asher Sossonko, who was also involved with the escape attempt and whose arrest is described below by the MGB, was sentenced to 10 years in the Gulags. He likewise remembered his interrogator telling him he was fortunate the death sentence had been suspended. Naftali Gottleib, Yahadut Ha’Dmamah Vol. 2 (Jerusalem, 1987), p. 148.

25. Greenberg was granted permission to leave the Soviet Union in 1966, Lepkivker in 1969 and Junik in 1971.

26. His yahrtzeit is the 21 of Av, apparently 5719/1959. Interview with Berel Dubrowski, Aug. 19, 2022.

27. Berel Dubrowski escaped on the transport that left Lvov on 19 Kislev, 5707 (Dec. 12, 1946), anniversary of the liberation of the founder of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, from Czarist imprisonment. Dubrowski remembers the Chassidim in Lvov, his grandfather included, having a spirited farbrengen to mark the occasion the night before he left.

28. Interview with Berel Dubrowski, Aug. 19, 2022.

29. Sudoplatov, p. 294. It was also under Abakumov’s watch that the case against the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was formed and Doctors’ Plot planned. Nevertheless Abakumov soon fell out of favor and was arrested on July 12, 1951, being accused of, among other things, not pursuing the Doctors’ Plot strongly enough. Abakumov was executed in 1954 in the power struggle that erupted after Stalin’s death.

30. For more on the destruction of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee see Joshua Rubenstein and Vladimir Naumov, Stalin’ Secret Pogrom, (Yale, 2001). For a detailed look at the Doctors’ Plot see Jonathan Brent and Vladimir P. Naumov, Stalin’s Last Crime (HarperCollins, 2003).

31. Chassidim were regularly charged with Article 58-10 of the Russian Criminal Code—anti-Soviet and counter-revolutionary activity—and the much more severe Article 58-11, which denoted membership in an anti-Soviet and counter-revolutionary organization. Just being a Chassid meant you were part of an illegal and necessarily anti-Soviet organization. In the slew of arrests of Chassidim in March 1939 in Kiev, each of the 10 Chassidim arrested were charged with having a photo of the Sixth Rebbe in their possession, among other charges.

32. Ben Zion Goldberg (born Benjamin Waife, 1895-1972) was the son-in-law of the Yiddish writer Sholom Aleichem. A man of the left, he’d for decades been a Soviet fellow traveler and headed the organization that had sponsored the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee’s successful war-time visit to the United States. Goldberg visited the USSR a number of times, most recently as a journalist in 1946, but with Stalin’s post-war shift against the Jews, Goldberg, safely in the United States, was accused of being an American spy, and all Russians who’d met or worked with him became suspect.

33. Itsik Fefer (1900-1952), was a Soviet Yiddish poet who’d been vice chairman of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee before its liquidation and his subsequent arrest. He was executed in 1952 on what is commonly called the “Night of the Murdered Poets.”

34. The memo is written by KGB Maj. Gen. Mikhail Stepanovich Popereka (1910-1982), an ethnic Ukrainian who was deputy minister of state security of Ukraine from 1946-1952.

35. Viktor Semyonovich Abakumov (1908-1954), head of the MGB at the time. See fn. 1 and 29.

36. Evgeny Petrovich Pitovranov (1915-1999), at various times minister of state security of Uzbekistan, deputy minister of the MGB of the USSR, and head of counterintelligence. A key figure in the post-war attack on Jews, Pitovranov was arrested in October of 1951 as part of the case against his former boss Abakumov, but released by Stalin a year later and placed back at his position in the MGB.

37. Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak left the Soviet Union in October of 1927. In general, Popereka’s memo is sloppy, often missing words and making simple grammatical and factual mistakes. Abakumov, on the other hand, “was very literate, often editing documents written by his barely literate subordinates.” Birstein p. 194..

38. Dr. Yaakov (Jacob) Griffel (1900-1962) was an Orthodox Jewish activist who at various times represented the Vaad Hatzalah, Agudas Yisrael and the Central Orthodox Committee in Europe. Contra the MGB’s assertion, none of these organizations were formally Zionist. Griffel was stationed in Istanbul during World War II where he played an important part in the successful negotiations that led to 1,200 Jews being released from the Nazi Theresienstadt camp to Switzerland. After the war he was based throughout Europe, including in Paris and Prague. Griffel did work together with Lubavitch during and after the war and there is a lengthy correspondence between him and the Sixth Rebbe, and it is possible the extent of his cooperation is still unknown. For example, in a late 1946 response to a letter mentioning Griffel from Yisrael Jacobson, Sholom Mendel Kalmenson wrote: “Regards from R’ Yaakov Griffel, he is interested in our affairs and assists with advice and concrete action.” See Friedland p. 72. Nevertheless, he was by no means the leader of Chabad’s activities in Europe.

