Aleph Rescues Afghans from Taliban

by Yoni Brown – Lubavitch.com

When the Taliban started sending him death threats, Fazel Malek* had to leave his wife and daughter behind in Kabul, Afghanistan. After a team of Chabad rabbis arranged his family’s rescue, he’s now living at a Chabad Jewish Center in Fremont, California, and eagerly awaiting his family’s arrival.

In the closing days of August 2021, Shirin Malek* and her young daughter pushed their way towards the Kabul airport. In her hands, she clutched the documents that identified them as employees of the United States. Malek’s husband Fazel had spent years working for the United States embassy, making the entire family a Taliban target, and qualifying them for visas to the United States.

Thousands of desperate Afghanis and foreigners crowded the airport while the Taliban tried to beat them back. Shirin did not make it to the airport that night; a Taliban fighter beat her with his gun. She returned home, desperately hoping for a miracle.

Half a world away, Rabbi Tzvi Boyarsky was sitting in his office at the Los Angeles branch of the Chabad-affiliated Aleph Institute. He was in a Zoom meeting with the directorship of an international NGO focused on women’s issues. Justice Susan Glazebrook, president of the International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ) and a judge on the New Zealand Supreme Court, was present as well. As a Chabad rabbi sporting a brown beard, Boyarsky might have felt out of place on the call if not for the fact that he is quite used to making these sorts of connections.

Rabbi Boyarsky is the director of Advocacy at the Aleph Institute, a Jewish non-profit organization founded in 1981 by Rabbi Sholom Ber Lipskar at the express direction of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson. Aleph serves the religious, educational, and spiritual needs of those trapped in institutions and, under Rabbi Lipskar’s leadership, it has provided critical support to countless families, at the moment when support was hardest to find. In the course of advocating for the civil and religious rights of those detained around the world, Rabbi Boyarsky has come into contact with countless officials and humanitarian organizations. This Zoom call was par for the course.

“My father is dead, and the Taliban killed him,” someone read from an email. It was a cry for help she’d received from the nineteen-year-old son of a former Afghan employee. He said it was only a matter of time before the Taliban would return for him and his four orphaned siblings. Boyarsky had grown up hearing stories of the Holocaust, and images of uniformed soldiers rounding up innocent civilians hit a raw nerve. When he left the meeting, his team began working on an escape plan for the young orphans.

As a group of Chabad rabbis, Aleph brought a unique perspective to the effort. “Of course, you might not be able to save everyone,” says Rabbi Levi Landa, who worked on the rescue effort. “But we had to do whatever we could. The Rebbe taught us that when we encounter a situation it is not mere coincidence, rather G-d orchestrated it that way for a reason.”

Aleph started looking at overland routes through Pakistan, but before they could act, they needed funding. “Aleph is blessed with an amazing network of truly caring individuals,” Landa says, “after we shared the orphans’ story with Gordon Caplan, a friend of ours, we didn’t even conclude before he challenged us, ‘How many people can we save?’”

Over the next few months, Mr. Caplan’s question would set an extraordinary series of events in motion. Rabbi Boyarsky was only too aware of how many people faced death at the hands of the Taliban. Through Aleph’s relationship with the IAWJ, he’d heard about the sad fate of Afghanistan’s female judges. IAWJ’s phone lines were ringing with countless phone calls, texts, and videos, begging for help. With funding secured, Boyarsky offered to help get as many female judges out as possible. Using Aleph’s experience dealing with tricky international negotiations, the two organizations began working hand in hand.

***

Meanwhile, in Vienna, Fazel Malek was getting desperate. Under the 2009 Afghan Allies Protection Act, he was legally entitled to a visa to the United States and had spent four years on the waiting list for approval. During his wait, he’d already earned several degrees in business management. He yearned to see his little daughter again, and since Kabul fell, he’d been phoning every humanitarian organization that might be able to get his family out. His family was in danger — his wife and daughter, his sister Hanifa and her husband, both former judges who had put Taliban fighters behind bars, and his parents.

He heard about Aleph’s burgeoning rescue effort through his sister but was skeptical. “Growing up as a Muslim, I heard a lot of things about Jews when I was growing up, and they weren’t nice things,” he says, “I never thought a Jewish organization would be willing to help me.” Still, he had crossed off the other names on his list, so he placed the call.

It wasn’t long before he was excitedly making calls to Afghanistan with good news. “There’s a flight!” Aleph had chartered a passenger jet, and it was set to fly from Mazar-i-Sharif Airport, seven hours north of Kabul.

