Hundreds Gain Rabbinic Ordination While Deep Into Successful Careers

by Menachem Posner – chabad.org

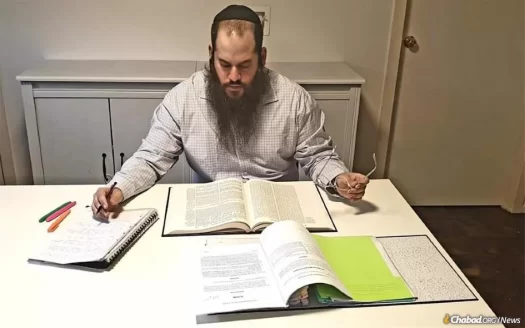

Zach Gomo is far from uneducated. Yet even with two advanced degrees, the assistant principal of Bialik College—an acclaimed Jewish day school in Melbourne, Australia—still wanted more. And at the age of 34, studying mostly alone at home, he has now become a rabbi as well, a crowning achievement for someone who embraced religious observance as a teen.

Gomo is among a growing crop of students drawn from a broad variety of professions who are challenging themselves to achieve rabbinic accreditation, even though they have no intention of actually ascending the pulpit.

For much of Jewish history, becoming a rabbi was something most could scarcely dream of. Working men were fortunate if they could sit in on a class on the weekly Torah portion or Talmudic homilies.

While large, organized yeshivahs in Europe, Israel and then in North America made in-depth Torah study more accessible since the 19th century, rabbinic ordination was often seen as a bonus, to be pursued by only a small cadre of advanced students.

However, the Rebbe—Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory—wanted it to be something every young (and not so young) man could attain.

Speaking at a gathering in January of 1952—less than a year after he formally accepted the leadership of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement—the Rebbe called for both married and unmarried men to study the syllabus of Jewish law learned by rabbinical candidates.

Addressing the family men, the Rebbe said: “The slip of paper and the signature don’t matter so much. The main thing is that you’ve learned to the point that you’d be able to be awarded the certificate.”

To the full-time students, however, the Rebbe was more demanding. “When you receive the certificate, you’ll know that you’ve learned what you need to have learned,” he said. “In fact, it would be ideal that the tester should be strict, so that it will be clear that everyone learned the laws properly.”1

The following year, in a letter to Rabbi Nissan Nemenow—the dean and mentor of the Chabad yeshiva in Brunoy, France—the Rebbe clarified that the semichah students should continue to advance in Talmud, focusing on topics with practical day-to-day application alongside their studies in Jewish law.2

Responding to the Rebbe’s Call

Heeding the Rebbe’s call, the leaders of the Chabad-run Rabbinical College of Canada in Montreal added an organized track for ordination. In 1955, they celebrated the first cohort of 10 rabbis, some of whom were native-born, while others were survivors of the Holocaust or of Stalin’s oppression.

In addition to the city’s chief rabbi, Shea Herschorn, who tested the students and conferred ordination, Member of Parliament Leon Crestohl was in attendance, as well as hundreds of well-wishers. The Rebbe sent Rabbi Solomon S. Hecht of Chicago as his personal representative at the event.

In addition, the Rebbe sent a Yiddish letter of greeting in which he explained, “Even if in previous years the primary focus of the yeshivah was to cultivate students with deep knowledge of Torah, not worrying about influencing those around them, today the primary mandate of a yeshivah is to raise not only scholars who are G‑d fearing, well-mannered, and Torah observant, but those who feel responsibility toward others … ”

In his letters to students over the decades, the Rebbe made it clear that he saw learning towards rabbinic ordination not just a path to the pulpit, but as a motivator and way of self-guiding the student.

In addition to ensuring that there was a steady stream of available young rabbis, ready to serve in communities all over the world, mainstreaming ordination meant that the homes of the rabbis—even those who never practiced as such—were conducted in accordance with Torah.

This goal, of course, is equally important to professionals or others with established careers. Thus, over the years, many Chabad communities have created semichah programs catering to their members.

At a Chicago event in December of 2012, in which former Israeli Chief Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau conferred semichah on 14 members of the community, ophthalmologist Dr. David Spindel explained, “It has always been my lifelong dream to become a rabbi, to go for semichah, even though I’m not quitting my day job yet.”