39. Meir Yechezkel Junik (1929-2009) later lived in Montreal and Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Junik was arrested in Lvov in late 1946 on a minor police matter, but by the time he was released had missed the chance to leave the Soviet Union that the rest of his family had taken. Following his release from the Gulag in connection with the Romania affair, he married the daughter of Shmuel (Krislaver) Notik, see above. With the blessing of the Rebbe, he and his family were allowed to emigrate in 1971.

40. Yaakov Yosef Lepkivker (1928-2015) later lived in Bnei Brak, Israel. For years, Lepkivker’s brother-in-law Yaakov Lipskar would mention his name and his family’s to the Rebbe with the request for a blessing that the Lepkivkers be allowed to emigrate from the Soviet Union. In 1969 Lipskar entered the Rebbe’s office for a private audience and before he had the chance to say anything the Rebbe said “G‑d willing this year you will be with your brother-in-law.” The Lepkivkers were in Vienna by Passover of 1969.

41. Moshe Greenberg (1927-2013), later lived in Bnei Brak, Israel. Following his conviction and sentencing to 25 years in the Gulag, Greenberg made the decision to never violate Shabbat, eat non-kosher meat or eat chametz on Passover. He did this despite it not being required by Jewish law because he made the calculation that he could never survive 25 years in the Gulags, and therefore if he was going to die anyway, he might as well continue living as a religious Jew for as long as he could make it.

42. Moshe Vishedsky (1912-1986), known as Moshe Vitebsker (Vitebsky in the MGB’s rendition) had been the original initiator of the Romania escape plan, and the five Chassidim spent their last Shabbat in the USSR in the Vishedsky home, where they were cared for by Moshe’s wife, Chasya. A short time after the group left Moshe came to the synagogue in Chernovtsy and saw two MGB agents holding Moshe Greenberg near the entrance—Vishedsky understood what that meant right away. Friedland p. 292. Vishedsky was released in 1955 and emigrated from the Soviet Union with his family in 1965. For more see interview with his son Benzion Vishedsky here.

43. Chaim Zalman Kozliner (1901-1985) served as a secretary for the Sixth Rebbe for a period in the 1920s. Was first arrested in the early 1930s and spent a few years in the Gulag. He was very active in the escape from Lvov before his 1948 arrest in Chernovtsy, which took place only a few months after his wife Tzipa’s release (see fn. 57). Following his release in late 1953 he and his family lived in Chernovtsy, then Samarkand, before finally arriving in Israel in the early 1970s.

44. I have yet to find any information regarding Chaim Flom. It’s very possible Flom is not his real name.

45. Asher (Sossonkin) Sossonko (1911-1988) was the only surviving son of Nachum Shmaryahu Sossonkin, his two brothers Moshe and Chaim having been arrested in Leningrad in 1938 and dying in the labor camps. Asher Sossonko (known as “Batumer,” rendered by the MGB as “Batumski,” for the Georgian city of Batumi where he grew up after his father was sent there as an emissary by the Sixth Rebbe) was imprisoned three times all together, this being his second and longest imprisonment, lasting six years. He emigrated to Israel with his family in 1964.

46. Cooperative association.

47. Communication between the Sixth Rebbe in New York and Chassidim in the Soviet Union was understandably extremely difficult during this period, and as can be gleaned from this memo alone, just associating with the name Schneersohn was dangerous. Despite all communications in the Soviet Union going through a censor, Chassidim did not cease sending their questions to the Rebbe, nor did he stop responding or writing to them. It appears that Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s first response to the question of whether to leave the Soviet Union via Lvov was dated Dec. 12, 1945 (8 Tevet, 5706) and was communicated from Rabbi Shmuel Levitin (1883-1974) in New York to his son-in-law Binyamin Gorodetsky. At this time the Sixth Rebbe’s response was to remain in place. Some months later clear indications from the Sixth Rebbe arrived that the Chassidim should go ahead with the escape plans, see Friedland pp. 53-54. It appears that the MGB may have confused things in this memo: The initial communication was indeed sent by Shmuel Levitin, but he was not the son of the former rabbi of Kutaisi, Georgia, but the rabbi himself (Levitin had been sent as a Chabad emissary to Georgia by the Fifth Rebbe, Rabbi Sholom Dovber). In the mid-1920s Levitin headed the yeshivah in Nevel and was arrested when it was closed by authorities in late 1928, serving about two years in the Gulags. He left the Soviet Union in 1937 and was in the United States when World War II began. Alternatively, the MGB may be referring to Shmuel Levitin’s son Avraham Yaakov Levitin, who left the Soviet Union via Lvov in 1946. The man the MGB calls Eli Bobruisky is Shmuel Levitin’s son-in-law Binyamin Gorodetsky, whose middle name was Eliyahu and who came from Bobruisk. Gorodetsky (1907-1995) was subsequently appointed the Sixth Rebbe’s representative to Europe, a position maintained by the Rebbe, where he served as a major Chabad activist. With the financial support of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Gorodetsky also energetically oversaw Chabad’s pioneering work throughout North Africa.