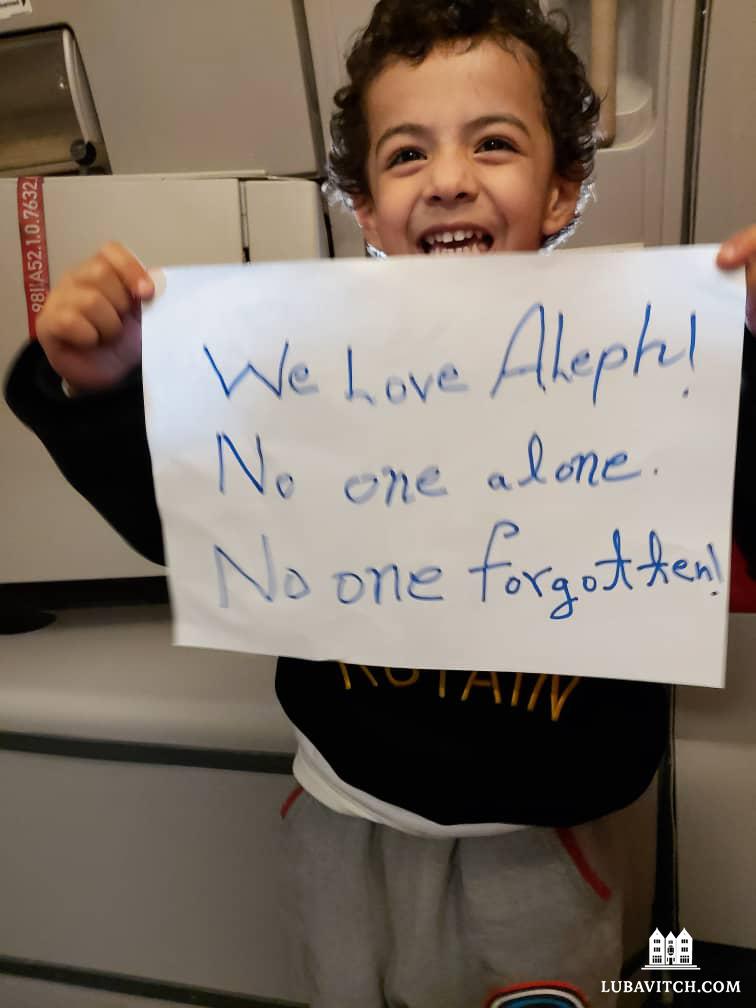

In October, Shirin Malek and her daughter crammed onto Aleph’s first flight to Abu Dhabi with three hundred and eighty other refugees. Children sat on their parent’s laps, and the baggage section overflowed with families’ entire worldly possessions. In a true logistical miracle, they had all arrived safely under the Taliban’s nose. As they left the runway behind, they sat in silence, fully aware that their challenges had only begun.

While his wife and daughter waited in Abu Dhabi, Fazel Malek began working with Aleph as a translator, helping rescue yet more people. On October 24th they arranged a second flight to the UAE, with Fazel’s sister’s family and his parents, the family of five young orphans, and another three hundred eighty people on board. Then, Fazel’s four-year limbo in Vienna suddenly ended when his United States visa was finally approved in January. With his fourteen-year-old son Hamid, he boarded a flight to New York and from there to California.

He quickly landed a job near Fremont, California, across the bay from San Francisco. Initially, he stayed with his old friend Paul in Petaluma, who he knew from his embassy days. But with no money to rent a place of his own and no car to commute to work, he was looking at a seven-hour daily commute to work by bus.

Malek mentioned his predicament to his Aleph Institute contact, Rabbi Yossi Charytan. “He was very anxious to get established in a place of his own before his wife and daughter joined him,” Charytan says. “I told him ‘hold on a minute, Chabad has somebody.’”

***

Rabbi Moshe Fuss and his wife Chaya moved to Fremont from Brooklyn ten years ago and opened up a small Chabad center in their home. “If you can create a Jewish community in Fremont, you can do it anywhere,” Moshe’s friends told him. In May 2021, the Fusses opened a permanent home for Chabad of Fremont, serving as the center of their vibrant community.

When Rabbi Charytan called up in mid-February and shared Malek’s story, Rabbi Fuss realized he could help. “Behind our center, we have a housing unit that we’d been using for our Hebrew School,” he says, “it wasn’t furnished properly, but our location was perfect for his needs.” Paul from Petaluma drove the father and son duo to see the apartment. It certainly wasn’t luxurious, but it would do, they agreed.

“The place just didn’t feel like a home,” Rabbi Fuss recalls, “we weren’t going to let them move in like that.” He reached out to his community and asked for anything that would help make the unit livable. “We needed all the basics,” he says, “from a refrigerator and stove to plates and pens.” Sure enough, community members started showing up with everything a home might need.

Even the electrician who volunteered to look at the lighting took one look at the industrial fluorescent lights and shook his head. “He ran to the store and came back with lamps and candles,” Rabbi Fuss chuckles. “Many of my friends here knew what Fazel was going through because they were in his position after they fled the Soviet Union,” Fuss says, “so they know how hard it is to get started from nothing.”

Fazel arrived on a Sunday night before his job began and was blown away. The bare unit had become a home. He and Hamid will make this their home for the next few months, though he is eager to get on his own two feet.

Although he spends most of his days at work, the community’s kindness has already deeply touched Fazel. “The Rabbi helped me get my son into school, and I met some very nice people in the community who insisted on driving me across town and are even trying to get me a car,” he says.

When Rabbi and Mrs. Fuss invited their guests to join them for a Shabbat meal, the Maleks were introduced to Jewish cuisine. “I told the Rabbi he tricked me,” Fazel laughs, “I thought the salad course was the entire meal.” Fazel even got to try gefilte fish for the first time, “it was like bread made out of fish,” he chuckles, “but it was very delicious.”

Most of all, Fazel says the kindness he’s received from the Jewish community has been a real eye-opener for him. “I’ll be honest, I never expected to find myself in a Jewish Center,” he says, “but the support these people have shown me is just incredible; these are very fine people.”

*Names of refugees changed for security sensitivities.