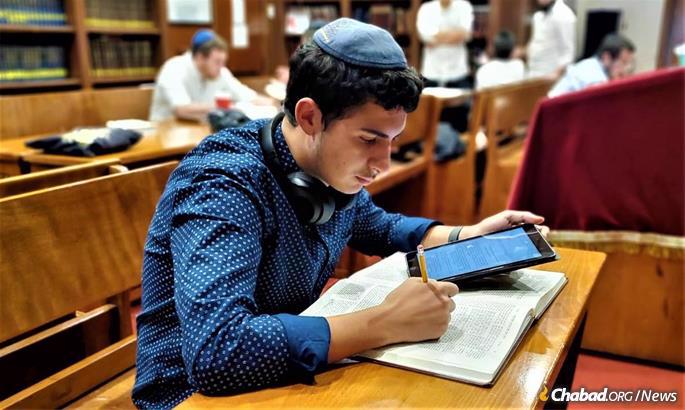

Like much of academia, the path towards semichah has also moved towards online in recent years.

Just a few months before the Chicago event, an organization known as Online Smicha graduated its first class of 17 rabbis in the spring of 2012.

Technology Brings Study to Isolated Rabbinic Hopefuls

Under the tutelage of Minnesota-based Rabbi Nachman Wilhelm, they had learned via then-new technology: online classrooms, real-time video-streaming and screen-sharing.

The world of online ordination took a massive step forward during coronavirus lockdowns, when many people were at home looking for meaningful activities to fill their days.

“We had been a small program serving mostly young men who had begun learning in yeshivah but had left for one reason or another and still wanted to continue learning,” says Rabbi Shlomo Chaim Kesselman, director of Machon Smicha. “Then, right around Pesach of 2020, things exploded, and we had an influx of older students.”

Gomo says his country’s extensive Covid lockdowns were what finally pushed him towards semichah.

He had spent a few years in yeshivah before attending college, but semichah always seemed out of reach.

Then, stuck at home all day with few distractions, he began learning for semichah.

In addition to the staff provided by the program, he leaned into local rabbis who discussed his studies with him and provided guidance whenever needed.

Kesselman now enrolls 150 students and employs a team of course writers, mentors and teachers. He takes pride in his syllabus, which is exhaustive in scope. Yet everything is translated into English, ensuring that even those who never had the opportunity to learn to understand Hebrew are able to participate.

Students at Machon Smicha are tested by Rabbi Chaim Finkelstein, South African-born protégé of the late Rabbi Zalman Nechemia Goldberg.

According to Kesselman, the new enrollees include a Yale-educated law professor, a university vice president and others. “These are lifelong learners, very smart, very well-educated, who are looking for something new to learn and a way to advance as Jews,” he says. “Some choose to do everything pretty much on their own, while others are in contact with faculty several times a day. It’s really up to them.”

Kesselman says he makes it clear to candidates that online learning has its limits and that even after graduating, they may not issue guidance in Jewish law or lead a congregation unless they have apprenticed under an established Orthodox rabbi and gained hands-on experience.

International Program in Five Languages

On the international scene, the Lemaan Yilmedu organization organizes semichah courses in Hebrew, French, Spanish and Russian—and, of course, in English.

The English program was founded by the acclaimed educator and scholar, Rabbi Zushe Wilhelm, who passed away earlier this year at the age of 62.

“Rabbi Wilhelm was a first-class scholar,” says administrator Shraga Crombie. “He knew so much and had so much knowledge. Yet he spent hours preparing each class, working to find the best and clearest way to present each idea, guiding the students through each subject.”

Even after Wilhelm’s passing, his classes on the entire syllabus were fully recorded and are available for students currently enrolled in the program, alongside live classes from other lecturers.

“We do not cut corners or take shortcuts,” says Crombie. “Even though they come from varied backgrounds and have limited time, the students in our program are learning on the same level as those in yeshivah, and the rabbis who tested them are blown away by the depth and breadth of their knowledge.”

This article has been reposted with permission from chabad.org