48. Lev Serebryani (originally Silver) the head of the Jewish community of Lvov, served five years in the Gulags before being released in 1953.

49. The MGB notes elsewhere that the Chassidim’s illegal crossing point in Lvov helped 100 families leave the USSR.

50. Yonah Kahan (“Poltaver”).

51. According to Chaim Zalman Kozliner, who was with Berel Levertov during his last moments, Levertov passed away on 7 Elul 5709 (Sept. 1, 1949) in the Gulag.

52. Not much is known about Dr. Boris (Boruch) Shilensky. According to Emmanuel Mikhlin, Shilensky was born in an anti-religious Jewish home but had a thirst for Judaism, becoming an active member in Moscow’s Tiferes Bachurim yeshivah for young working men. Hagachelet, (Shamir, 1986), p. 43.

53. Whether the accusation that the Sixth Rebbe had sent a message with him has any truth is impossible to know.

54. Indeed, more arrests would follow, including that of “Mumme [Aunt]” Sarah Katzenelenbogen, who was arrested in 1951 and died in custody a year later. Sarah Rapoport was arrested in 1950, within months of this memo, and nearly simultaneously as her husband, Michel. The Rapoports served nearly a decade in the Gulag before both being released around 1959. During that time their toddler-age son lived with Sarah Rapoport’s father.

55. Agudas Yisrael.

56. The Skulener Rebbe, Rabbi Eliezer Zusia Portugal (1898-1982). Served as rabbi of Sculeni, today Moldova, and then Chernovtsy when they were both part of Romania. Went to Bucharest after the war where he established orphanages to care for hundreds of Jewish war orphans. Was arrested, together with his son (and later successor) Rabbi Yisroel Avraham Portugal by Romania’s Communist government in 1959, and released as a result of an international campaign. Arriving in the United States, he settled in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. For more on the Rebbe’s role in the rescue of the Skulener Rebbe and his son see Dovid Zaklikowski, “A Portrait of Piety and Heroism: How the Skulener Rebbe, zt”l saved thousands of Romania’s Jews,” Ami Magazine, Aug. 8, 2018.

57. Zalman Shub is the previously mentioned Zalman Abelsky, whose mother’s maiden name was Shub. While he was not sent to Romania by the Central Orthodox Council, he was in touch with Yaakov Griffel throughout his mission, see Friedland, pp. 285, 289. Griffel also visited Romania in 1948 while working to help evacuate the Jewish orphans out of Romania, and they were in touch then. For more on Griffel’s work in Romania see JDC Archives, Records of the New York Office of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, 1945-1954, Folder: Jewish Central Orthodox Committee, 1948, Letter from Abraham Horowitz to Henrietta K. Buchman, and Folder: Orthodox Children, III-VII, 1949, Memorandum, March 2, 1949.

58. Abelsky (Shub) did spend significant time with Portugal during his stay in Bucharest, working for a time in Portugal’s orphanages.

59. Rădăuți, Romania

60. Gura Humorului, Romania

61. Tzipa Kozliner (d. 1999) was in fact arrested in Nov. 1946. She was caught walking out of the OVIR office with a substantial sum of money, a list of names and accompanying documents to which to have exit visas affixed to, and pushed into a car by two MGB agents. Her release was gained with the aid of her sister, Musia Katzenelenbogen, who traveled to the labor camp where Kozliner was serving and met with a member of the camp administration. The administrator told Musia that commutation was available for lesser criminals but not someone like Tzipa who’d been sentenced to 10 years for treason and cross-border smuggling. Shortly thereafter Tzipa was admitted to the camp hospital for an underlying heart condition. At the same time, a camp inmate murdered another inmate and an investigative committee arrived on the scene. Utilizing this confluence of circumstances, Musia managed to contact the camp doctor and convinced him to recommend Tzipa’s early release due to her “drastic” illness, a recommendation the visiting investigators immediately approved. Kozliner was released on Aug. 14, 1948. See Halperin teshura, 6 Tammuz 5768.

62. It’s not clear to me what this means. It appears to be coded language or some kind of MGB internal reference.

Mummeh Sarah

Where does she come into the picture?